Goldman Sachs has long been considered the leader of the pack on Wall Street, and that includes being a trend setter when it comes to pay. In the heady days of the 1980s and early 2000s, the storied investment bank typically paid its employees much more than rival firms to attract the best talent. And in the more austere post-crisis environment, it’s been aggressive in paring back “comp” as it seeks to jack up returns for its investors. Employee compensation at Goldman fell to 41% of revenue in the first nine months of this year, its lowest level since the company went public in 1999, and down from 44% a year earlier. By comparison, JP Morgan’s compensation to investment bank employees fell one percentage point, to 34% of revenue over the same period.

Now, as investment banks face another uncertain year, Goldman’s own research analysts believe the company could again spur copycats. It describes 2014 as a year when major banks will be “running harder” just to stand still: For instance, growth in bank capital markets, wealth and trust businesses will be almost completely offset by an expected 50% decline in mortgage banking revenue, it says.

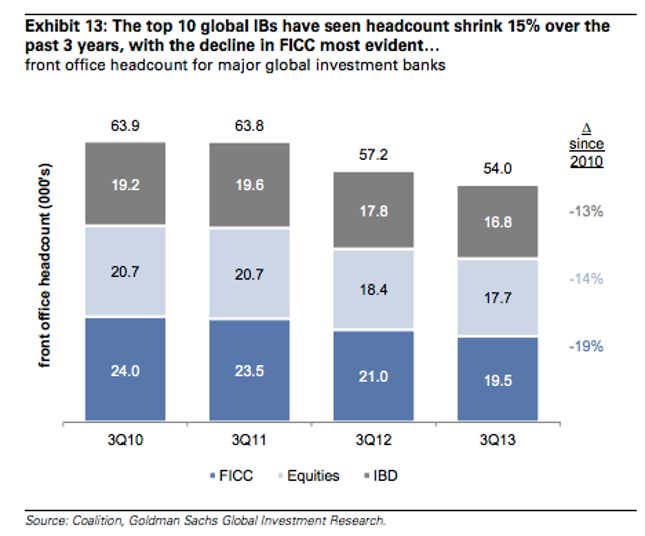

One obvious way for banks to boost earnings if “top line” (i.e. revenue) growth doesn’t happen is by further reducing what they spend on pay. That’s typically achieved through job cuts and lower bonuses. Goldman says that the top 10 global investment banks have laid off 15% of “front office” staff (bankers, traders, and analysts, as opposed to administrative staff) since 2010. Bond and currency trading desks (FICC in the chart below) have been hit harder than stock traders (equities) or dealmakers (IBD).

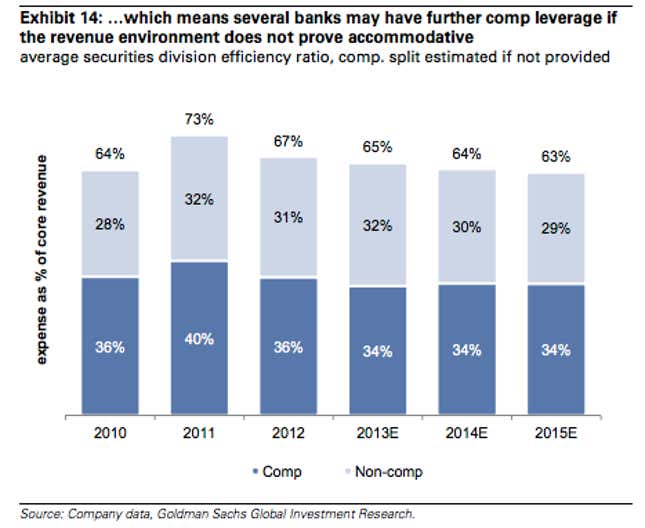

This has compensation relative to revenue to fall across the industry. But if revenue doesn’t pick up, banks still have room to cut more even jobs and trim bonuses further to keep a lid on pay, Goldman says.

And even if revenue does grow, banks may hold on to more of rather than distribute it to employees, for the sake of the bottom line. That would never have happened before the crisis, when competition for talent was fierce. But with tens of thousands of laid-off bankers sitting on the sidelines, its safe to assume those days are behind us.