This post originally appeared at 3DLT news. It serves as a rebuttal to our piece “It’s the end of Walmart—and mass-market retail—as you know it.”

I’ve noticed an important trend when writing about different retail markets. Usually there will be one or two “category killers” in each segment. Then Walmart, Amazon and eBay usually round out the top five. In the finale, I’m focusing on one of those, making the case for the world’s largest retailer.

All along I’ve written about real world products that could be 3D printed and sold online and in-store. From auto parts, to vacuum accessories, shower heads, light switch plates, holiday ornaments, phone cases, fishing gear, housewares and more. There’s a lot that can be 3D printed now and the technology is evolving fast. Databases full of digital products—potential new SKUs—are coming soon.

One of the big benefits of 3D printing is that it allows you to manufacture as close as possible to the point of need. Proximity matters, and not everyone will print everything at home.

Retailers with brick-and-mortar have a new advantage. Walmart is the world’s largest and has over 11,000 stores worldwide. They’re the big dog. While many specialty retailers could sell a line of 3D-printed products in their niche category, Walmart could sell all of them and at colossal scale.

Why 3D printing? What if in seven years, the market for 3D printed consumer products was somewhere north of $5 billion and growing fast. What if Walmart could get $400 million’s worth of market share by then? What if it found that offering 3D-print services could assist its mobile efforts, defend against showrooming, and reduce shrink? Wouldn’t it at least think about it?

It’s doing more than that, it’s already offering a 3D imaging and printing service in-store. Walmart recently launched a test at the York store of its UK affiliate, Asda. Whatever the outcome of the test, Walmart is learning about 3D printing, and soon it will put that knowledge to work.

Specialty retailers who wish to compete for digital sales in their category must now run with the big dog.

Walmart’s sheer size is hard to fathom. It generated $470 billion in revenue last year. If Walmart were a nation it would have one of the largest economies in the world. Eight cents of every dollar generated in the US is spent at Walmart. It handles over 7.2 billion transactions yearly equating to more than 1 million transactions every hour of every day.

Consider the grocery business for a moment. Walmart opened its first “supercenter” in 1988, combining general merchandise with a full-scale supermarket. In 25 years, it’s built over 3,100 supercenters and now owns a commanding 38% share of the US grocery business. Prior to Walmart’s entry, Cincinnati’s Kroger Company was the US’s largest grocery retailer. It now has a 9% share of a market in which it was once the category leader.

How did Walmart do it? Part of it is location and part is price. Over 90% of people in the US live within 15 minutes of a Walmart. Its real estate is a significant competitive advantage. But, to achieve its goal of “everyday low prices,” Walmart was and is intensely focused on reducing costs.

Walmart’s strategic sourcing goal is to find products at the best price from suppliers who are in position to meet its demand. Walmart establishes partnerships with most of its vendors, offering long-term relationships and high-volume purchases in exchange for low price.

To remain competitive, many Walmart suppliers produce abroad now. According to Charles Hood, author of the book Walmart Egonomics Always, revealed that “over 90% of the products Walmart sells are manufactured in foreign facilities.”

As far back as the 1980s, Walmart was busy computerizing its point-of-sale systems and creating its own private satellite network. Doing so gave the company access to all kinds of data about products and the customers who purchased them. Now Walmart has the largest information technology infrastructure of any private company in the world.

Walmart leverages data to drive cost out of its supply chain. State-of-the-art technology allows Walmart to accurately forecast demand, track and predict inventory levels, create highly efficient transportation routes, and manage customer relationships.

From the size of its orders, to the packaging used and delivery method, Walmart carefully orchestrates the way it moves product.

Walmart’s supply chain strategy delivered several competitive advantages, including lower product costs, reduced inventory carrying costs, improved in-store variety and selection and highly competitive pricing for the consumer.

Along came Amazon

Amazon launched in 1995 and, in less than 20 years, has grown to a $61 billion business. With the same promise of long-term partnerships and high-volume purchases, Amazon was able to achieve low product cost. With an e-commerce business model, it didn’t need thousands of stores, greatly reducing its logistics and inventory costs. Those things, among others, made it competitive with retailers. Then Amazon evolved into a marketplace, allowing third-parties to sell on its network and drop-ship products directly to consumers. This transferred the cost while greatly improving the variety and selection of Amazon’s products, making it even more competitive.

While it’s still dwarfed by Walmart’s size, Amazon has found other competitive advantages, including the practice known as showrooming, where a consumer examines a product in-store and purchases it online. In fact, in one recent survey, 64% of consumers polled said they had showroomed Walmart and purchased at Amazon. Another recent survey of smartphone users suggested that nearly 50 million people access Amazon each month and “only” 16.3 million access Walmart.

While the proliferation of smart devices has made showrooming practical, online commerce, in general, and the mobile channel, specifically, still represent a big opportunity for both companies.

Walmart’s e-commerce sites will generate approximately $9 billion in revenue this year and roughly 40% of Walmart’s online traffic this holiday season will come from mobile devices. With that kind of opportunity its easy to see why it’s estimated that Walmart will spend $300 million on its e-commerce and mobile platforms this year alone.

