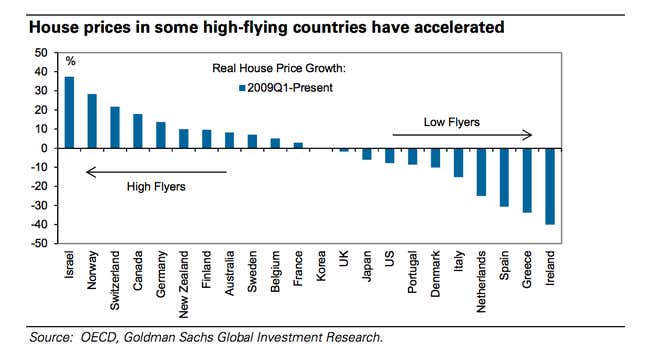

Goldman Sachs analysts spotlighted some of the world’s fast accelerating housing markets this week, in a bid to try to sniff out potential for problems in the making. (After all, it was the high-flying US housing market that served as the epicenter for the financial crisis that set off the Great Recession.)

Here’s a quick rundown on what’s been happening in some of the hottest housing markets in the world.

Israel

Since the depths of the Great Recession home prices in Israel are up roughly 40%. And the inability of young couples to get a foothold on the “housing ladder” has become an increasingly politicized issue. (The bubble helped elevate domestic issues and place them at least on equal footing with the perennial security problems in January’s general election.) Some policy tweaks are in the offing, including plans to close a tax loophole that has made owning Israeli apartments an enticing proposition for global investors in search of yield. That’s pulled in global capital and pushed prices higher. But of course the real issue is supply. A panel on Israeli socioeconomic change—formed in the wake of mass cost-of-living protests in Israel a couple years back—urged the construction of 200,000 new apartments over the next few years. But given Israel’s geographic constraints, and ongoing tensions over construction in Palestinian territories, it’s not obvious where these housing units would go.

Norway

With prices up roughly 30% since the worst of the Global Recession, Norway has pulled far ahead of even its strong Nordic neighbors in terms of housing prices. The rise is due, in part, to surging incomes and population thanks to immigration. Supply is tight because of land use restrictions and relatively stringent minimum size and quality standards. But the ongoing surge in prices is making some a bit jittery. Household debt in Norway is high, and much consumer wealth is locked into illiquid real estate. So, a downturn in the housing market could result in some sharp cutbacks in consumption. And while the oil-rich nation has weathered the recent global economic slowdown almost effortlessly, it had its own nasty financial crisis in 1987 tied to over-exuberance from a recently deregulated banking system.

Switzerland

Historically low interest rates and a flood of cash into the Alpine banking bastion have driven housing prices up more than 20% since the the first quarter of 2009, according to Goldman. Mortgage debt surged to 140% of GDP, high both for Switzerland historically and compared to other nations. Some nascent efforts to tighten up lending standards have been tried, including efforts to force banks to set aside more capital in case its stockpiles of mortgages start to sour. But so far none have slowed the boom. Goldman analysts see Switzerland—along with Germany and Israel—as one of the national housing markets with the largest risk of a sharp decline in prices over the next few years. (It puts the odds of such a decline at around 30%.)

Canada

With real home price appreciation near 20%, Canada’s home price growth has been raising eyebrows. Bank of Canada governor Stephen Poloz doesn’t see a bubble, but others aren’t so sure. Climbing alongside housing prices have been levels of household debt, which surmounted 165% of income in the second quarter of 2013. (That’s not too far from where they were in the US before it suffered its housing crisis.) And the Bank of Canada itself has even warned about risks posed by frothy condo sectors in big cities like Toronto. A few hedge funds, such as San Francisco-based Hyphen Partners, have even made high-profile bets on a Canadian housing bust. They haven’t paid off, yet.

Germany

Nearly half of all Germans rent, which makes the nation a somewhat odd candidate for a housing bubble. But there are signs that officials are concerned about puckish surges in housing prices. In its October monthly bulletin the Bundesbank warned that prices of apartments in cities such as Berlin, Hamburg and Munich were as much as 20% higher than economic fundamentals could justify. An analyst who spoke to the Wall Street Journal said apartment prices in Berlin are up some 80% between 2009 and 2012 (paywall). Observers blame an inflow of international capital for the price jumps. Investors have used low interest rates to invest in homes in Germany, a bastion of economic stability within the eurozone. Goldman Sachs analysts point out, however, that overall “given that house prices are just coming off a low base, national house prices are unlikely to be significantly overvalued at this point.”