By a single vote, Greenland’s parliament passed a measure to overturn a 25-year ban on uranium mining. Hours of “heated debate“ in the country’s icy capital, Nuuk, reflected the depth of feeling about the issue.

Greenland is self-governing, but its defense and foreign affairs are shared with former colonial ruler Denmark. The ban on uranium mining stems from Denmark’s anti-nuclear stance; the country—home of atomic pioneer Niels Bohr—prohibited the production of nuclear power in the 1980s. Access to Greenland’s uranium resources will be a boon to energy-intensive, atom-splitting economies like China, which is already keen on the island’s other resources. A massive iron-ore project—worth more than Greenland’s entire annual GDP—was announced yesterday by a UK-based company that plans on importing Chinese labor to work the mine.

The real prize, however, is what’s mixed up with Greenland’s uranium. Rare earth metals, the scarce and expensive elements crucial for batteries, smartphone components, medical devices and other advanced electronics, are thought to reside in huge quantities amidst the island’s main uranium deposits. By lifting the ban on digging up radioactive minerals, Greenland will unlock its sizeable stores of rare earths as well. Climate change is also “helping” in this regard, melting the glaciers that cover much of the mineral-rich island. (At the same time, the shifting climate is savaging Greenland’s fishing industry, which is currently its largest source of exports.)

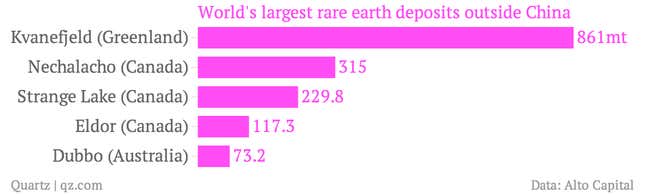

The EU reckons Greenland is sitting on 9% of the world’s rare earth resources, most of which are located in the massive Kvanefjeld deposit, which is run by an Australian firm. China currently accounts for nearly all of global rare earth production, and consumes more than half of world supply, so it is understandably interested in the thaw—both literally and figuratively—in access to Greenland’s rare earth resources. This makes other countries that rely on rare earths nervous, given China’s tendency to play politics with its rare earths supply. Nuuk can expect a boom in visiting diplomats keen to gain favored access to non-Chinese rare earths.

Greenlandic prime minister Aleqa Hammond is wary of getting “ripped off“ by the foreign players who are already scouring the country’s mineral deposits, and will surely redouble their efforts now that the uranium ban is lifted. But after taking over in March this year, she is keen on signing new mining deals in order to reduce the island’s economic reliance on fishing and subsidies from Denmark. “Before our contact with the outside world was based on whales and seals and what we ate,” Hammond told reporters shortly after taking over. “Today, it’s based on minerals and the consequences of climate change.”