Could 3D printing play a role in mobile?

Walmart is already driving up to 40% of its traffic from mobile and the channel will become even more important. Smartphones and tablets are quickly replacing PCs as the primary tool for web browsing (and online purchases). By 2016 L2ThinkTank.com predicts that mobile commerce will drive $31 billion in direct revenue, and will also influence another $689 billion in offline sales. If retail is a $4 trillion business, within three years mobile could impact nearly 18% of all retail purchases.

Retailers like Walmart are doing everything they can to build their mobile presence. They’ve built dedicated apps, they deliver mobile ads and coupons, they’re advertising their mobile platform and including interactive features in their point-of-purchase marketing. Some are even redesigning their entire stores around the mobile experience.

Mobile is also having an impact on payment. Over the last 30 years, the adoption and use of credit cards has grown to the point where it is now nearly ubiquitous. Merchants like Walmart pay a percentage of each transaction in credit card “swipe fees.” All told, swipe fees cost retailers and consumers over $50 billion in the last year alone.

While retailers are pitching mobile payment as a convenience for their customers, they (and telecoms, among others) are also looking at it as a way to circumvent the banks charging the fees. As mobile payment continues to roll out, retailers will place even more emphasis on programs that drive mobile eyeballs.

A web-based service

A 3D-printing service offered by any major retailer would require a web-based system to manage uploads, products, sales, deliveries and tracking. While some products could actually be ordered through store point-of-sale (POS) systems, it’s more likely products would be ordered via the web (from home) or a mobile device (in-store). It’s also conceivable that mobile devices could be used to receive product (opening the lockers where finished products would be placed for pick-up, for instance).

App and game integration

Further, as apps and games continue to proliferate, a retailer like Walmart would have the opportunity to integrate its services. For example, consider the “Lets Create! Pottery” app from Infinite Dreams. It allows you to design a piece of pottery and submit the design for 3D printing.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lf8vK-pFlY4?feature=oembed

Imagine the scenarios that could play out there. This kind of integration is a win for both the developer and the producer, while offering retailers the secondary benefit of even more exposure on mobile devices.

Could 3D printing reverse showrooming?

Integrating digital manufacturing with mobile could even help Walmart combat showrooming. Since they’re digital, 3D printable products would only be available online. Assuming production could happen quickly enough, it’s conceivable that consumers would view those products from their mobile devices and purchase them in-store—the opposite of showrooming, where people view products in-store and purchase online.

People buy books, music and movies online for three key reasons. First, there is little benefit to seeing the physical product. Second, because there is such little supply chain cost, digital products can be sold less expensively. Finally, because digital books, music, and movies can be delivered instantaneously, there is no time advantage to buying in-store.

If in the end, we’re talking about physical products (not digital files); the user will need a way to touch and feel them. Where better than a retail store, where samples can be displayed?

Remember service merchandise? It was a retail store that displayed a sample of each product on the floor. To make a purchase, the customer took a slip of paper to the register, paid, and then waited for the product to slide down a chute from the warehouse.

Unraveling the supply chain

Discussing 3D printing’s potential impact on the supply chain can be a bit dangerous. Retailers have spent millions to optimize their supply chain technology and processes. What they’re really doing is making the train faster. It’s still a train and by definition, limited to the tracks.

I’ve written extensively about how digital manufacturing could impact the supply chain, but here’s the Reader’s Digest version: There’s little of the upfront cost required with mass manufacturing, no packaging, no logistics, no inventory and none of the waste associated with trend-spotting and forecasting.

What about home printing?

While digital works well with media, it will be more challenging with physical products.

In the near term at least, the cost and complexity of digitally manufacturing at home will be prohibitive for most people. Then there’s the issue of materials. High-end 3D printers can print 10 or more substrates. Home 3D printers are typically limited to plastic.

In the longer term, the technology will improve, but there will always be times when you can’t or won’t want to do-it-yourself. Those decisions will be determined by the quality, cost, and time of printing at home versus elsewhere. In those instances you’ll have a choice: Manufacture online and have your product shipped, or order online and have your product manufactured in-store.

Local production creates the lowest possible supply chain cost. This is not to say that digital manufacturing won’t happen remotely, only that the ability to offer both options is a big advantage.

Will 3D printing replace mass manufacturing?

Note that I am not suggesting that digital manufacturing will replace mass manufacturing, now or ever.

What I am saying is that they will complement each other. We’re a long way from being able to 3D print a smartphone or TV. Those will continue to be mass-manufactured (though 3D printing will play a bigger role in their production). But, the list of products that can be manufactured digitally grows every day.

