The markets seem sanguine that wiser heads in the US Senate are going to prevail and make sure the US actually pays off the people it borrowed money from. Hard to believe achieving such a basic function of government is seen as a success, but here we are.

The rough outlines of the deal, as reported, suggest that it would raise the debt ceiling through early February and fund the government’s operations through mid-January. But we’ve still got a long way to go. Even if the deal passes the Senate, it then arrives at the Republican-dominated House of Representatives, where House Speaker John Boehner faces a politically sticky choice of alienating the extreme wing of his own party by bringing the Senate bill for a vote, or trying to negotiate further and risk being blamed for a potential catastrophic default.

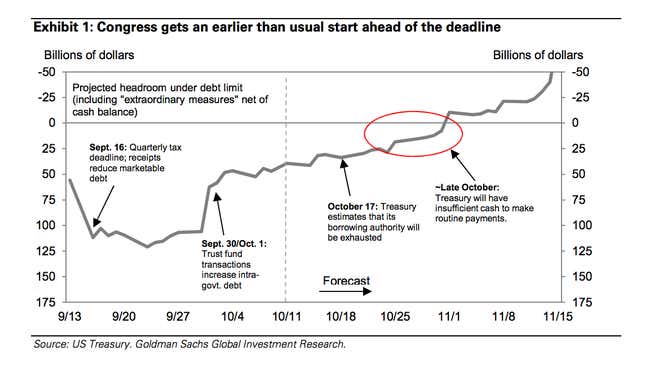

There isn’t much time left. The Treasury Department has said that by Thursday (Oct. 17) it will have reached the limits of the “extraordinary measures”—essentially an ongoing act of financial juggling—that allowed it to keep borrowing. And that means it will have to rely solely on revenue inflows—and a roughly $30 billion bank account—to meet its obligations.

The bottom line is: When will the US coffers run dry without a debt ceiling hike? No one knows exactly. But pretty much everybody says that the US will not have enough money to make more than $60 billion in payments on Nov. 1. Here are a few looks at the looming threat of default from Wall Street analysts.

Goldman Sachs:

“The current negotiations could carry on for several more days. In the meantime, the government seems likely to remain partially shut down. It is possible that the negotiations carry on slightly past the Treasury’s stated deadline of October 17. That said, in our view the progress made over the last few days signals that the risk of a worst-case outcome related to the debt limit, which we already saw as very low, is now even lower.”

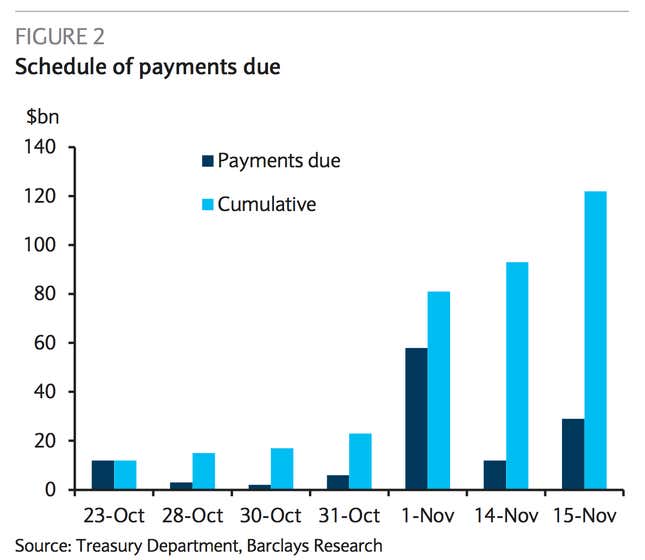

Barclays:

“Given the large block of payments due on November 1 (including Social Security, Medicare and military pay) this is perhaps the most likely day on which outgoings will exhaust all funding methods, absent a debt ceiling increase (Figure 2).”

JP Morgan:

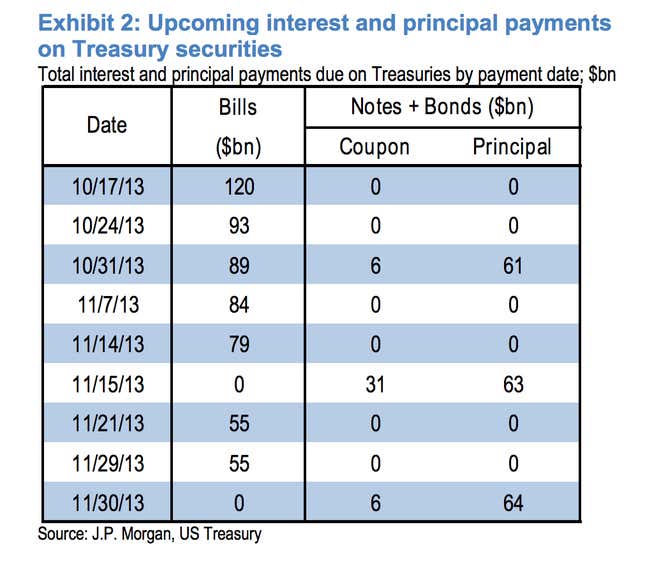

“Exhibit 2 summarizes the updated interest and principal payments (in $bn) due in the six-week period between mid-October and end-November (see Appendix 2 for a full list of securities). Considering November 1 as the “drop dead” date and assuming any technical default is short-lived, bills maturing in the late October/early November appear to be most at risk of being the first to default.”