Hong Kong’s labor market is becoming a compact example of the labor problems stalking China—there are not enough people who want to fill blue- and pink-collar jobs like waiting tables, working in shops or performing manual labor. In status-conscious Hong Kong, where nearly half of employed workers define themselves as “managers,” “professionals” or “associate professionals” (pdf pg. 2), some businesses are feeling the shortage acutely.

“I’m just looking for people with basic manners,” one restaurant manager recently told Bloomberg News about his difficulties hiring. “You just have to be mobile and know how to smile.” Waitstaff jobs can come with benefits including medical, dental and life insurance, education subsidies and even use of the company vacation home. At around $2,000 a month, the salary is comparable to an associate salary at a private equity firm or investment bank (pdf page 4).

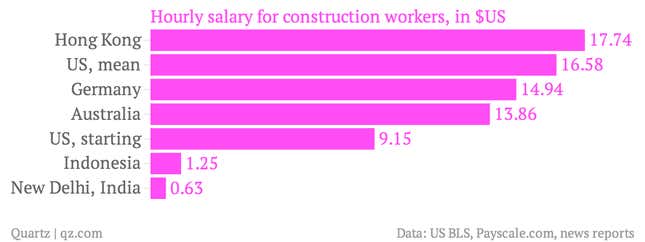

No where is the labor shortage more apparent than in the construction industry. Ongoing project construction sites were reporting a 15% labor shortage earlier this year. A cement mixer with “no experience” is getting paid HK1,100 ($142) a day, the head of the Hong Kong Construction Association told The South China Morning Post this week. That works out to nearly $18 a hour for an 8 hour day, well above starting salaries (and many average salaries) for the industry in the rest of the world. (All salaries below are minimum or starting salaries for unskilled workers unless otherwise indicated):

Hong Kong—like mainland China only more so—is plagued by an aging population and an increasingly educated youth that are choosing office jobs over manual labor, and the shortage is only expected to get worse. The city’s total labor force will rise from 3.59 million this year to 3.71 million in 2018, then drop to 3.52 million in 2031, according to recent Census and Statistics Department projections (pdf pg. 6). That will mean 14,000 fewer people than jobs by 2018, the agency said.

Hong Kong has compensated in the past where pink-collar labor was lacking by allowing hundreds of thousands of immigrants, mostly women, to live and work here as “domestic helpers.” Now other industries are clamoring to be allowed to import more labor, including, not surprisingly, the construction industry.