Depending on who you ask, the UK’s Competition Commission either “diluted,” “rowed back“ or “wimped out“ in its attempt to reform the its regulation of the financial auditing industry this week.

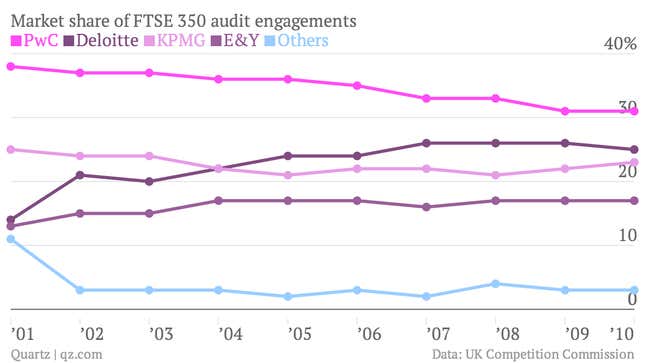

Britain isn’t alone in its inability to shake things up: The status quo in the audit world has barely budged for decades. When it comes to signing off on a major company’s financial statements, one of the “Big Four” firms—Deloitte, Ernst & Young, KPMG and PricewaterhouseCoopers—almost always gets the job. Firms outside of the Big Four audit only 15 of the UK’s 350 largest listed firms; all but two of the S&P 500 use a Big Four bookkeeper. Globally, the Big Four collect two-thirds of the accounting industry’s $165 billion in annual fees.

Enron’s accounting scandal brought down Arthur Andersen in 2002, but since then the Big Four firms have weathered the collapse of clients like Lehman Brothers along with plenty of other legal missteps that happened on their watch without suffering too much damage.

How long is too long?

Part of the problem, critics contend, is that companies tend to keep the same auditing firm for a long time, leading to overly cozy and complacent relations between auditor and auditee. The average auditor tenure at Fortune 100 firms is 27 years, according to Ernst & Young (pdf); Deloitte has been Procter & Gamble’s auditor since 1890.

Certain institutional investors now make it a policy (pdf) to vote against auditor re-appointments that exceed a certain period of time, but broader changes are unlikely unless regulators get involved.

The UK competition watchdog just wrapped up a mammoth two-year investigation into the audit market with a 327-page final report. (Is anything about accounting ever simple?) The key recommendation, which generated the derisive headlines, is that large listed firms will be required to re-tender their audit contract every ten years. Previous proposals suggested a five-year tender requirement.

Backtracking on audit reforms is something of a global theme. The EU is now debating the mandatory switching of auditors after 15-20 years, instead of 6-9 years in draft proposals, and the US recently nixed a plan to require rotation.

Let’s ask the clients

Audit firms, investors, regulators and politicians have been prominent players in the debate about auditor rotation. But what do the companies being audited think? Quartz contacted current and former CFOs to find out. Given the sensitivity of the relationships with their auditors, some declined comment. Others were willing to speak anonymously about the pressure to appoint a Big Four firm, what they got out of it, and the changes that are on the horizon.

CFO #1: The start-up specialist looking for value

“The basic product of an audit is pretty indistinguishable,” says a former finance chief of listed companies who now works as an interim CFO for fast-growing firms. “There is no differentiation” between the services offered by the Big Four, he adds, and ten years is too long of a period for an auditor to work with a given client.

The rise of class-action lawsuits targeting auditors is one reason to hire only the biggest firms, he adds, lest you are left in the lurch when a smaller auditor can’t shoulder hefty legal costs. In general, however, “you get a much more intimate service and more value from the people at smaller firms,” he says. The Big Four, on the other hand, dispatch armies of junior staff, and “what you’re paying for is the brand and the partner’s salary”.

At the smaller, privately-held companies he works with, he never considers hiring a Big Four auditor because “it isn’t worth the fees they charge.” The Big Four is sometimes forced upon him, however, if his company is seeking big investments, loans or wants to be acquired by a listed firm. It’s worth noting that the UK’s latest reforms prohibit loan agreements in which the creditor requires that borrower use a Big Four auditor.

CFO #2: The board member who is open to change, eventually

“It is not a trivial change to move from one audit firm to another,” warns the former finance chief of a large listed company who now serves as a non-executive director on several boards. What’s more, the big institutions that companies deal with—investors, banks, ratings agencies and the like—see a Big Four auditor as shorthand for “assurance and confidence” in the integrity of a company’s accounts. The same Big Four firm audits all of the companies where he is a director.

There are ways to keep things fresh, even if a company keeps the same Big Four auditor for a long time. If a company rotates the lead audit partner every three years—which “brings some new perspective without incurring the costs of changing firms completely”, he says—a ten-year engagement with a firm is palatable. Even so, waiting ten years to re-tender an audit contract is far too long, he says. “For any other service you buy, the board would be uncomfortable not testing the market more frequently.”

In his experience, ”the gene pool is pretty much the same” at top and mid-tier audit firms, with a similar quality of service as a result. Although he thinks the changes proposed by the UK regulator are “a start” in fostering more competition, he doesn’t expect major changes any time soon. Why? In part, it is an awkward “chicken and egg” problem, he says. “If one reasonably large organization has the confidence and courage to [appoint an auditor outside of the Big Four], change will come gradually. It just needs a few breakthroughs.”

CFO #3: The finance chief who wants a fresh view at a good price

“If you are a big company nowadays you have to show that one of these four is signing off your financial statements,” the European CFO of a US-listed firm says bluntly. His company did, however, recently sever a decades-long relationship with one of the Big Four in favor of another. “The change was overdue,” he says. “It was time to bring in a new, independent perspective.”

The impact was immediate. “We’re getting more added value right from the start—there is more dialogue and more meetings,” he says. “And we are paying less.” One way his firm cut the bill is by farming out low-level local statutory audit work in selected countries to a mid-tier audit firm; the Big Four group auditor incorporates this work into its overall assessments. This, more than anything else, hints at a possible challenge to the Big Four’s dominance. CFOs love nothing more than driving a hard bargain with suppliers, particularly if they aren’t satisfied with the quality on offer.

By doing his part to share audit fees outside of the Big Four, “hopefully in a few years we will be talking about a Big Eight or Big 12 or something like that,” he says. “It seems unreal that only four firms dominate. It’s like telling the world that from now on there will only be four big banks.”