Child pregnancy is serious global problem, and in some developing countries it’s only getting worse, according to a new report released by the United Nations on Wednesday (Oct. 30).

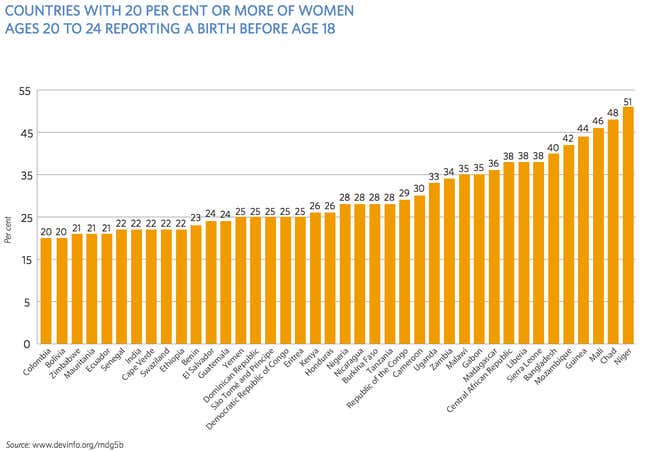

The UN’s annual State of the World Population for 2013, titled Motherhood in Childhood (pdf), highlights a number of stark realities in developing countries. Perhaps the most troubling are the alarmingly high rates of adolescent pregnancy still prevalent in many countries. As of 2010, over 36 million—or 19%—of women in their early 20s reported having given birth before the age of 18 (defined in the report as adolescent pregnancy). In West and Central Africa, the world’s two worst regions in this regard, the number was nearly 30%. Of the 54 developing countries surveyed by the UN, 15 reported a high prevalence—30% or greater—of adolescent pregnancy. Over 95% of the 13 million births to girls under the age of 18 occur in developing countries.

Perhaps more alarming is the rate of child pregnancy (defined in the study as births before the age of 15) in some countries. In West and Central Africa, 6% of reported births came before the age of 15. Bangladesh, Chad, Guinea, Mali, Mozambique and Niger fared particularly badly; one out of every 10 girls has a child before the age of 15 in those countries.

Part of the problem is that women in developing countries are getting married too young. Adolescent birth rates are highest in countries where young marriages are most prevalent. “Despite near-universal commitments [in these countries] to end child marriage, one in three girls in developing countries (not including China) is married before age 18,” says the report. Over 10% of girls in developing countries are currently forced into marriage before their 15th birthday. In Bangladesh, Chad and Niger, the number is over 33% (p. 24).

Marrying older men was also associated with having babies younger; the study found that girls who married men who were at least 5 years older were far more likely to give birth in adolescence.

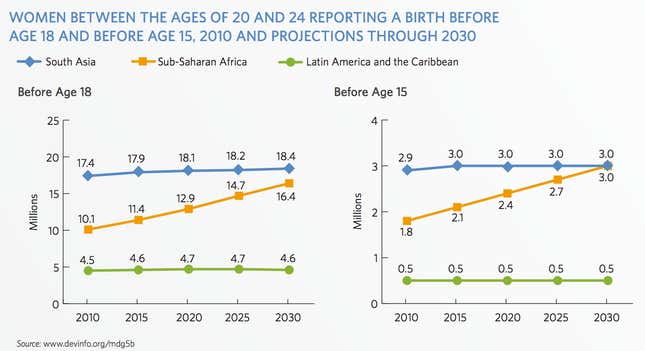

In some regions of the world, the problems of young motherhood are only getting worse. In Latin America and the Caribbean, births to girls under age 15 are projected to rise through 2030; and in sub-Saharan Africa, where such births are growing fastest, the number is slated to almost double in the next 17 years, according to the report (p. 19).

The health and economic implications are grim. Not only do adolescent births jeopardize the wellbeing of children born to unready mothers; they keep young women from working. Adolescent girls who marry and give birth at a young age are far less likely finish their education and, later, contribute to the labor force.