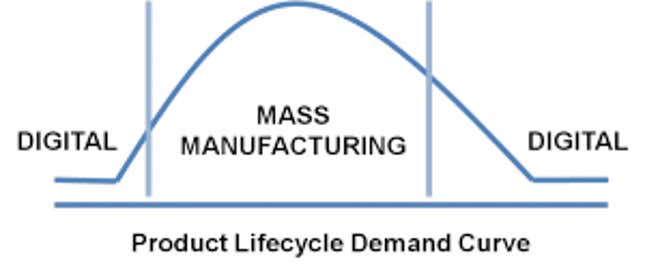

A savvy retailer like Walmart would probably offer products digitally at the beginning and end of their lifecycle.

When products reach stride they’ll stock cheaper, mass-produced versions, and when demand tapers off, they’ll continue to offer them in digital format. The retailer will be able to make that decision based on its own data, not some analysis of industry trends.

The cost of loss prevention

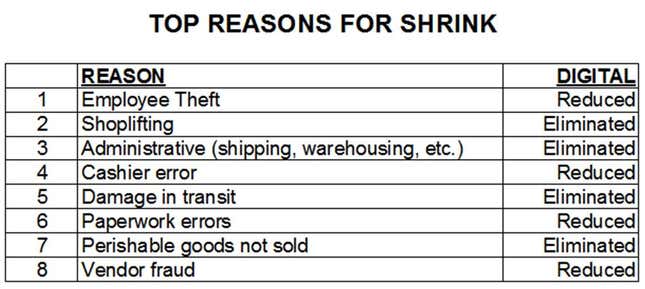

In 2007, it was estimated that Walmart’s loss prevention cost was more than $3 billion. In 2011, the University of Florida’s National Retail Security Survey revealed that the average shrink percentage in the US retail industry was 1.42% of sales. The major causes are as follows:

Since a digital product would only be produced upon order (and payment confirmation) many of the causes of shrink would be greatly reduced or eliminated entirely.

Handling returns in a digital world

I’ve been asked how a retailer like Walmart might handle returns of digitally manufactured items. In 2009, the National Retail Federation’s Customer Returns in the Retail Industry Report pegged returns at 8.02% of sales across the industry. Of that, 83.6% of returns were accompanied by a receipt.

It can be very difficult for a retailer to know whether a mass-produced product was sold by it or someone else. If a product is ordered digitally, a receipt is always available. Like 2D digital printing, security features can be built into 3D printed products allowing the retailer to know if the product was theirs.

Like any other SKU, digitally-manufactured products will be legitimately returned for many reasons. But what about all the other returns retailers must contend with? Non-receipted returns account for 16.4%. Included in that is return fraud which accounts for 5.2-8% of all returns.

If by 2020, Walmart was able to build a thriving 3D-printing service, the reduction in shrink and lower cost of returns could help make it a very profitable chunk of revenue for the company.

Could Walmart build a business of that scale, that quickly?

It could because it has. Here is the math. 3D printing has been forecasted to be a $7.6 billion business by 2020. 3D imaging, including software, design, and scanning is projected to be a $9.4 billion business. Together, that’s a $17 billion industry. Another estimate recently said that currently, roughly 28% of all 3D printing is for consumer use (the remainder was for prototyping). By 2020, 80% of 3D printing is forecasted to be for consumer use.

Taken together its possible to assume the addressable market (consumer products) could by then be a $5 billion industry. If Walmart were to attack it, is it realistic to believe it could own an 8% market share? It gets 8% of every dollar spent in the US now. In 25 years, it’s been able to grab 38% of a grocery market that was already highly competitive. 3D printing is wide open and an 8% share (based on the assumption above) would equate to $400 million in sales.

Look at it this way. Walmart stocks over 100,000 SKUs in its stores and offers over a million on its website. Is it possible by then, that the company’s digital manufacturing service could offer 10,000 products? That’s 1% of its total offering. I realize there are more variables at play here, but %1 of $470 billion in revenue is $4.7 billion.

Then there’s the intangibles. Since the products would be produced locally, it would definitely reduce Walmart’s percentage of foreign-made goods. It would make on-boarding new suppliers easier and make mass-production more profitable. 3D printing would drive traffic to Walmart’s stores and its online properties. How would that impact the number of transactions and the average sale?

Consider mobile again. By 2016, it will drive $31 billion in direct revenue, yet influence $689 billion in offline spend. Could digital manufacturing have a similar effect? If so, $400 million in sales could theoretically drive billions in additional sales.

Meet the new boss, same as the old boss

Assume for a moment that by 2020, any other retailer could derive 1% of its sales from digital manufacturing. For Kroger, 3D printing would be a $90 million business by then. Target and Costco could each pull $70 million. Home Depot, Walgreens, and CVS Caremark could be generating $60 million each. Lowe’s could drive $50 million and Safeway and Best Buy could each generate $35 million in 3D-printing revenue.

That seems fine on paper, with everyone getting their fair share. But here’s the problem. Walmart is the big dog, and they’re already running the race. Other retailers are stuck in the starting block.

Like e-commerce before it, to the victors go the spoils, and those who delay, usually pay.

In an effort to compete with Amazon, retailers spent billions to build and market their web platforms. Soon, they might be spending billions to build and market 3D-printing services, though this time in an effort to keep up with a Goliath already 10 times their size. Not an enviable position.