Things looked grim for America in 2006. Oil production was in steep decline and natural gas was nearly as hard to find. The Iraq War threatened the nation’s relations with the Middle East. China was rapidly industrializing and competing for resources. Major oil companies had just about given up on new discoveries on US soil, and a new energy crisis seemed likely.

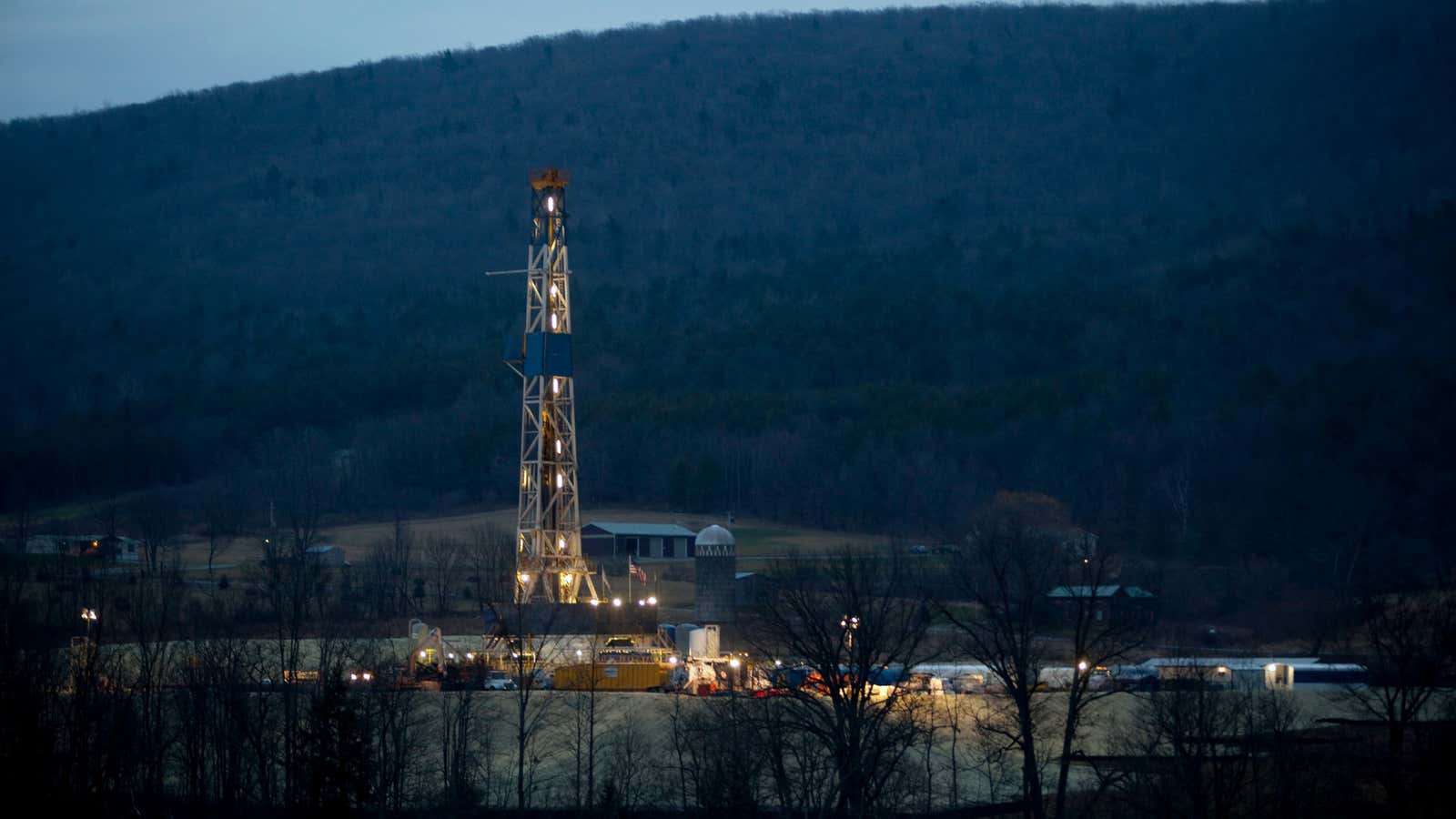

Far from the limelight, a few unknown wildcatters were working on ways to extract oil and natural gas from a compressed rock called shale deep below the ground. Exxon, Chevron and other giants dismissed their work as a waste of time. But by experimenting with hydraulic fracturing through extremely the dense shale—a process now known as fracking—these wildcatters started a revolution. In just a few years, the mavericks have put America on the road to energy independence, triggered a global environmental controversy and made—and lost—fortunes.

As I trekked the country to write a book about how the nation’s energy revolution unfolded, meeting ambitious wildcatters, and exhausted roughnecks in booming energy fields in North Dakota, Texas and Oklahoma, along with anxious homeowners in eastern Pennsylvania, a few questions guided my research:

Q: Are the frackers good or bad guys?

