Until recently, it was impossible to make any real money as a baseball player—or any other professional athlete—in Cuba. Under Fidel Castro, sporting salaries and the reward they represent for individual excellence were regarded as anti-socialist. Athletes, thus, were regarded as state employees, just like teachers or agricultural laborers, and were paid accordingly. Taking your skills abroad was off limits and illegal. (Orlando “El Duque” Hernandez famously left on a sailboat in 1998 with a group of ballplayers and docked in the Bahamas.)

But the wage disparity between Cuba and the rest of the baseball world has forced reform. Official data on athletes’ wages in Cuba is undisclosed, but they are quoted in the media at around $10-$20 a month. In In Major League Baseball (MLB) in the US, the average monthly salary at the worst-paying club, the Houston Astros, was $68,000.

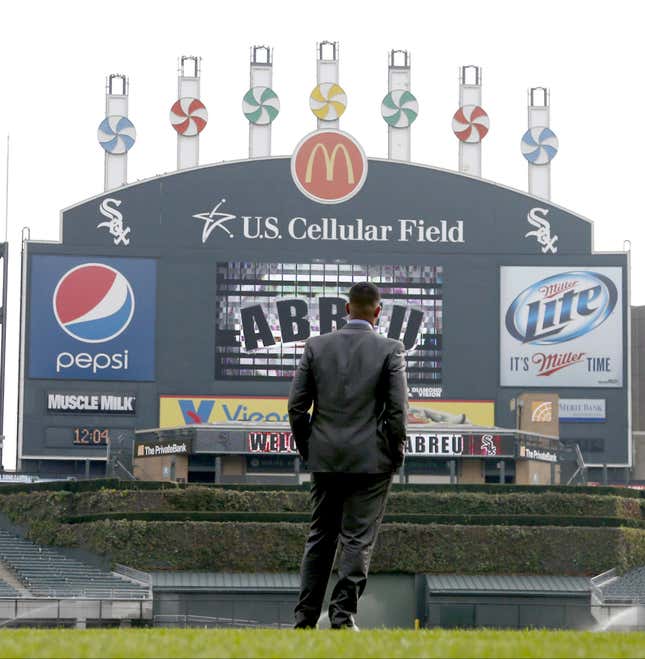

And so the defections from the Cuban National Series to the MLB continue. Most notably, Aroldis Chapman received residency in the tiny European country of Andorra en route to a $30 million contract with the Cincinnati Reds in 2010, and Yasiel Puig received $42 million from the Los Angeles Dodgers via a residency from Mexico. The final straw for the Cuban authorities was Jose Abreu’s signing with the Chicago White Sox for $68 million in October. In the history of sporting transfers, these are among the most politically charged. Footballer Luis Figo might have had a pig’s head thrown at him when he transferred from Barcelona to Real Madrid, but he did not have to seek residency elsewhere.

Faced with a player exodus, the Cuban Baseball Federation has recognized baseball as a profession, doubled the basic wage and provided financial incentives for award-winners. It now also permits players to sign contracts with foreign teams without defecting, provided that they remain available for the domestic season, which runs between November and April. The authorities hope that Cuban players will not head en masse for leagues in Japan and Mexico, but that the liberalizing measures will give them reason enough to stay and slow the talent drain from in the National Series. Similar concessions were granted to Cuban boxers, whose access to international fights and wages have been loosened.

The MLB, however, is still out of bounds. The Cuban authorities require athletes to pay taxes on overseas earnings, while the US trade embargo on Cuba prevents money exiting the US for that country. There is heavy irony at play here. The major sports leagues in the US are more egalitarian than their equivalents elsewhere in the West. Although salaries at the very top of the MLB, NHL, NBA and NFL are huge—the average annual New York Yankees salary is north of $7 million annually—the leagues have all taken steps to maintain their competitive balance, in a way that Castro might approve. The NHL has a fixed salary cap whereby each team can only spend a proportion of the total revenue of the league in the previous season. The NFL has the same system, but also includes a minimum spend, too. The NBA also has a cap, but it is a more permeable one: teams are allowed to exceed it in order to keep hold of players that they had under contract before the agreement was signed.

The rules governing the burgeoning Major League Soccer are tighter still, especially when compared with the liberalism of top football leagues in Europe. The MLS proscribes a set squad size, a cap on the total wage of the team, and also on remuneration of individual players, with the exception of one “designated” player, a loophole that permitted David Beckham to play for LA Galaxy, despite his exorbitant wage demands. In the Premier League, Serie A, La Liga and the Bundesliga, teams operate without any of these restrictions.

There is little consensus on whether salary caps work, partly because there is also disagreement about what constitutes competitive balance. How many different teams need to win a competition in a decade in order for it to be considered exciting? Is the identity of the winner even reflective of the strength of a tournament? In Cuba, these are questions for the future. The first concern is keeping hold of the players that draw the fans to the ballparks. The irony is that the model for the Cuban authorities—the league in which all top baseball players want to play but which keeps tight control over its team activities—the MLB—remains a hostage to political fortune.