The Chinese Communist Party just announced that it is loosening its one-child policy, allowing most of the remaining couples in the country who were restricted to one child to have two. That’s great and all. But it comes way too late to fix the huge glitches in China’s economic growth model that its family-planning policies created—namely, its yawning gender imbalance and rapidly aging population.

A big reason it’s too late is that it’s not the one-child policy that’s holding back many couples from having more children. Rather, it’s the spiraling costs of living in cities, where the one-child policy was mainly enforced, says Leta Hong Fincher, a PhD candidate in sociology at Tsinghua University and author of a forthcoming book on gender inequality in China.

“The central government’s announcement to loosen the one-child policy will of course result in some couples choosing to have two children who otherwise wouldn’t have done so,” Hong Fincher tells Quartz. However, “[M]any young Chinese who say they don’t want to have any children at all because the cost of living in the city has become so expensive.”

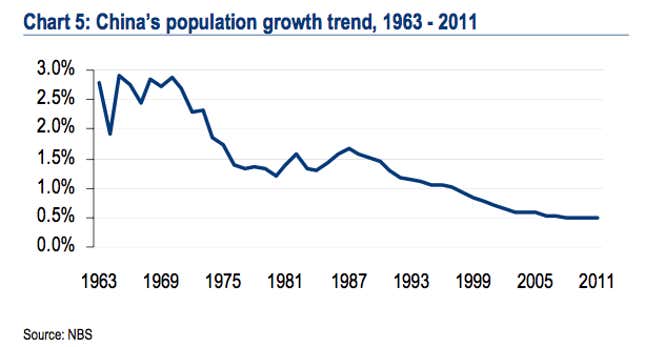

That’s bad news—at only 1.4 births per woman among young women, China’s fertility rate is already dangerously low. The country needs to bump that to 2.1 to offset the gender imbalance and demographic decline.

And then there’s the timing problem. Sure, China’s population will continue to grow until 2030, when it hits 1.45 billion. But that growth isn’t mainly coming from babies being born. The big driver is more old people living longer.

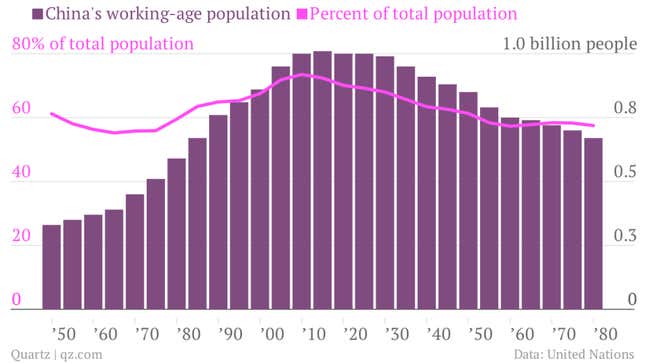

Let’s say couples do start cranking out more than 1.4 kids. At the absolute earliest, those kids will begin to enter the workforce in 2035. That’s not soon enough. China’s working-age population peaked in 2012 according to official statistics, at 1.0 billion people. In 2025, the (now) 930 million-strong labor force will start shedding 10 million workers a year.

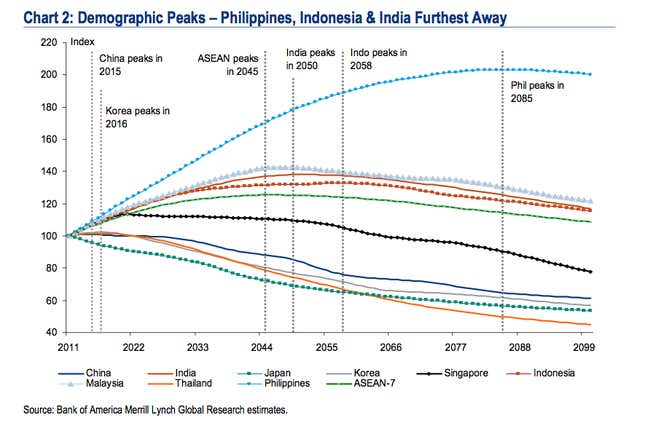

That means China is already facing a competitive disadvantage to many of its neighbors, as you can see from the chart below, which shows working-age populations. An extra injection of kids will make the decline of China’s workforce a little less steep after 2035, but it won’t reverse the trend.

Then there’s the gender gap. By 2020, China will have between 30 million and 35 million more Chinese young men than women. This is alarming for both Chinese society and the economy.

But, again, that’s more than two decades before the new policy starts having an impact. And unless raising children becomes cheaper, the two-child policy won’t change a cultural preference for boys that caused the gender skew in the first place. Sex-selection techniques remain widely still available.

This isn’t to say the two-child policy isn’t a big deal for president Xi Jinping. To change the policy, Xi overcame the National Population and Family Planning Commission, a bureaucracy with such a powerful hold over the Party that it earlier today confidently dismissed rumors that the one-child policy would be relaxed. The NPFPC employs millions in the enterprise of collecting fines from violators of family planning laws. It also carries out forced abortions and sterilizations. This has earned it widespread resentment among Chinese citizens. So count this as a big win in spirit for Xi and company, even if in practice it’s much less exciting.