China’s banks have been a bit short of cash lately. And there’s not a lot out there.

How do we know? When something is in demand, and there’s not enough, the price goes up. And we’ve been seeing the price of Chinese short-term loans stay stubbornly high. (Although they do tend to spike up around the annual Golden Week slowdown.)

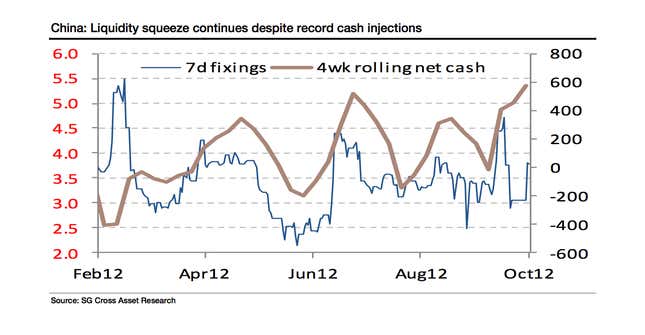

In fact, the People’s Bank of China (PBoC) pumped $42.14 billion in cash into the market to try to push the price of cash lower Oct. 9—the second-largest amount the central bank has ever injected into the money markets (i.e., the short-term lending markets) in a day. The largest ever cash dump was just a couple weeks ago. And even so, it seems short term interest rates still want to rise. Here’s a chart of the dynamic, from SocGen:

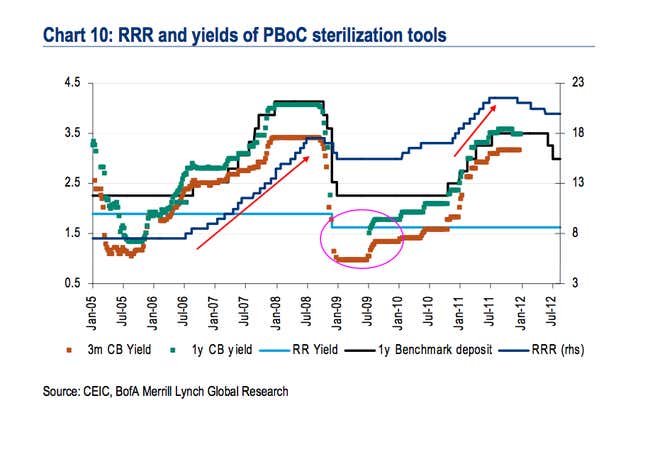

So what’s going on here? Reading the tea leaves of Chinese monetary policy is never easy. But analysts argue that the PBC is in the midst of a significant change in the tools it uses to tighten or loosen money. Like other central banks, during the worst of the financial crisis, the PBoC tried to make borrowing as cheap as possible to keep economic growth from going off a cliff. To do this, the bank cut its key benchmark rates, the lending and deposit rates. But it also cut the required reserve ratio (RRR), a measure of the capital banks have to have on hand, making it easier for them to lend.

Chinese banks got the message. Lending soared. But there were problems. For one thing, the surge of money in the system got inflation going. For another, a lot of the loans the banks made were of questionable quality. Such issues prompted the Chinese to tighten up lending conditions in late 2010 and early 2011. But still, there are concerns that Chinese banks may be sitting on a mountain of loans that are about to sour. (Their reporting on non-performing loans is notoriously unreliable.)

Now, as China’s economy is slowing, policy makers are again cutting rates. But they don’t want a repeat of this banking mess. So instead of chopping the RRR, the PBoC is this time using ”reverse repurchase” agreements, essentially very short-term loans, which inject money into the financial markets but don’t leave it lying around for too long.

But the PBoC might be forced to take bigger steps if it really wants to drive short-term rates lower. These cash injections aren’t really having the effect, as that first chart indicates, and as SocGen analysts argue:

“The purpose of [reverse repo] as a way to address short-term liquidity shortage seems to be overstretched at present given the persistent liquidity needs in the system. In other words, the liquidity issue is no longer a temporary but a permanent issue. The never-ending and increasing size [reverse repo] operation is not expected to be sustainable.”

To put it in a form that Goldilocks would understand: the first bowl of easing (cutting reserve requirements) was, in money-supply terms, too hot. The second bowl (reverse repos) was too cold. The PBoC has yet to find a bowl of easing that’s just the right temperature.