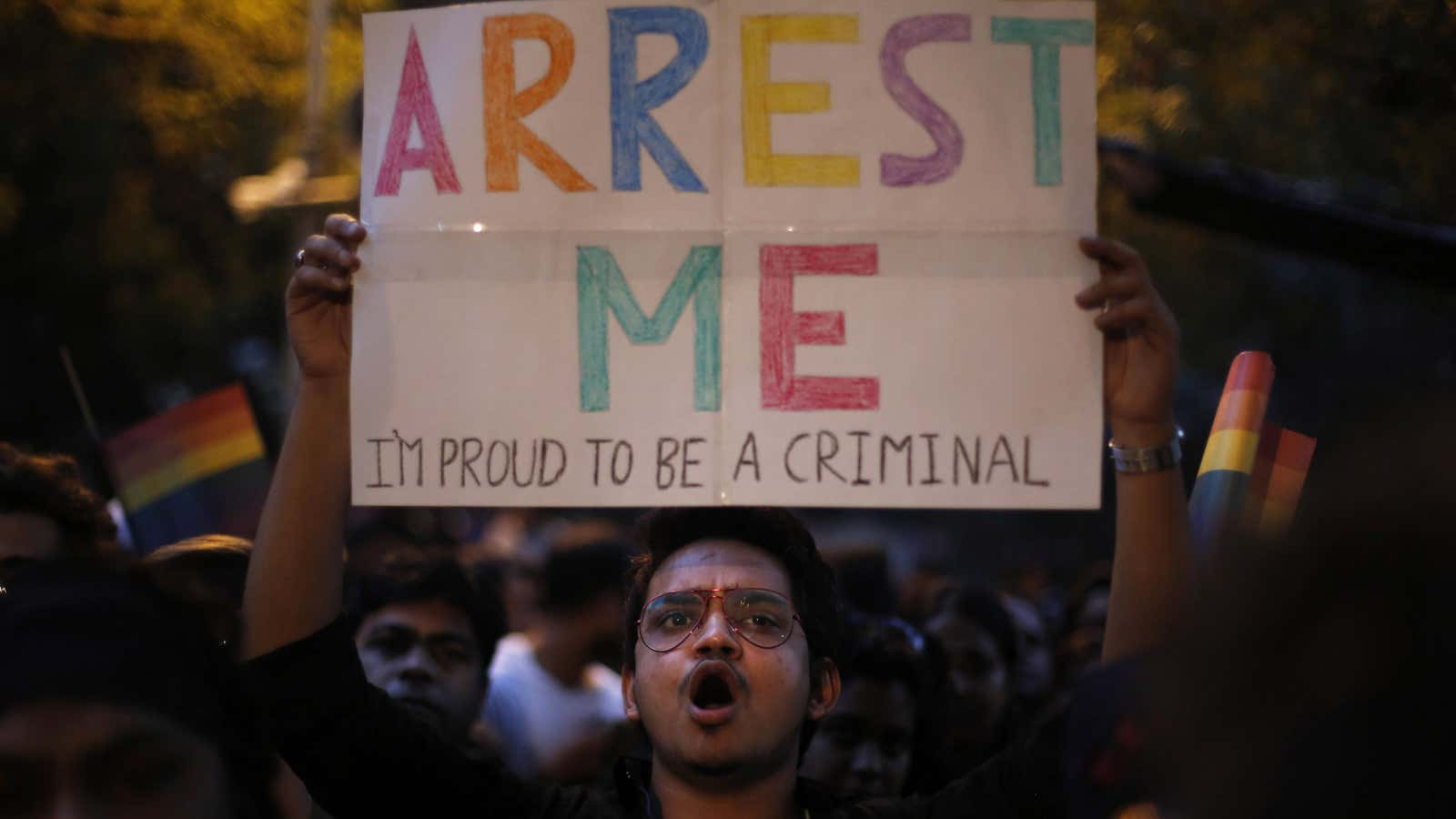

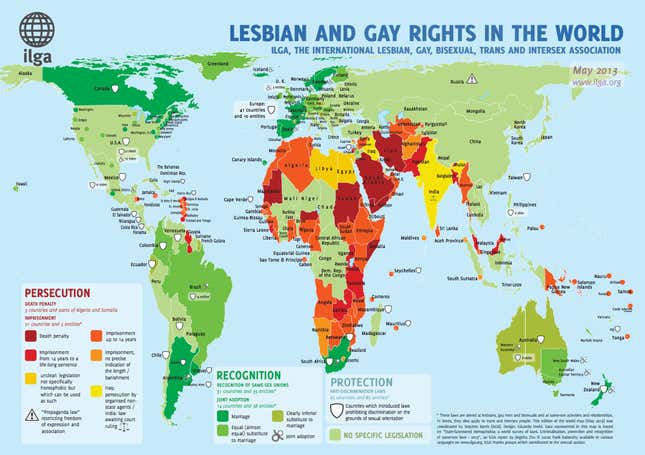

When India’s supreme court effectively re-banned gay sex earlier today, it set aside the ruling of one of its own high courts in favor of a law imposed on India by its British occupiers in 1861. That means it has now re-joined 75 other countries that explicitly punish gay sex with imprisonment. Here’s a look:

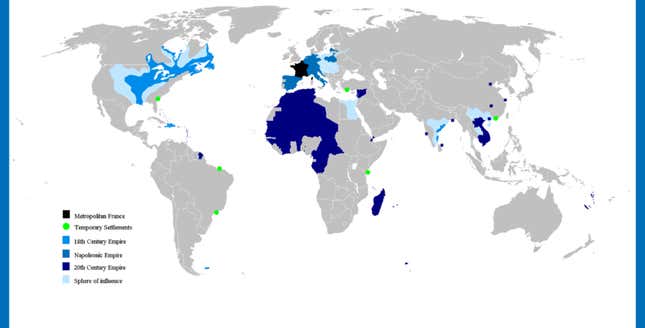

What do many of these countries have in common? More than half were former British colonies:

In fact, the law that India’s supreme court just upheld is one of the most resilient relics of the British Empire. Known as Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code, it imposed Victorian values on what colonial rulers viewed as unpardonable tolerance toward homosexuality throughout their empire. The British instituted versions of Section 377 in colonies all over the world (pdf, p.5). India’s ruling today brings the tally to 42 out of 52 British Commonwealth countries (pdf, p.3) in which the law is still on the books.

But was it just the British? You might notice that a lot of the other countries from the map above where homosexuality is illegal were French colonies:

And many Dutch, Portuguese, Spanish and Belgian ex-colonies have high penalties for gay sex too. However, in these cases colonialism isn’t the culprit. Nearly all of the non-British former European colonies with stiff penalties for homosexual relations instituted them after independence.

