How does a company keep growing when it’s reached pretty much all the customers it can? Digicel, a mobile operator with nearly 14 million subscribers, is no behemoth by telecom standards; but having specialized in small countries, it has hit the limits of its expansion. The solutions it has found could be instructive for larger rivals that face the same conundrum.

It all started with an ad in the Financial Times. In 2001, Denis O’Brien made €285 million ($253 million at the time) from selling Esat, a telecoms operator he set up in Ireland. He then considered setting up a mobile network in sunny Trinidad, just off the coast of Venezuela. That didn’t work out. So when he saw an ad for mobile licenses on sale in Jamaica, he jumped at the chance.

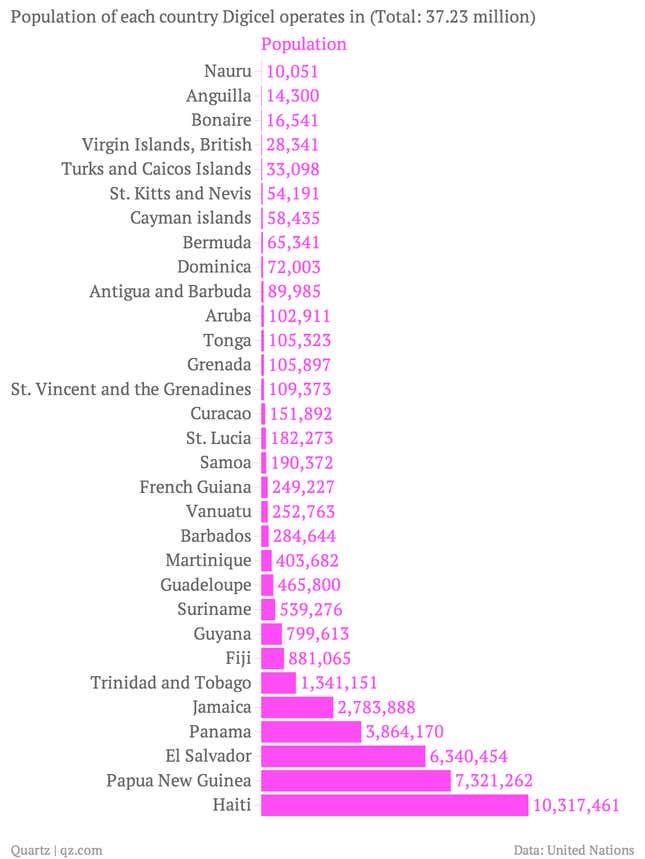

Digicel signed up 100,000 subscribers in 100 days. Buoyed by this early success, the company expanded rapidly across the Caribbean, snapping up licenses and acquiring businesses as they became available. In 2006, it made its first move to another neglected chain of islands, and bought a network in Samoa, in the South Pacific. By 2009 Digicel was in another five countries, all of which it set up from scratch, ranging from tiny Nauru to Papua New Guinea.

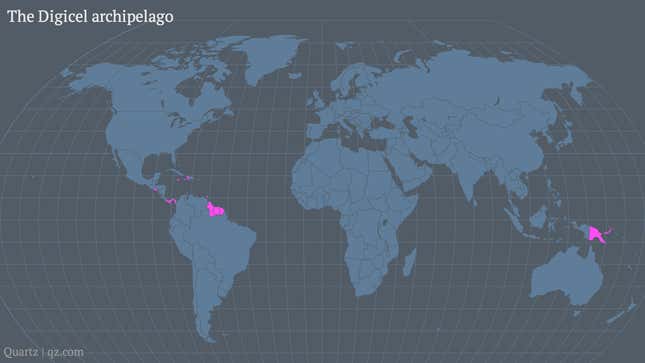

Today, Digicel operates across 31 countries in the Caribbean, Latin America and the Pacific. Its footprint is vast, covering just over a million square kilometres (413,000 sq miles) of land, an area more twice the the size of California, albeit scattered across half the globe. All the while, its main office has remained in Ireland, O’Brien’s home (though the company is registered in Bermuda).

To the ends of the earth

Digicel built its business model around going to small, difficult countries that larger companies would avoid. These countries are challenging environments that “you’d run a mile from” because they don’t seem to have the resources to afford mobile telephony, says Colm Delves, Digicel’s CEO.

Yet with fixed-line phones a rarity, people were ready to snap up any means of communication they could afford. It wasn’t always easy. In the jungles of Papua New Guinea, the company lost nine workers to fatal accidents. In Haiti, existing networks refused to connect to Digicel. Yet within a month, it had signed up 100,000 customers there, after planning for 300,000 over five years, says Delves. The other networks quickly relented.

