Independent lenders are giving more loans to US customers with bad credit, combining them into bonds and selling them on Wall Street. But this isn’t the housing nightmare of 2005, it’s car loans—today.

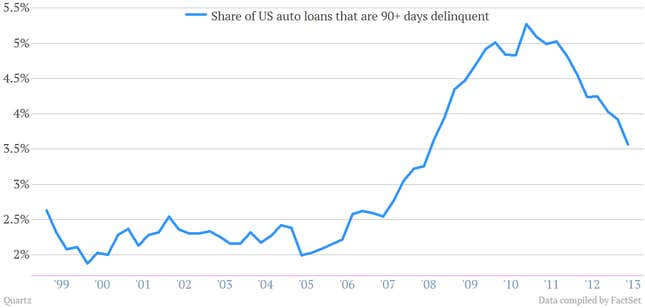

In August, the New York Federal Reserve noted that subprime auto-lending was beginning to return to pre-crisis levels. Private sector data now shows 27% of car loans for new vehicles this year went to borrowers with credit scores of less than 500, the highest share since tracking began in 2007, and $17.2 billion in bonds backed by these loans were issued this year, just below the $20 billion in 2005. That increase in subprime loans helped drive rising US auto sales, but it has regulators and consumer activists nervous that it’s not sustainable. Auto loan delinquency is falling, but it’s still not down to pre-crisis levels:

Driving worries about the sector are about a dozen non-bank lenders, often owned by automakers or financial institutions, which began providing financing for auto loans to dealers in 2010, after the passage of the US Dodd-Frank financial reform law. That law had created the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) to act as a watchdog for retail lending, but had explicitly carved out auto dealerships from supervision. This made consumer advocates nervous but had investors seeing an opportunity to charge high costs for loans at a time of low yields.

One key difference from the US housing bubble is that rating agencies aren’t putting a AAA stamp on securitized auto loans. While the lenders say that cars are easier to repossess than homes, the agencies say that the high loan-to-value ratio of the subprime loans means larger losses in the event of default.

Another difference is that the CFPB hasn’t given up on keeping an eye on auto loans. While it can’t supervise dealers directly, it can supervise any financial institution with more than $10 billion in assets, and it’s using that leverage to push back against pernicious practices in the sector.

The primary target is the mark-up that dealers will put on a loan, often as much as several percentage points above what they obtain from their financing company, which generates an estimated $25.8 billion in payments from consumers over the lives of their loans. Akin to the yield-spread premiums earned by mortgage brokers who shifted customers into subprime loans during the housing bubble, the CFPB is worried that the practice provides too much incentive for dealers to push car buyers toward a loan they can’t afford and wants the industry to move toward a flat fee for loan origination.

To forestall the practice, the CFPB is asking the lenders it does regulate to police dealers and ensure they are not discriminating against borrowers based on gender or race, spurring complaints from dealers and banks alike. (During the housing bubble, black and hispanic families who qualified for prime loans were sold more expensive subprime loans at a disproportionate rate.) Ally Financial, the former finance arm of GM that is now an independent bank, announced this week that the CFPB is probing its lending discrimination oversight.