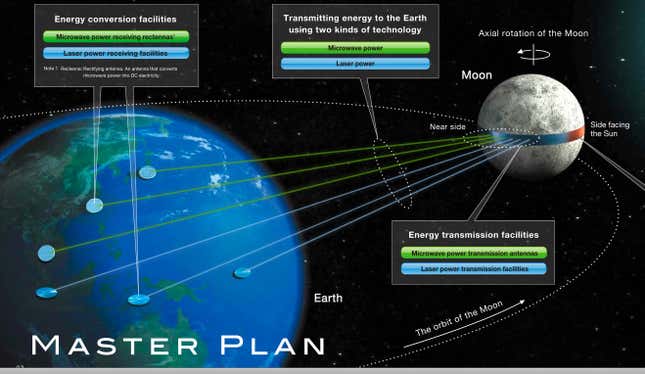

Shimizu, a Japanese architectural and engineering firm, has a solution for the climate crisis: Simply build a band of solar panels 400 kilometers (249 miles) wide (pdf) running all the way around the Moon’s 11,000-kilometer (6,835 mile) equator and beam the carbon-free energy back to Earth in the form of microwaves, which are converted into electricity at ground stations.

That means mining construction materials on the Moon and setting up factories to make the solar panels. “Robots will perform various tasks on the lunar surface, including ground leveling and excavation of hard bottom strata,” according to Shimizu, which is known for a series of far-fetched “dream projects” including pyramid cities and a space hotel. The company proposes to start building the Luna Ring in 2035. “Machines and equipment from the Earth will be assembled in space and landed on the lunar surface for installation,” says the proposal.

If that sounds like a sci-fi fantasy—and fantastically expensive—it’s not completely crazy. California regulators, for instance, in 2009 approved a contract that utility Pacific Gas & Electric signed to buy 200 megawatts of electricity from an orbiting solar power plant to be built by a Los Angeles area startup called Solaren. The space-based photovoltaic farm would consist of a kilometer-wide inflatable Mylar mirror that would concentrate the sun’s rays on a smaller mirror, which would in turn focus the sunlight on to high-efficiency solar panels. These would generate electricity, which would be converted into radio frequency waves, transmitted to a giant ground station near Fresno, California, and then converted back into electricity.

Unlike terrestrial solar power plants, orbiting solar panels can generate energy around the clock. The part-time nature of earthbound solar power means it can’t currently supply the minimum or “baseload” demand without backup from fossil-fuel plants. However, the cost of lifting the solar panels into orbit would be far higher than for building a photovoltaic power plant on earth.

Not much has been heard from Solaren since then, but last year Michael Peevey, president of the California Public Utilities Commission, said in a speech that the project was still under development. “Although this sounds like science fiction, I am hopeful that recent advances in thinner, lighter-weight solar modules will make this technology feasible,” Peevey said. “I believe it is worth taking a chance on this technology because as a baseload resource, space-based solar may help to displace coal-fired capacity that would otherwise meet those needs.”

But even if the energy that eventually comes from a solar power plant on the the Moon justifies the costs of building one—not to mention the fossil fuel you have to burn to get the machinery up there—Shimizu’s greatest hurdle may be staking a claim on all that lunar real estate, points out Wired. “Outer space law is notoriously difficult to apply in practice and may scupper the plans long before anything gets built.”