After freezing up last year, the market for Chinese internet IPOs in the US has quietly begun to thaw, with another important deal expected to price this week. Autohome, the biggest used car sales website in China, and probably the world, is seeking to raise $125 million on the NYSE, in an IPO that would value the business at around $2 billion.

Chinese internet IPOs in the US were booming back in 2011 as investors leapt into just about any play on China’s emerging middle class. But in 2012, the bubble burst after short sellers alleged that high-profile, offshore-listed Chinese companies like Sino-Forest and Universal Travel Group were actually frauds.

Now, as US regulators are enforcing stricter regulations and the demand for IPOs has rebounded, Chinese internet companies are feeling brave enough to come back to the US markets again. Investors have flocked to recent IPOs like Chinese lottery site 500.com (up 30% since its IPO) and classifieds site 58.com (up 21% since its IPO).

But with all of the recent successful floatations, it’s easy to forget that foreign-listed Chinese internet companies all use ownership structures that are convoluted at best—and they may even be possibly even illegal under Chinese law.

China restricts foreign investors from owning businesses in strategically important sectors, including finance, telecommunications and the internet. To get around this, Chinese internet companies such as Autohome use ”variable interest entity” (VIE) structures to access US markets. Essentially, the VIE structure means when you buy shares in the US listing of a Chinese internet company, you’re not actually buying a piece of the underlying business, but only a piece of the contractual rights to its profits and control over management, which lawyers have warned might not even be valid.

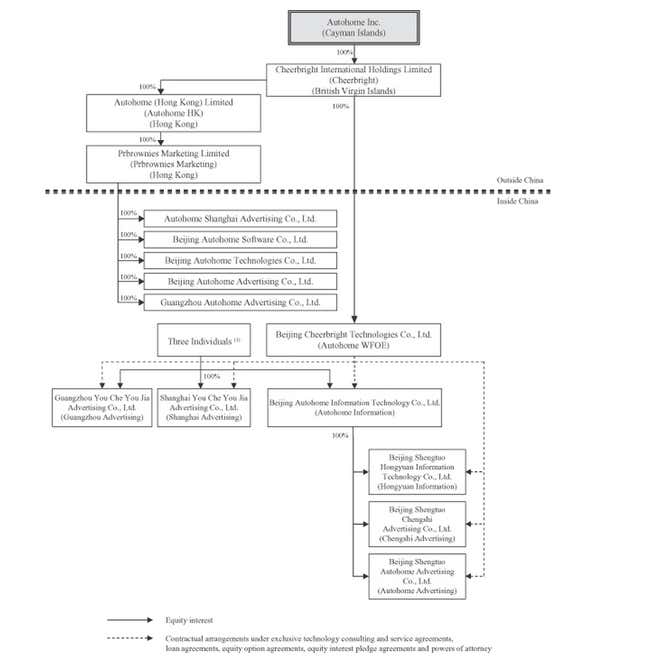

In the case of Autohome, the business being offered on the NYSE this week is actually a holding company based in the Cayman Islands, which controls the underlying assets through equity interests in a bewildering array of subsidiaries in the Virgin Islands and Hong Kong, which in turn hold contracts with entities and executives on the ground in mainland China.

The Chinese government has turned a blind eye to complex and opaque VIE structures in order to keep foreign investment flowing, but there’s no guarantee that this won’t change. China’s highest court ruled in October last year that VIEs used by a Hong Kong based firm to invest in a Chinese bank were void, creating uneasiness among lawyers. The uncertainty makes for bigger risks than the average emerging market stock bet; the Autohome prospectus (p.27), for instance, warns that a change in interpretation of VIEs by the Chinese government could expose the holding company to “severe penalties” and even force it to relinquish its assets.

About half of the 200 Chinese companies listed in the US employ the VIE structure including well known companies such as Baidu, as well as the Hong Kong-listed internet giant Tencent. Expect the VIE structure to get even more scrutiny ahead of the highly anticipated IPO of Alibaba, China’s biggest e-commerce company, which is likely to list in either Hong Kong or New York in the next year or so.