This has been a particularly rich year for internet hoaxes, but no less rich for the hoax’s less malicious but equally damaging cousin: the inaccurate report that goes viral on social media before the accurate version has a chance to catch up. And so it’s apt that this year’s last “oh, that’s not exactly true” story (or maybe not the last—tomorrow is another day, after all) is about social media: The “Facebook is dead and buried” story, which was retweeted and rewritten with much enthusiasm.

Here’s what happened. A British academic studying social media found that young people use lots of new-fangled services, such as Instagram, because their parents are on Facebook. “What we’ve learned from working with 16-18 year olds in the UK is that Facebook is not just on the slide, it is basically dead and buried,” Daniel Miller of University College London wrote at The Conversation. What a great quote! No wonder if was all over the internet in two microseconds.

Unfortunately The Conversation, which promises “academic rigour, journalistic flair” on its masthead, this time delivered more of the flair than the rigor. The BBC’s Rory Cellan-Jones looked into the claims and found that the results came from a small, localized area and not from an “extensive European study,” as the Guardian put it in its write-up. Indeed poor old Miller, who wrote the original post, has written an extensive explanation in which he says, twice, that it would be nice if the final study were to go viral rather than an interim blog post. Sorry, Professor Miller—that’s social media for you.

Inevitably, the story has therefore become more about the pitfalls of academics writing for the internet than what’s actually happening with social networks. And what is happening? As it turns out, a Pew report out today from the other side side of the Atlantic explains rather nicely: People young and old are indeed signing up to networks that are not called Facebook. But they are not leaving Facebook.

Social networking is not a zero-sum game. Just as it is possible to have several groups of friends, or several sets of interests, or even different email accounts, it is conceivable that free-thinking individuals will spread out their interests across sites that offer them different things. (One of the problems with Google+, for instance, is that it isn’t substantially different from Facebook, though Google is still determined to overcome that.)

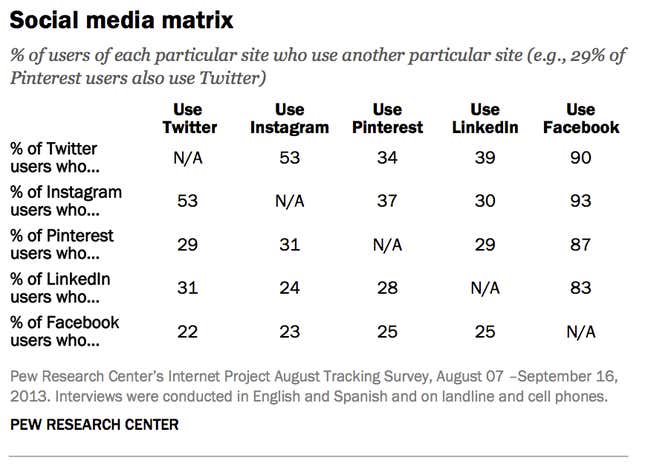

The full Pew report (pdf) has plenty of little gems, but here’s the very best, a “social media matrix” that shows what percentage of members of one network are also on another. Memorize it.