That’s probably because the French Revolution banned religious courts, which had previously handled sodomy. This policy spread to the Netherlands in 1811 when France invaded the country. Throughout the 1800s, Spain, Portugal, Belgium and Italy all decriminalized sodomy (pdf, p.22), as Douglas E. Sanders, a professor emeritus at the University of British Columbia, explains.

A more obvious factor keeping homosexuality illegal in many of these countries is Islam. Take for instance the countries that punish gay sex with death: Mauritania, Sudan, Saudi Arabia, Iran, Yemen, and parts of Nigeria and Somalia. Some—Nigeria, Sudan and Somalia—inherited British colonial anti-gay laws. But they too instituted the death penalty long after independence—most in the last 40 years—in line with Islamic sharia law. Many of the other 76 countries with severe anti-gay laws are also Islamic states.

India, however, isn’t. And before the British invasion, it was much more tolerant of homosexuality. So why would India and so many other ex-colonial countries cling so tightly to the moral whims of Victorian Englishmen that were never their own?

One reason might be that morality codes give governments a way to build a national identity around shared values, often as a foil to permissive Western countries. But a more prosaic one is that anti-gay laws are also a handy way to fortify state control (as is now happening in Russia).

What’s more, they always have been. Section 377 originated from a 1536 English law instituted by Henry VIII. Legally speaking, it shifted the law from church courts to secular ones. In practice, it let Henry accuse Catholics of rampant sodomy, sullying the Papacy’s divine authority, argues Sanders. That turned out to be sufficient pretext for Henry to justify seizing monastic properties, claiming a huge portion of England’s landed wealth for the state.