As the story goes, a big part of the reason we push to get women on corporate boards is that they bring a new perspective. Diversity of opinion. A way to counter a cowboy group-think fueled by testosterone.

So it is perplexing at first to learn that, when you ask more than a thousand board members what they think about the economy, regulation and the importance of risk management, the women fall in with opinions remarkably similar to those of the men.

The greatest obstacles to achieving strategic objectives? The regulatory environment, according to 42% of women, 45% of men.

Top political issues relevant to their director roles? Unemployment and the economy, say 71% of women, 69% of men.

“Gender differences practically disappeared when we looked at how men and women directors think about issues like the economy,” says Bonnie W. Gwin, managing partner at Heidrick & Struggles, which, with WCD, a global organization of women corporate directors, sponsored the “2012 Board of Directors Survey” of 1,067 board members in 58 countries.

And there, the harmony pretty much ends.

Gender tensions eclipse the veneer of accord once you get down to asking board members about quotas.

Whether you are in the ivory tower at Harvard Business School, where Dr. Boris Groysberg and researcher Deborah Bell conducted the survey of directors, or in Brussels, where European Union Justice Commissioner Viviane Reding is calling for mandatory quotas of women on corporate boards, it’s an instantly polarizing issue.

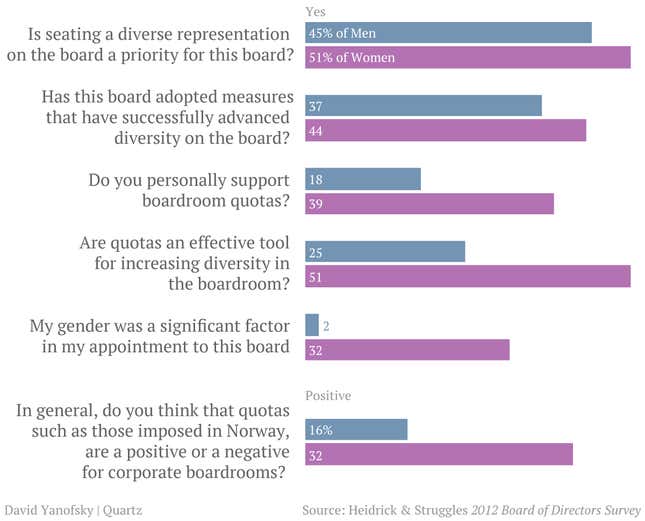

Go back to those otherwise concurring board members and ask what they think about quotas and 51% of the women agree that quotas are an effective way to increase diversity in the boardroom, but only 25% of the men do.

Reding wants to see women occupying 40% of board seats at large EU companies by 2020, and is calling for a law to impose sanctions on those who don’t hit the goal. Her crusade has not won her any popularity contests.

Nine EU countries pushed back with a letter last month, noting, among other things, that they could handle the gender-on-boards problem themselves. Reding’s comeback: “Thankfully, European laws on important topics like this are not made by nine men in dark suits behind closed doors, but rather in a democratic process.”

Reding has a simple response to the argument that we don’t need a law to slap gender quotas on companies: Cajoling, begging, and self-regulation to boost women’s ranks at the top have all been failures. Besides, she says, a string of persuasive studies has concluded that companies with women on their boards perform better, and that’s good for the economy.

At a speech at the Harvard Club in Brussels on October 8, Reding said that despite official arm-twisting recommendations in 1984, 1996 and 2011 that companies boost women’s representation, there’s been “no progress” in the EU. Only 13.5 % of board members in Europe today are women, which amounts to an average 0.6 percentage point a year gain since 2003. Her very vocal opponents say Reding just has to give them a chance to get some women into the pipeline.

Susan Stautberg, co-founder of WCD, says board quotas “really have worked” in the wake of legislation in European countries including France. But she and others say the idea would be dead on arrival in the US “Our business and regulatory culture is more likely to embrace market solutions than mandates,” says Joe Keefe, president of Pax World, a socially responsible investment manager. Keefe spearheaded a campaign in June to send letters to the 41 companies in the Standard & Poor’s 500 that had no women on their boards. Fourteen responded. There’s “substantial research” to support the idea that companies deliver better financial results when women are on boards and in upper management, says Keefe, who adds “there are plenty of qualified women.”

The pipeline has been filled for decades. Sometimes, the problem is just old-fashioned sexism that can’t be cured by friendly negotiation. Reding has figured that out.