Foreign aid is streaming into the Philippines from around the world as the news of the devastation wrought Super Typhoon Haiyan spreads, but it’s no longer just food, water and shelter: Before the storm even made landfall, a team from non-profit Télécoms Sans Frontières was on the ground, carrying satellite phones and laptop-sized BGans, which enable voice calls and internet connections via satellite.

TSF set up in Tacloban, one of the areas in the storm’s path, on Nov. 7. After much of the region was flattened and telecommunications and electricity knocked out, the group started offering storm survivors free three-minute calls to loved ones—and just as crucially, offered ways for search and rescue teams to communicate with each other.

You can read more about how TSF works and what they’re doing on the ground in the Philippines in The Atlantic. The group’s rapid reaction underlines the critical role that mobile communications now play in disaster relief and humanitarian aid

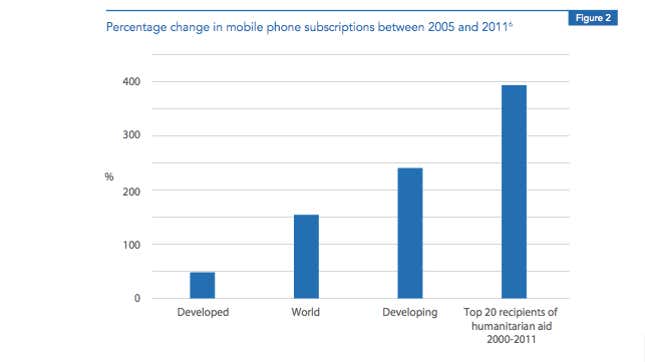

Just fifteen years ago, having a mobile phone connection would have been an unachievable luxury for those in the midst of a natural disaster. But the massive growth in mobile phone usage has radically changed the equation—and usage has been growing the fastest in the countries that have been the biggest targets of humanitarian aid:

Mobile communications are also improving the way that aid is delivered, allowing for better coordination of resources. Adding Twitter, Facebook and other social media has only accelerated that change, as could be seen this week as the massive Filipino diaspora took to social media to find friends and relatives after Typhoon Haiyan. A recent United Nations report (PDF) on “Humanitarianism in the Networked Age” is full of similar examples:

On 6 August 2012, Kassy Pajarillo issued an urgent appeal on the social network Twitter: her mother and grandmother were trapped by surging floodwaters in the Filipino capital, Manila, could anybody help? Within minutes, emergency responders had dispatched a military truck, and her family was saved.

What’s next could be even more radical, aid experts say. In the very near future, emergency response teams can use mobiles to deliver maps the victims and aid workers, deliver live first aid advice, use cellular signals to find people in the rubble, and use multiple cell phones to create small “mesh networks.”

The world is becoming “a place where everyone has a computer in their pocket, and that changes our ability to provide them with aid,” Paul Margie, the US representative for TSF, told Quartz.

As aid organizations adjust to the new mobile-enabled developing world, mobile payments might take the place of some food aid shipments. “That’s the big conversation,” Margie said. Rather than driving trucks full of food into disaster hit areas, food, aid organizations and charities might bring (or send) vouchers for food instead. “We need to think about emergency response the way that FedEx thinks about delivering packages—we need to take advantage of the infrastructure we’re given,” said Margie.

Soon after emergencies happen, the private sector, which has a much better-established infrastructure than aid agencies, is often up and running again. “The food is often there, people just don’t have the money to buy it,” he said.