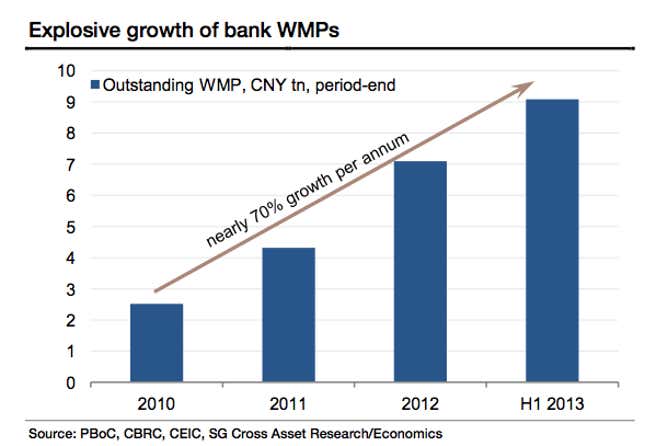

For years now, economists have worried that China’s debt has pushed it to the brink of financial crisis. But if China is insolvent, why haven’t there been any big defaults yet? Here’s why: China’s shadow lending system keeps credit pumping to insolvent companies, so no one can tell that they’re bankrupt. Those loans take place off bank balance sheets, funded largely by retail banking customers via wealth management products (WMPs), which offer a higher return than the government-set deposit rate.

Why do people keep pumping money into the shadow system’s risky loans? Because many assume Chinese banks, which distribute WMPs, guarantee them. The fine print on most WMPs, however, says they don’t. Because there haven’t been any big defaults so far, no one knows who’s actually on the hook.

But that could become clearer, thanks to a huge coal company called Liansheng Resources Group that just declared bankruptcy with 30 billion yuan ($5 billion) in debt. Restructuring its operations may require it to default on debt to investors.

In particular, what happens with Jilin Trust—one of those financial intermediaries that, because they’re largely unregulated, keep the shadow lending pumping—will be instructive.

From late 2011 to early 2012, Jilin Trust sold 1 billion yuan worth of investment products backed by loans to Liansheng, none of which was guaranteed by collateral, as the Financial Times reports (paywall). China Construction Bank, one of China’s biggest and most reputable banks, distributed some of that investment product to its retail customers as WMPs, offering an attractive 9.8% annual return.

The first tranche of that will come due soon. If Jilin Trust can’t pay, will CCB compensate its WMP investors, or will they have to accept losses?

Either scenario risks triggering a financial crisis, particularly given how reliant on ever-increasing liquidity injections China’s financial system now is. If a default leaves investors empty-handed, other investors are likely to pull their money from WMPs, sucking vast quantities of liquidity from the system. Expect a rash of defaults like all the other companies like Liansheng that have been paying off debts with credit.

If the government prods banks to compensate investors, that effectively forces banks to count WMPs as loans, which they currently don’t. Banks will therefore stop issuing WMPs, causing a seize-up like the scenario explained above. More worrisome still, bringing those loans onto bank balance sheets will make it impossible for many banks meet loan-to-deposit ratio requirements. Unlike in the US, Chinese depositors have no deposit insurance. If depositors think banks are short of cash, it could spark a bank run.

Bankruptcies like Liansheng’s are an inevitable consequence of deleveraging, something China’s leaders say they want—but only gradually. The Jilin Trust episode may tell us whether they still have enough control over the system to make that happen.