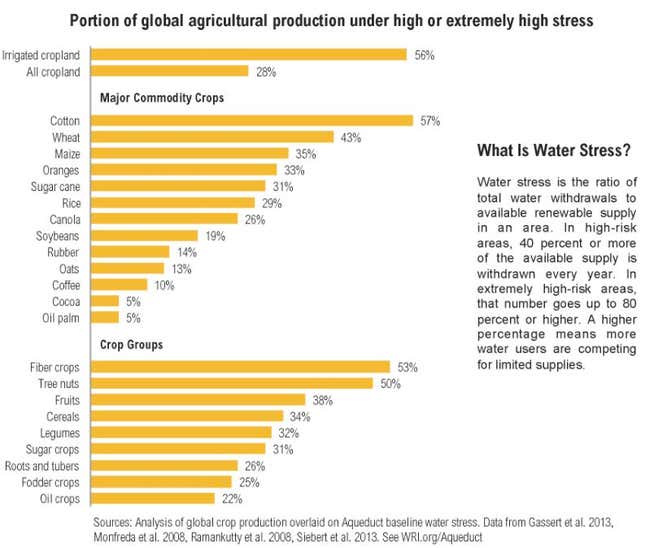

A quarter of the world’s food crops are now being grown in regions that are highly water-stressed, according to a report released yesterday by the nonprofit World Resources Institute (WRI). It gets worse: Half the planet’s irrigated cropland, which produce 40% of the global food supply, is located in areas facing severe water shortages as climate change exacerbates drought.

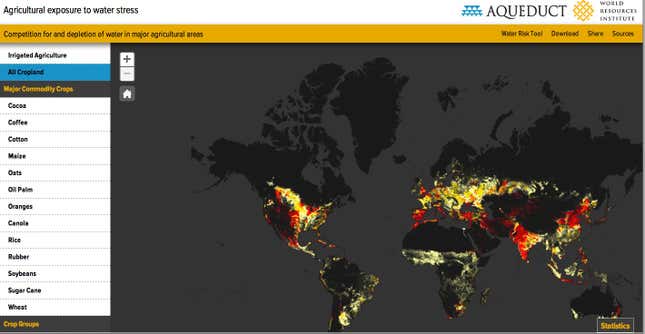

Tapping data from the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization and academic studies, WRI researchers overlaid food production with water resources to create an online interactive map that shows where the most water-stressed crops are grown. The WRI defines high water stress as areas where 40% of the renewable water supply is withdrawn annually. In extremely high water stress regions, 80% of the water supply is tapped each year.

For instance, 43% of the world’s wheat crop is raised in areas afflicted by high or extremely high water shortages, according to the WRI. Other staples of the global diet face similar stress: 35% of the maize crop and 29% of the rice crop are competing with fast-growing cities for water. (Waking up and smelling the coffee will get harder too in the years ahead: currently 10% of the coffee crop is grown in areas with declining water supplies.) Crops like carrots, beets and potatoes consume an average 0.5 liters (.1 gallon) of water per calorie produced. But lentils and beans need 1.2 liters (.3 gallons) for each calorie.

And it’s not just about the food on your plate but the clothes on your back. About 57% of the global crop of cotton—a particularly thirsty plant—is raised in water-stressed regions.

Agriculture currently accounts for 70% of the world’s water use and the WRI predicts water demand will jump 50% by 2030 while food production must increase 69% by 2050 to feed a global population that is estimated to reach 9.6 billion. “Agriculture’s growing thirst will squeeze water availability for municipal use, energy production, and manufacturing,” the WRI states. “With increasing demand in all sectors, some regions of the world, such as northern China, are already scrambling to find enough water to run their economies.”

As we’ve written, 85% of China’s electricity generating capacity is located in water-stressed regions. And China’s attempts to lessen reliance on coal-fired power plants and clean up the severe pollution they cause could only make the problem even worse.

So what is to be done? The WRI says part of the solution is increasing crop yields and switching to foods that can be grown more sustainably. Reducing reliance on heavily irrigated monoculture crops will also help, as irrigation is one of the biggest factors in the draining of renewable water supplies.