Should Mitt Romney manage to collect 270 electoral votes in November and win the White House, he will have achieved something novel. Yes, he will be the first Mormon to win the presidency. He will also be the first corporate CEO to have successfully gained the most powerful office in the land. As an unabashedly data-driven, even data-fixated, man, his ascendancy to the post would also be a new high water mark for a new group rising to the top of US and probably global culture. Romney would be the first presidential representative from the Computational Class.

In his 2002 book “The Rise of the Creative Class,” urban theorist Richard Florida described what he believed was “the emergence of a new social class,” of roughly 40 million Americans who, while they didn’t necessarily see themselves as a distinct social group, could be defined by common interests and characteristics—“creative” as in conceiving and making. His Creative Class came not only from the fields that immediately spring to mind—music, design, art, entertainment—but from a broader set of occupations and disciplines: fields such as science and engineering, law and finance. The common thread Florida saw was that these professions and pursuits have a common creative thread, where human decision-making and insight drive innovation. This class even has a definable geography: the Northeast Corridor, San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Seattle, as well as smaller, more relaxed locales with good quality of life, like Boulder, Santa Fe and Austin.

Florida’s Creative Class took shape in a world where democratized technology and a strong economic tailwind were important enablers. As a result, technology emerged as something to “make” with, a desktop tool for deeper synthesis and personal expression. The Creative Class wields enhanced combinatorial capabilities to bring the “new” into being, only more and better than the Industrial Age, without a factory or foundry, but from home or an office on Main Street.

This description sounds familiar because it summarizes the boom of the 1990s and early 2000s and the path this boom set many of us on even as we entered the dotcom bust, recession and near-cratering of the economy we’ve experienced since then. With ever-evolving tools of conception and creation at their fingertips, today’s young Millennial workers, families and businesspeople, even as negatively impacted as they have been by the weak economy, still have those Creative Class genes, Masters of the Universe with shiny digital devices. The Creative Class didn’t go away, it just changed moods along with the rest of the economy.

In the meantime, two major trends have converged to alter the landscape. First, the cost of technology—computing, storage and communication—have fallen dramatically over the past decade, allowing individuals and companies in 2012 to leverage on a single desktop or in a server rack the kind of power that would have filled a room and cost millions of dollars in 1990. For example. the cost per gigabyte of storage was around $10,000 in 1990, but today is easily below $0.10. Computing power has gotten cheaper as well, following the famous Moore’s Law curve expressed by Intel’s Gordon Moore in the 1960s to describe the staggering evolution of semiconductors—smarter and smaller all the time. Similar economics have impacted bandwidth, getting more affordable even as network speeds increase. In short, we now have much bigger, faster, more powerful computational hammers to swing at problems for a fraction of the cost. As a result, everything from aircraft design to genome sequencing to stock trading has accelerated in speed and capacity as the cost of the computational tools necessary to do this work has fallen dramatically.

It might seem odd, that we should see such dramatic progress in technology development at the same moment that the global economy, and the US economy in particular, was melting. While it’s somewhat of a chicken-and-egg problem to try to untie whether technology growth was a driving factor in, or a beneficiary of, this economic weakening, the availability of such low cost, high impact technology certainly sharpened corporate focus on the additional profitability these developments could yield. We live in a time when every additional cent, driven by a tiny bump in reaction time, decision point, or decimal carried can be the difference between success and failure, between a big financial gain and a devastating loss. As the economic storm clouds gathered, technology transitioned from being a tool of peaceful creativity to becoming weaponized in the service of economic competition, enabling a smaller number of actors to yield greater economic growth out of far fewer resources—a new system of programmable money making.

The Age of the Algorithm

This is where Big Data enters, stage right. From the 1990s with the computerization of business, the godsend to data collection that is the internet plus falling costs and increasing computational power the world has been enabled to take giant leaps in data generation and collection. A recent calculation done by technology analysts IDC suggested that by the end of 2012, we will have generated nearly 2.5 zettabytes, or 2.5 trillion gigabytes, of data, from an increasingly digitized array of our daily personal and business activities. By 2020, IDC forecasts this data boom will increase the volume of data centers 50-fold, as a growing army of data jockeys seek to capture, compile and wring value out of the by-then 35 zettabytes of information of data exhaust we collectively create—200+ million e-mails, 100,000 tweets, almost 700,000 bits of personal info shared on Facebook, and 2 million Google queries per minute estimated in 2012 alone.

