The city of Tacloban, devastated by Typhoon Haiyan (or Yolanda, as it is known in the Philippines) is finally showing signs of rebirth.

A handful of business have recently opened, according to government reports, with ATMs coming online and stores selling their wares along the city’s main streets. While thousands of survivors have fled to nearby communities, dismayed by the damage and a local government so dysfunctional that corpses still haven’t been picked up, others are starting to rebuild homes and businesses from the rubble. “For Taclobanos, life will go on,” a local television station promised.

But should life return to normal? Many climate change and disaster preparedness experts say that rebuilding the 78-square-mile town of 220,000, where hundreds were killed by the storm, is a grave mistake.

Rebuilding “needs to be done urgently and differently for the Philippines,” Vinod Thomas, director general for independent evaluation at the Asian Development Bank, told Quartz. “There is clearly a big lesson to be learned in not relocating in a highly vulnerable area,” he said. “Tacloban is like a poster child. You can’t imagine a more vulnerable area than Tacloban.”

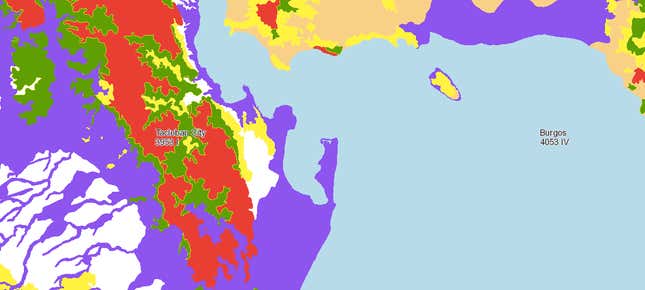

All of the Philippines is vulnerable to rising seas and intense storms caused by climate change, but Tacloban—situated at the mouth of a bay and with major portions of the city well below sea level—is in a uniquely precarious position. The vast majority of the city that is near the coast, and all of its densely-populated peninsula, is in an area of “high” to “moderate” flood danger, which is marked in purple on this geohazard map created last year:

Further inland, residents are extremely vulnerable to landslides (those areas in danger are shown in red) from the mountains that hug the west and north of the city.

The city has become a magnet for migrants from nearby villages—its population increased 62% between 1990 and 2010. The surge of new residents produced some unintentional consequences that made the city even vulnerable—increased drilling for fresh water lowered ground levels in some areas, for example.

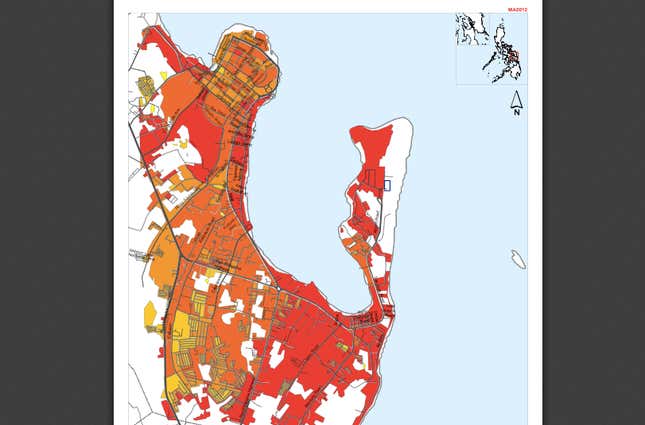

After the storm hit, the devastation on the peninsula of Tacloban was almost complete. Areas in deep red are “totally damaged:”

World Wildlife Fund officials happened to be studying the city to suggest preparations for a “worst-case” scenario storm in the weeks before Haiyan hit. Now, after the storm, the group has concluded that “it is more logical to relocate” rather than rebuild, WWF project manager Moncini Hinay told Quartz. “If the city and its citizens do want to rebuild, there are two options,” he said. “Rebuild but elevate, or move to a safer place, away from the sea, move the city center, move the airport and relocate the schools.”

Areas just 10 kilometers inland suffered little damage from the storm, Hinay said. Still, their proximity to landslide-prone areas makes them vulnerable in other ways, he said.

Relocating residents and businesses from coastal areas is often a tough emotional and political battle, even with the increasing vulnerabilities of these areas to climate change. Many Filipinos in cities like Tacloban own the plots of land where their homes reside, so government decrees to move will need to come with financial compensation and similar, safer, land in exchange. That would carry a huge price tag, and since so much of the country is vulnerable to natural disasters, finding a suitable site for resettlement is no easy task.

Other cities have been forced to make similarly difficult decision in recent years after natural disasters. In Indonesia, some residents of Aceh were moved hundreds of meters inland into identical concrete homes after the 2004 tsunami that killed 170,000 in the area, but land disputes and protests still marked the rebuilding effort five years on.

In wealthier countries, voices questioning whether to rebuild after recent disasters have been quickly struck down. Geologists who suggested after Hurricane Katrina that the below-sea-level city of New Orleans not be rebuilt, or the that the mid-Atlantic US reconsider coastal construction after Hurricane Sandy, were labeled unpatriotic or just plain ignored.

Filipino urban planner and architect Felino Palafox has proposed shifting a rebuilt Tacloban to higher ground, and the national government has promised to help Tacloban residents and others affected by the storm to either rebuild or resettle in less vulnerable parts of the city. “Yolanda has shown us which areas of the city are vulnerable and we will be coordinating with the local government to map out a resettlement plan,” Philippine vice president Jejomar C. Binay told the Philippine’s TV5.

But incremental measures to reshape the city may not be enough, especially since the dozens of typhoons that batter the Philippines each year are set to become more severe due to the multifaceted effects of climate change.

“Filipinos are resilient and we have withstood many storms over the years,” Hinay said. “But Yolanda was something different.”