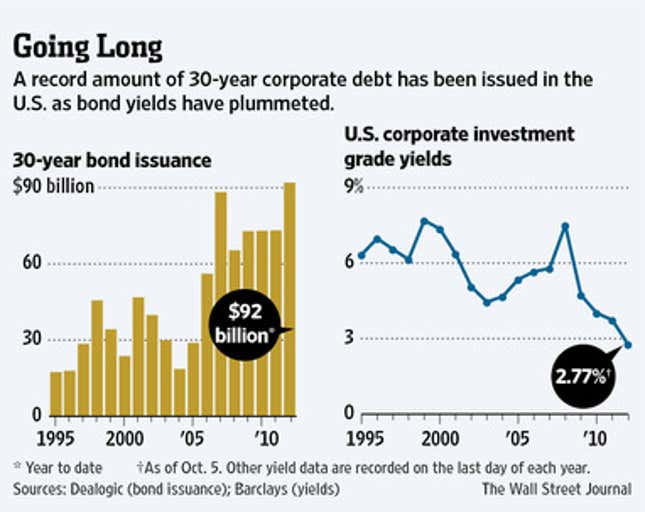

Companies are jumping on record low interest rates and borrowing tons by selling long-term debt in the US. The Wall Street Journal reports that sturdy companies—those rated investment grade—have sold more 30-year bonds (paywall) so far in 2012 than in any full-year period, going back to 1995.

Companies usually pay a higher interest rate to borrow for longer, to compensate investors for the higher risk of tying their money up for an extended period. That suits the investors, who get higher yields on the bonds they buy from the companies. And right now it suits the companies because, while borrowing for the long term does cost them more than for the short term, current interest rates are historically low.

In theory this should bode well for the economy. Much like homeowners, companies can use the current low rates to refinance outstanding loans. That cuts their cost of debt-servicing and—theoretically—frees up more cash to be invested in productive assets. In an economy with strong demand, cheap borrowing could also make some projects a better bet and may convince companies to go ahead with plans to expand.

Here’s the problem. US companies are already sitting on a ton of cash. And judging from some of the comments of the chief financial officers the Journal talked to, this year’s rash of long-term bond selling seems more defensive that expansive:

Among those tapping the market was United Parcel Service Inc. On Sept. 24, UPS refinanced $1.75 billion of five-year bonds coming due in January 2013 through a three-part bond deal, including $375 million of 30-year bonds that paid 3.625% annually.

The timing of the deal “was a combination of the current credit market and looking at avoiding fourth-quarter uncertainty,” said UPS spokeswoman Susan Rosenberg.

Ms. Rosenberg said that there was seven times the demand for the bonds than the amount available. She added that the company wanted to raise the funds ahead of any disruption to the economy caused by government negotiations over tax and spending cuts.

Indeed, US business has been looking increasingly jittery lately if the latest economic reports on US durable goods, nonresidential construction and factory orders are to be believed. Many have been pointing past the looming election to anxiety over a replay of last year’s disruptive US debt-ceiling debate as a reason companies are increasingly concerned. And of course, the overall weakness in the global economy isn’t helping much either.