The first chapter of Chinese urbanization was a story of migrant workers. The next chapter will be about their families.

As China continues to grow, rich, effective urbanization will require more than just providing job opportunities. It will require new policy initiatives to bring more children and elderly from the countryside into the city. By doing so, the Chinese government can begin to address Chinese income inequality, rebalance the economy toward services and consumption, all the while setting the stage for further economic reforms.

According to population data from the Chinese National Bureau of Statistics, over the past 30 years the proportion of Chinese people living in cities has more than doubled from around 20% to over 50%. Most of the migration into the cities has been in the form of migrant laborers leaving the countryside in search of higher wages.

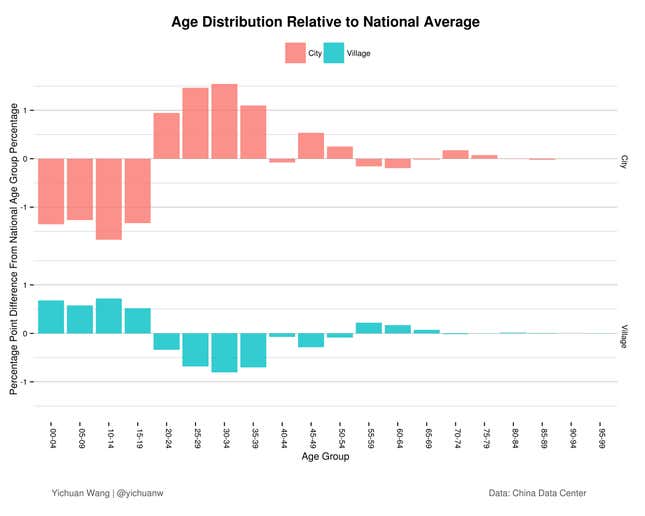

As a result, prime age laborers are overrepresented in the cities while children and the elderly are underrepresented. According to the 2009 population survey, the proportion of people in cities between the ages of 0-19 was about 2 percentage points lower than in the villages. This number was reversed for people between the ages of 20-39. When mothers and fathers move to the cities in search of higher wages, they leave their children behind to be taken care of by grandparents. As such, if urbanization is going to continue, it will need to bring these groups into the fold.

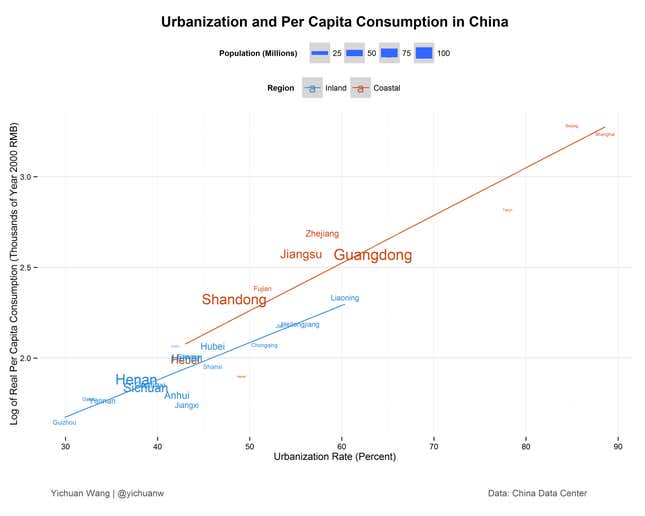

While migrant workers are unlikely to spend much on education or health care in the cities, these expenditures would quickly rise if the cities were filled with children and the elderly. As a result, more income would go toward consumption. On average, a 10 percentage point increase in a province’s urbanization rate is associated with an increase of 30% in per capita consumption expenditure. Empirical research in China has established that large population sizes are necessary to support service industries, so it is also likely that this connection between urbanization and consumption is causal. Moreover, because the service sector is much more labor intensive than manufacturing, rural laborers would still be able to find productive employment in the cities. This could spark a positive feedback loop that transitions China away from its current manufacturing and investment-centric model toward one based on services and consumption.

Urbanizing the young and the old would enable a much more effective social welfare policy. Consider the provision of health care services in rural China. While a system of “barefoot doctors” may have been sufficient in Mao’s time, it is no longer an option for an increasingly prosperous China. Although the urban health care system is becoming increasingly sophisticated, China still “struggles to provide basic care to large portions of the rural population.” In particular, it is very difficult to convince doctors to move to the countryside to deliver care. While certain brave souls may be willing to ride their bike “five days a week, under the scorching sun or in drenching rain” to visit patients tucked away in the corners of the countryside, it is unrealistic to expect that the Chinese health care system will be able to consistently deliver such services. Rather, a more efficient strategy would be to bring more of these rural residents into the cities, and to improve the quality of hospitals there.

While many critique the economic inequalities perpetuated by China’s current economic growth, it would be impossible to effectively address such inequalities with cash transfers unless China further urbanizes. This is because it is more difficult to provide the infrastructure and personnel for services in the rural backwater. Therefore, efforts made on this front have to come at the cost of growth elsewhere.

The same holds for education. It is much harder to build schools, maintain teachers, and hold onto students in rural environments. When China started consolidating and closing down rural schools in 2001, part of the reason was that there weren’t “enough teachers due to the harsh environment and low payment.” Data from the 2010 Chinese Population survey show that only 50% of rural Chinese have more than a middle school education, whereas the comparable number for urban Chinese is 80%. This problem will only get worse as China gets richer. As such, the only sustainable way to encourage education among the rural poor is to bring them to the cities.

This strategy may sound harsh, but pouring more money into creating a “new socialist countryside” is inefficient. There just aren’t enough productivity gains to be made in the countryside to justify such an investment. In addition, given a finite supply of total resources available, any money spent on expensive methods of delivering rural health care and education is money not spent on accommodating the rising urban class. On the other hand, by making social services in the cities more robust, the government can provide higher quality services and improve health and human capital.

To facilitate this new urban transition, Chinese provinces should take steps toward liberalizing access to urban social services for migrant workers and their families. Under the Chinese Hukou system, farmers who migrate to the cities are not entitled to the social welfare programs (pdf) that other urban dwellers receive. They do not have access to urban health insurance or old age pensions. Their children cannot attend the same public schools without paying exorbitant fees. By slowly changing these policies, the provinces could make family life in the city a possibility for migrant workers, and more of the children and elderly would come into the cities.

Guangdong has already taken steps toward (pdf) making this a reality. Since 2010, Guangdong has instituted a policy that allows migrant workers to enter their kids into the school system after five years of residence and eventually apply for Hukou registration after seven years. While there is a list of requirements for the parents, none involve high educational attainment or exceptional talent. Instead, they focus on making sure that the parent has paid taxes and has been a well-behaved citizen.

If this policy is successful, then the combination of more robust social programs and urbanization may lay the foundation for comprehensive Hukou reform. As discussed on a Shenzhen-based financial news television show Caijing (link in Chinese), the general consensus is that comprehensive Hukou reform is not possible at this time. There just aren’t enough resources to allow everybody to enjoy urban level social services. Moreover, the resulting mass migration into the cities would cause a sudden shock city that governments wouldn’t be able to cope with. But if provinces slowly equalize the treatment of migrant workers in social programs, then Chinese provinces could experiment and avoid the turbulence of radical reform.

Unless China can encourage more rural families to move into cities, growth will continue to be unequal and unbalanced. But if China is successful, the next chapter of urbanization holds the potential for closing the current rural/urban gap by allowing everybody to enjoy the benefits of the city. This change will likely reconfigure the growth model of the Chinese economy, and set the stage up for even broader reform.