In some ways, Thailand is a fairytale of economic development. Thanks in large part to exports, its GDP per capita is now eight times what it was in 1980. Its people live 15 years longer than they did in 1970. They’re now better educated, so they are doing more high-value jobs. It’s also an exemplar of family planning; 80% of the reproducing population uses birth control, compared with just 15% in 1970.

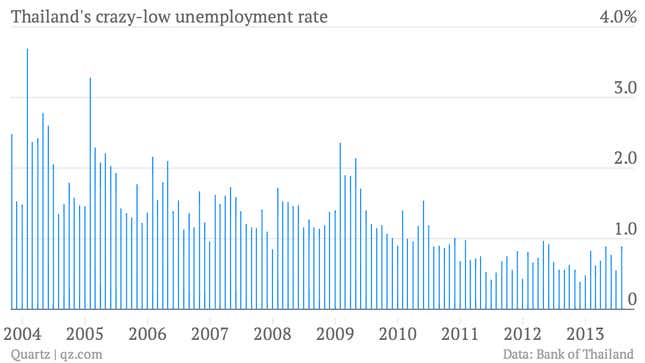

Which helps explain why Thailand’s unemployment rate is just 0.9%—the lowest among the world’s major economies.

But the upshot is that Thailand desperately needs cheap workers to keep growing. Thais are too educated and too few to do the menial jobs.

The solution? Migrants. And the cheapest of all are undocumented, trafficked and often forced laborers from Myanmar, and, to a lesser extent, Cambodia and Laos.

Thailand’s shrimp-peeling business is a classic example, as the Environmental Justice Foundation, a non-governmental organization, highlighted in a recent report (pdf). It’s a critical industry for Thailand, which typically produces one quarter of the 2.6 million or so tonnes (2.9 million tons) of the planet’s annual shrimp output. Some 90% of that goes abroad, making Thailand the world’s biggest exporter of shrimp. That brought in $3.5 billion in 2011, just shy of 1% of GDP.

Most of that shrimp enters importing markets already peeled, beheaded, deveined and gutted. But dismantling tiny crustaceans is laborious. The conditions in “peeling sheds,” reports the EJF, are noxious, the hours long, and the pay dreadful.

Unsurprisingly, Thais long since stopped taking those jobs. Migrants, mostly from Myanmar, can earn more there than they would at home, and thus send money to support their families. Though Thailand’s estimated 3 million migrants make up 10% of its workforce, in seafood processing, they compose 90%.

But protecting workers and punishing abuses is expensive. It also risks making Thailand’s exports pricier. Maybe that’s why the government does neither. The litany of abuses in peeling sheds includes trafficking, forced and child labor, debt bondage and sexual harassment, to name a few, reports the EJF. In Samut Sakhon, a major seafood processing center, 57% of workers surveyed had been subject to forced labor practices, while one-third had been trafficked.

Or perhaps it’s because some officials are complicit, taking bribes or even owning the businesses. EJF spoke with five former employees of a Thai police captain’s peeling shack. All been trafficked into debt bondage; one was 10 years old at the time.

It’s not just shrimp, though. Export competitiveness in fishing, construction, agriculture and manufacturing depends on migrants, says Human Rights Watch (pdf, p.25), an NGO.

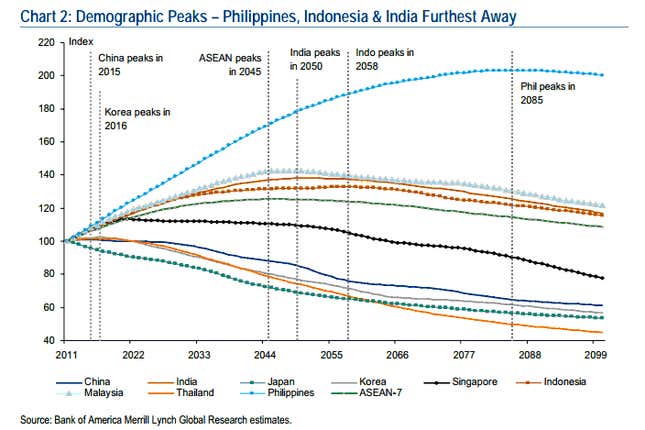

This might be expedient now. But Thailand’s labor productivity has stalled (pdf, p.3) because companies grown used to cheap labor aren’t bothering to upgrade their technology. The consequences of this easy fix will become more glaring as 2017, the year Thailand’s working population starts shrinking, approaches.

At that point, as the local population falls, demand for migrants should intensify. That will up their wages, crimping margins, or exacerbate trafficking, which could invite sanctions against Thai exports. And that’s assuming this captive labor pool doesn’t dry up first, as Myanmar’s rapidly liberalizing economy starts to pick up.

Which all means that, at some point soon, Thailand will find a crucial engine of growth sputtering.