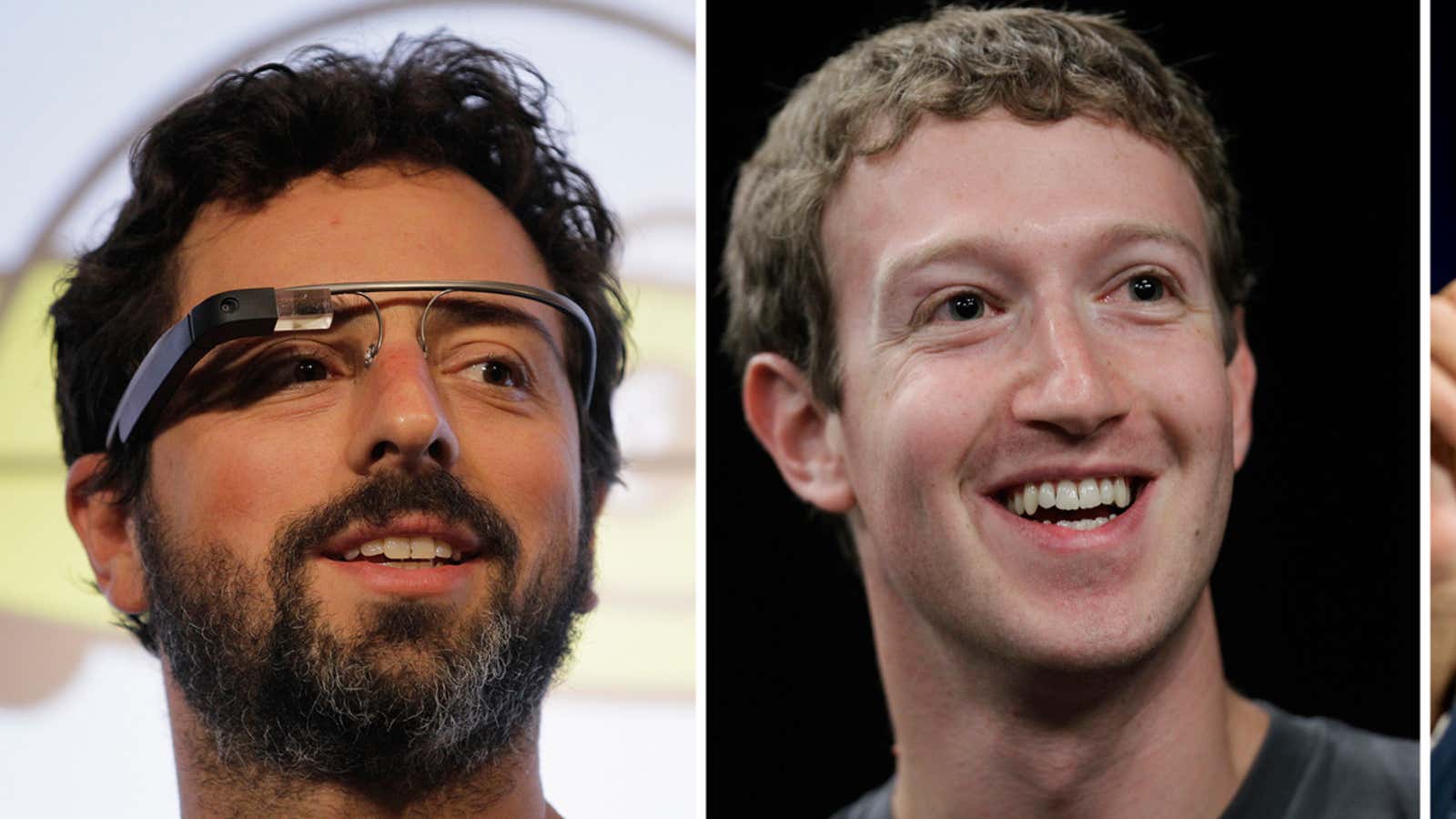

These data jockeys, big and small, increasingly look to be the inheritors of this Big Data-driven age. Data is becoming “the new oil,” as the new meme goes. The then-young pioneers of the early Internet era reduced people to “eyeballs,” setting in motion a sprint by many data-centric companies to monetize those valuable eyeballs. These were the beginnings of what has become the Computational Class, delivering us to today’s new data-driven moguls, the Zuckerbergs, Bezoses, Brins and Pages. Whatever services or content we think we are using on the front end, we are more accurately feeding a data beast behind the scenes—making it smarter and quicker as we lap up cheap or free services on our desktop, iPad or mobile.