A: There’s little black and white about the nation’s energy revolution, which is what attracted me to this project. A group of maverick guys—and unfortunately they’re all guys—decided to buck conventional wisdom and try to find oil and gas in the US even as the giants scoffed. Chevron, Exxon and the others gave up on trying to coax energy from US shale layers. Instead, stubborn, headstrong entrepreneurs no one had heard of cracked the code. They created jobs, helped the country shift away from dirty coal, reduced the nation’s carbon dioxide emissions and revitalized small towns. Rather than depend on the Saudis and others for our energy, we’re going to be exporting gas and are on the road to energy security, if not complete independence.

Let’s be clear, though—fracking and drilling are industrial activities. They bring intense noise, traffic and disturbance to towns near wells. Frackers use a huge amount of water in the liquid mix used to frack, or fracture, the rock, which allows all the oil and gas to flow–about five million gallons per ell. Dust and engine exhaust is a hazard, as are emissions from diesel-powered pumps, and silica sand can lodge in lungs, potentially causing silicosis. While some of the biggest concerns about fracking are likely overblown, such as the fear that harmful chemicals will rise from the shale layers to invade water supplies, there are all kinds of examples of surface spills, leaks and poorly sealed wells that have done real harm.

Before my project, I had a clichéd view of energy guys—in Houston boardrooms, chomping on cigars, giggling as they pollute and drop off bags of money at the bank. When you spend time with them, you realize they’re often geologists, they like dealing with rock and being out in the fields. They own ranches, hunt and fish and many seem to care about the environment. But we need to pressure the frackers and scrutinize how they operate or dangerous mistakes will keep happening.

Q: Who are the frackers who have transformed the country?

A: George Mitchell is the father of fracking. The son of a Greek goatherder who made his way to the US, Mitchell spent decades running a midsized natural-gas producer in Houston. By the late 1990s, his company was running out of gas, his stock had crumbled and Mitchell and his wife faced serious health issues. Mitchell pushed his guys to figure out how to drill in shale. A young engineer who was about to be fired named Nicholas Steinsberger made a shocking discovery that was part luck, part brilliance. He changed the nation and the world.

Then there’s Harold Hamm. He grew up in a tiny town in Oklahoma and was so poor that he couldn’t begin school until it got cold, around Christmas-time, because he needed to help his sharecropper parents pick cotton in the fields. He didn’t go to college and was ignored by the biggest oil companies. But today his company, Continental Resources, is the leading oil producer in North Dakota’s Bakken region, Hamm controls more oil than anyone in the country and he’s worth $14 billion, or more than the estate of Steve Jobs. He’s going through a divorce and his wife will walk away with more money than Oprah Winfrey.

Aubrey McClendon was the scion of an Oklahoma energy family. As a young man, he teamed up with Tom Ward, a guy who came from the other side of the tracks. Ward overcame a really rough childhood—both his father and grandfather were alcoholics who died at young ages. Together they built the second-largest natural-gas company in the nation, helped pave the way for this energy resurgence, and at one point they each were worth about $3 billion. But McClendon and Ward lost much of their wealth and were kicked out of their companies after some huge mistakes, classic rise-and-fall stories.

There’s Charif Souki, an immigrant from Lebanon who knew nothing about fracking and was a banker and restaurateur until he decided to raise billions to build terminals to import natural gas. In 200, Souki realized the country was producing so much gas it was silly to try to import it and he had to figure out a way to save his career. In the end he made about $350 million and is leading a shift to export gas.

Q: Why is the nation so divided on fracking?

A: It seems we’re more divided than ever on almost any matter of importance. Just look at what’s happening in Washington. In many ways my book reassured me about the country. There are young people getting jobs and small towns are being revitalized. We’re innovating and taking risks. Immigrants and older people were key to this energy revolution, and they play some of the most important roles in my book. Two of the largest energy deposits of the past decade were discovered by sons of Greek immigrants—George Mitchell and Michael Johnson. It doesn’t get more American than that.

But when it comes to fracking and producing energy from these shale layers there’s little common ground. One camp says fracking poisons and should be abolished, the other snickers at health concerns and says “drill, baby, drill.” Many of the towns I visited are deeply divided between those who support and those who are against fracking.

Q: Should fracking be stopped?

A: To me, it’s unrealistic to try to outlaw fracking. About 90% of wells in the country are fracked, it’s just hard to extract any natural gas without fracking. Wind and solar aren’t yet ready to power the nation. It’s a lot to ask a nation still digging out of the biggest economic downturn since the Great Depression to forgo some of the largest gas fields in the world and keep sending money to nations we don’t really like so we can keep heating our homes. The best approach is to work with energy companies to improve the way they frack and drill. Keep their feet to the fire and pressure them to keep improving the way they drill and frack.

Q: Why is there a resurgence in the production of fossil fuels while we’re still trying to get the nation to embrace solar, wind and alternatives?

A: The Mitchell team worked on trying to get oil and gas to flow from shale for 18 frustrating years. Eureka moments are rare. Breakthroughs come from incremental advances, often in the face of deep skepticism. Frequently, they come from the dreamers, not the experts. We’ll get breakthroughs in alternative energy and it’s encouraging that so many are plugging away at it and already making improvements. It just takes time.