Any day now, a court in Luoyang, a city in the heart of Chinese mining country, will decide whether to imprison Kun Huang, a Canadian national who analyzed stocks for EOS Holdings, a Vancouver hedge fund. Huang was arrested in Beijing on December 2011, months after the fund published a report based on some of his research that alleged lower-than-reported silver content in ore from a mine run by Silvercorp, a Canada-based miner operating in Henan.

The local police say that 35-year-old Huang criminally defamed Silvercorp and took illegal videos of the company’s mine. Huang denies this. His defense lawyers produced evidence suggesting the police were in cahoots with Silvercorp, and of them admitting that they’d trump up charges if necessary, as Barron’s reports in its must-read exposé.

But Huang’s story isn’t unique. He’s one of hundreds detained in the last two years for conducting due diligence on companies’ China operations, particularly ones listed overseas, reports Barron’s. Needless to say, the threat that corporate bosses in league with police can imprison analysts they think have crossed them will make it much harder, riskier and expensive to research Chinese companies.

Silvercorp, which is based in Vancouver but operates in Henan, is listed in both Toronto and New York. The company’s website boasts that it is “a preferred mining company in the [sic] Henan province” and one of Luoyang’s biggest taxpayers. The company is led by several naturalized Canadian citizens of Chinese extraction.

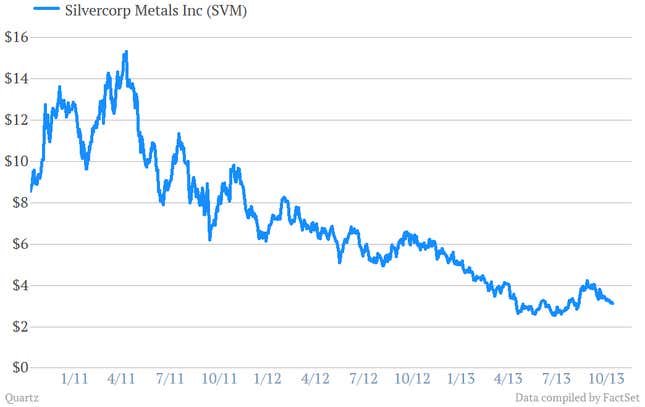

After EOS Holdings published its September 2011 report on Silvercorp’s ore quality, the Toronto-traded share price plunged 20% in just a day. It’s stock is currently down 58% since September 2011. The company has accused short-sellers like EOS of running a campaign against it, and brought a defamation case last year against EOS, which it lost.

EOS’s head, Jon Carnes, shared evidence with Barron’s that he says shows Silvercorp’s role in Huang’s arrest. Much of the evidence was compiled by Huang’s colleague Michael Wei, a Chinese national the Luoyang police arrested in December 2011, who later escaped to London. This includes Luoyang police travel expense documents allegedly paid by Silvercorp’s subsidiary, Henan Found Mining, as well as police booking records for Huang allegedly marked with the signature of a Silvercorp executive as a witness. In a defamation suit that Silvercorp filed in New York, Carnes also argued that an EOS contact list in Silvercorp’s possession could only have come from Huang’s laptop, which Chinese police seized (it featured the same typos and included Carnes’ personal frequent flier number).

But perhaps most alarming of all are statements made by Feng Yi, a Luoyang police officer, which Wei surreptitiously recorded. ”Now you messed with Silvercorp, and the issue is elevated. Now they have some central government leaders’ support,” Feng said, according to Barron’s, which examined the recordings. “So you just have to be punished… I’ll even fabricate a charge on you.”

Huang’s defense lawyers presented this evidence in the Luoyang court. They say that when asked to explain his recorded comments, Feng declined to respond. But Huang’s chances aren’t good. China’s conviction rates exceed 98%.

Barron’s says Silvercorp would not speak to it but has previously said that EOS must have forged the incriminating receipts.