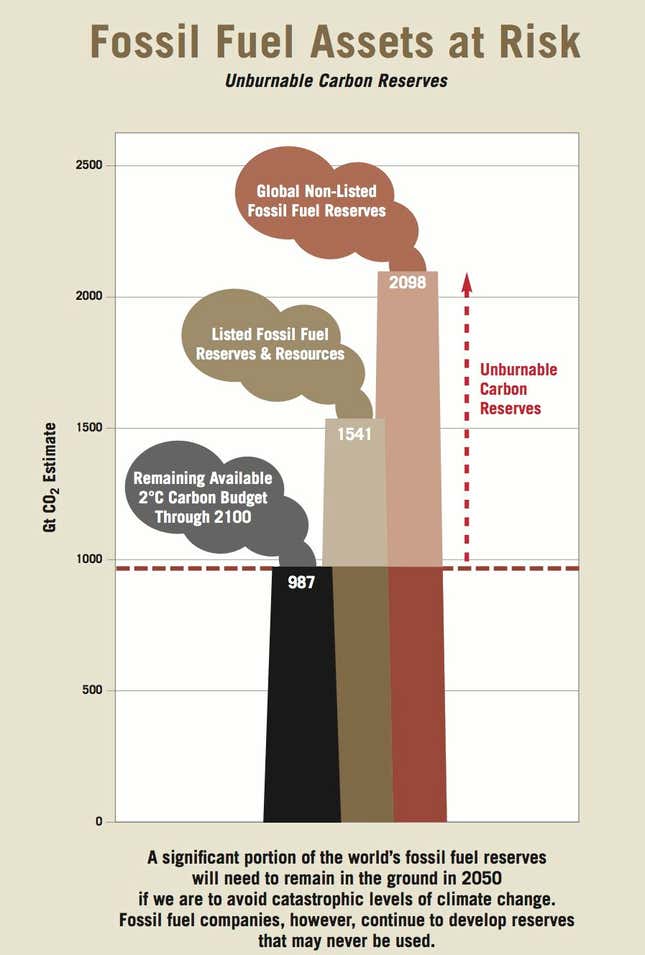

The International Energy Agency last year warned that if humanity is to have any hope of avoiding catastrophic climate change, a third of the world’s fossil fuel reserves must be put off limits until 2050. That prompted HSBC Global Research to estimate that some oil giants could lose up to half their market value. In other words, we’re talking about trillions of dollars in revenues going up in smoke if governments ever get their act together and issue a no-burn order.

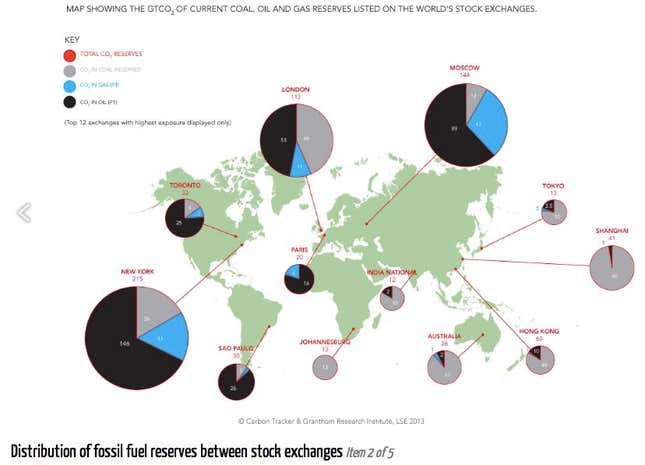

Now 70 investors that control $3 trillion in global assets want to know what 45 multinational oil, coal and mining companies intend to do about $6 trillion in potentially “stranded assets.” In particular, the investors—mainly public pension funds like the California Public Employees Retirement System (CalPERS) —are pressing the companies about their plans for future capital expenditures, given the high cost of exploiting new reserves and the risk that carbon taxes or other emissions limits could depress demand for fossil fuels.

“It is therefore important to understand how current and probable future policies to make these emissions reductions will impact capital expenditures and current assets in the oil and gas sector and how the physical impacts of unmitigated climate change will impact the sector’s operations,” the investors wrote in a letter to top BP executives that was released yesterday.

“We have a fiduciary duty to ensure that companies we invest in are fully addressing the risks that climate change poses,” said Anne Stausboll, chief executive of CalPERS, said in a statement. “We cannot invest in a climate catastrophe.” CalPERS, the US’s largest pension fund, controls $265 billion in assets.

The campaign is being managed by Ceres, a Boston-based non-profit that promotes corporate sustainability. Andrew Logan, the director of Ceres’s oil and gas insurance programs, told Quartz the investors don’t expect fossil fuel giants like Chevron and Rio Tinto to transform themselves into renewable energy companies. “In the nearer term we’re aiming to place carbon asset risk on the agenda of the mainstream financial industry,” he says. “Longer term or even in the medium term, we do have expectations that we can impact the behavior of the fossil fuel industry and the way they invest capital.”

The HSBC report concluded, for instance, that 25% of BP’s oil and gas reserves were at risk from being declared “unburnable.” But those reserves only represent 6% of BP’s market value as they’re considered low-value.

Those reserves will only be put at risk, of course, if governments ever impose emissions limits or take other measures to restrict the burning of fossil fuels. But there are bigger entities than global behemoths like BHP Billiton that investors will need to sway. As the HBSC report noted, 90% of the world’s fossil fuel reserves are controlled by governments or state-owned companies.