The cold air pushing toward America’s heartland is of a duration and magnitude rarely seen since record-keeping began in the 1870s. In Minneapolis, forecasters warned that all-time wind chill records could be broken, with a stunning -65ºF predicted for Monday morning.

As the record-setting cold spreads across the US, brace yourself for this conversation:

Your friend: “Sure is cold outside, amirite? Minneapolis is as cold as Mars right now. Crazy, huh? So much for that whole global warming thing, eh?”

You: “Well…”

In fact, despite the trolling of Donald Trump and other climate change deniers, global warming is probably contributing to the record cold, as counter-intuitive as that may seem. The key factor is a feedback mechanism of climate change known as Arctic amplification. Here’s how to explain the nuts and bolts of it to your under-informed family and friends:

Snow and ice are disappearing from the Arctic region at unprecedented rates, leaving behind relatively warmer open water, which is much less reflective to incoming sunlight than ice. That, among other factors, is causing the northern polar region of our planet to warm at a faster rate than the rest of the northern hemisphere. (And, just to state the obvious, global warming describes a global trend toward warmer temperatures, which doesn’t preclude occasional cold-weather extremes.)

Since the difference in temperature between the Arctic and the mid-latitudes helps drive the jet stream (which, in turn, drives most US weather patterns), if that temperature difference decreases, it stands to reason that the jet stream’s winds will slow down. Why does this matter?

Well, atmospheric theory predicts that a slower jet stream will produce wavier and more sluggish weather patterns, in turn leading to more frequent extreme weather. And, turns out, that’s exactly what we’ve been seeing in recent years. Superstorm Sandy’s uncharacteristic left hook into the New Jersey coast in 2012 was one such example of an extremely anomalous jet stream blocking pattern.

When these exceptionally wavy jet stream patterns occur mid-winter, it’s a recipe for cold air to get sucked southwards. This week, that’s happening in spectacular fashion.

Climate scientist Jennifer A. Francis of Rutgers University explains this process in a short video (h/t Climate Progress):

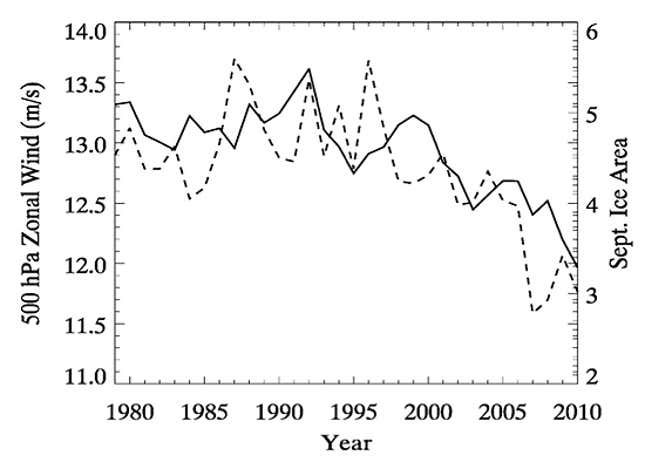

This effect has already been measured with mid-level atmospheric winds in the northern hemisphere decreasing by around 10% since 1990. Not-so-coincidentally, that’s about the same time when Arctic sea ice extent really started to crash.

The solid line is average west-to-east wind speeds midway up the atmosphere; the dashed line is Arctic sea ice extent.

Skeptical Science (the ‘Snopes’ of climate science) has a comprehensive explainer on Arctic amplification and the jet stream, for those that want to dig deeper on the subject. And, as a PSA, is a great-go to resource when situations like this arise.