To the end of the road

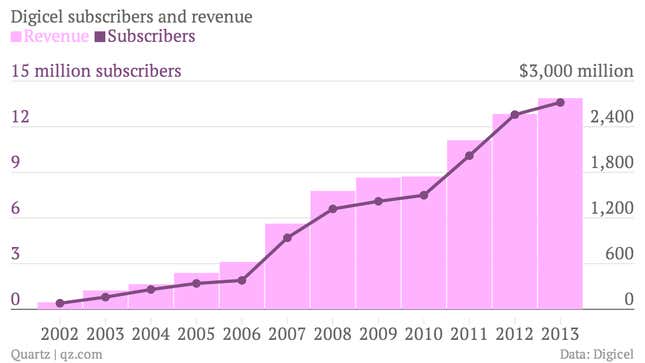

Digicel has enjoyed a spectacular run. Revenue has expanded by an average of 36% per year in the 11 years that it has been in operation. But Digicel’s sprint is coming to an end. With no big acquisitions or new countries to invest in, subscriber numbers are stagnating.

In 2013, only a handful of countries, such as Cuba and North Korea, remain badly served by mobile operators. Myanmar, a big prize, recently opened up to outsiders but Digicel was outbid by Qatar Telecom and Norway’s Telenor. The Bahamas will soon invite bids to break its monopoly but with a population of less than 400,000, it is a minnow.

The days of boosting growth by entering new markets are over, says Delves. Digicel must now find a way to get its 13.6 million users—many of whom live in some of the world’s poorest countries—to spend more.

Moving, last and first

In the past, Digicel learned about rolling out networks from Bharti Airtel, an Indian telecoms giant that successfully expanded into Africa, and about integrating acquisitions from Cemex, a Mexican cement company that grew into a world leader via a series of takeovers. ”There’s a term I like to use called ‘last-mover advantage,'” says Delves. “We look at what has happened elsewhere in the world and learn from that.”

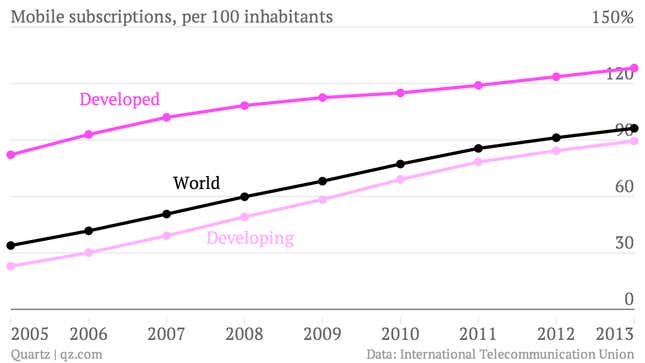

But Digicel’s future path will be instructive for other telecom companies. In 2014, there will be more mobile subscriptions than human beings on earth, according to the International Telecommunication Union. As fewer people remain unconnected to mobile networks, operators from Asia to Africa to Latin America must figure out how to make more money from their existing subscribers rather than simply expanding into more territories or winning over customers from rivals.

A sporting chance

Digicel’s future growth now rests on three pillars. The first and most important is internet access. Digicel has rolled out 4G mobile broadband in most of its markets, ahead of many developed nations. Yet mobile data is hard to sell in poor countries, as Quartz has explained on previous occasions. These countries tend to have lots of pre-paid users who are unwilling to buy expensive data plans, or to buy access to data at all.

Digicel’s solution is to offer tailored data packages. One example is a “day pass”, which in Jamaica, for example, costs one US dollar for a day’s worth of internet usage, within limits. Another is a “social media package”, which lets users access only Facebook, Twitter and a handful of other sites. Digicel is also pushing cheap smartphones, the price of which has fallen dramatically in recent years.

The second pillar for Digicel is mobile money—letting people transfer money and make payments via cellphones. This has been a massive success in Kenya, but less so in other parts of the developing world. Digicel thinks it can make a fist of it in Haiti, a desperately poor country with a large population and abysmal banking system. In the aftermath of the 2010 earthquake that destroyed what little infrastructure Haiti had, Digicel launched TchoTcho, which Haitians now use to transfer nearly $1 billion a year.

It has also invested in a company called Boom, which allows cross-border transfers through a complicated system that lets members of the Haitian diaspora control the cash in US dollars while their relatives back home withdraw it in Haitian gourdes. Flint, another company it invested in, is working on mobile payments, which Digicel thinks could be useful in some of its more developed markets such as Barbados or the Cayman Islands.

The third pillar of Digicel’s business model is an unlikely one. The mobile network is deeply involved in Caribbean sports. It was an early sponsor of world’s fastest man, Jamaica’s Usain Bolt, signing him on in 2004. It is also the main sponsor of the West Indian cricket team. And it owns the Caribbean Premier League, a Twenty20 cricket tournament based on India’s wildly successful Indian Premier League. The reason for this interest in sports is tied to Digicel’s first driver of growth, data. Since the company owns the rights to the matches, it can sell clips for consumption on mobile broadband. That fuels daily data usage, which fuels growth, says Delves.

With data, money transfers and cricket, Digicel may be on to a winning combination. If it works, the ends of the earth may just become a model for the rest of the world.