Having cut his teeth at quant firm DE Shaw, Jeff Bezos, always envisioned Amazon as a data play. Amazon, besides being a bookstore, is forecasted to make an estimated $1 billion providing cloud computing services to other companies in 2012. While it’s known to its daily users as a search services company, Sergei Brin and Larry Page in effect built Google to be a giant learning tool—their algorithm made nearly $40 billion last year, trading on what it has gleaned about the world based on our behaviors and requests. Facebook made almost $4 billion last year off what it knows about who you know—monetizing friendships and reducing human interaction to a cash-generating “social graph.” The big money for the Computation Class is made off of trading data, manufactured by both man and machine, at as high a volume, as fast as possible, with a tight competitive edge in how that data is parsed.

A stark, but less high profile, illustration is how the Computational Class has harnessed (or not) the algorithm to mint money on Wall Street and in other financial capitals. High-frequency trading, executed by algorithms tucked on servers at major nodes on global networks and within the exchanges themselves are executing infinitesimal financial trades—and just as often head fakes to flush out market competitors—at a rate that have stealthily eaten large parts of global financial trading. A recent Morgan Stanley report estimated that almost 85% of all stock trading volume in the US is carried out by computers, not humans sitting at a trading desk somewhere on Wall Street or Chicago (other than to set a formula in motion). This is up to 70% from 50% the year before, according to the bank. In the UK, estimates put similar activity at 77%. Hiccups in these real and fake trades are blamed for creating ever larger flash crashes in recent years (the $440 million loss that rocked Knight Capital in August cost the firm the equivalent of 10% of Facebook’s 2011 earnings in just one morning). Daily high-frequency trade volumes are thought to be around $4 trillion, but even this is difficult to track as much of the activity takes place in so-called “dark pools.” And these aren’t just a tool for Wall Street: even buyers and sellers on sites as pedestrian as Amazon itself are getting into the algorithmic trading act.

Just as the Creative Class has a discernible geography, so does the Computational Class. As technologist Kevin Slavin illustrated in a TED talk from 2011, those harnessing the numbers for enormous gain are literally moving earth in the name of computational efficiency. The Robber Barons had railroads and oil, but the Computational Class has undersea cables and sub-arctic data centers. Previous generations had centers of manufacturing and centers of creativity, and the Computational Class has its own centers of calculation, in predictable places like Silicon Valley, but also cities like St. Louis and Toronto, and suburbs like McLean, Va., where data scientists have flocked to a combination of network nodes and highly computational businesses, like security, finance and biosciences. These places are formed by bandwidth underground, brains above.

Even though, like the Industrial Age, it has its own growing class of computational “barons” running data platforms and quant houses, the computational working class is booming as well. As manufacturing has declined, and the creative industries that were supposed to replace them have been hit by the recession, the life-or-death financial advantage that can be wrung out of data has created a leap in demand for data jockeys, “algo-wranglers” and others to feed the data beast. Going back to 2009, website Simplyhired.com indicates the number of job openings mentioning “algorithm” that it has collected from hundreds of employment sites has skyrocketed 228,713%, while for “big data,” the increase has been 37,489%, and those mentioning “high frequency trading” have grown by 35,561%.

For an area like Big Data that has only been formally described for just over a decade, its expansion throughout the economy has been astounding. Even if you aren’t working directly in these fields, the formulae will increasingly be working you, not just on Facebook, Google and Amazon, but getting a job, applying for a credit card or just trying to relax and watch a movie. If you have skills in this field, you have slightly better chances of being able to succeed at these activities: While pay in other sectors may be eroding, median wages for data scientists are doing quite well. In the US, the Bureau of Labor Statistics pegs median annual pay for what it calls “Computer and Information Research Scientists” at $100,660, versus an average of $73,100 for other computer occupations, and $33,840 for all US full-time occupations.

Mitt Romney’s world of data, pouring over computer financials, print-outs of employee benefits and voter demographics, seems a quaint anachronism compared to stalking millisecond trading patterns with names the Boston Shuffler and The Knife, or building “elastic clouds” like Amazon or patenting genes. Mitt made his money fairly slowly and methodically by comparison to the Silicon Valley generation, and yet it has taken him to within shouting distance of the Oval Office at least. The good old days of making money selling packages of software or even financial terminals, as Bill Gates and Mike Bloomberg did, already seems like your grandfather’s technology business. In 2012, we are already in the second phase of the Computational Class’s growth, where both processing and power grow exponentially. Whatever you search, click, buy, or locate feeds that data beast, and grows the pie for the Computational Class around you. And the math is on their side.