The great bee die-off in the US and Europe has been known about for a while. A shortage of honeybees, it’s feared, threatens various crops that depend on them as pollinators. But now some research has put numbers on just how bad the bee deficit is in Europe. And the numbers are alarming, to say the least.

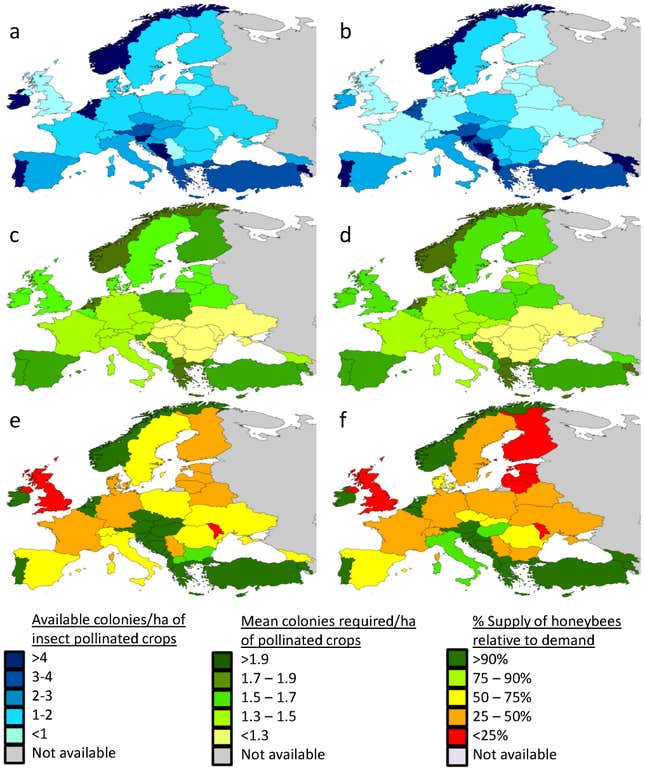

In the study of 41 countries, published yesterday, researchers found that between 2005 and 2010, demand for so-called “pollinator services” grew nearly five times faster than the supply of bees. In the UK, researchers estimate that there are now only enough beehives to meet a quarter of demand. Through a broad swath of Europe, they can meet only 25% to 50%. Overall, almost half the countries studied had bee deficits. “We face a catastrophe in future years unless we act now,” researcher Simon Potts of the University of Reading in the UK, told The Guardian.

Why hasn’t there been a catastrophe already? Because “wild pollinators”—bumblebees, hoverflies and others—have picked up the strain. That’s the good news. The bad news is that scientists have little hard data on wild bee numbers and their pollinating habits. Worse, wild bees may be just as much at risk as honey bees. “Recent studies have demonstrated widespread declines in wild pollinator diversity across much of Europe due to a combination of agricultural intensification, habitat degradation, the spread of diseases and parasites and climate change,” the researchers wrote.

The cause of all this isn’t just the global collapse in bee populations over the past seven years, which scientists believe is due to pesticide exposure and disease. Even as bees have been disappearing, the amount of land converted to agriculture use has soared. Overall, the amount of farmland devoted to growing crops that depend on bees has jumped 300% since 1961, according to the study.

That’s partially a result of the biofuels boom of the past decade. Farmers have rushed to plant corn, canola and other crops that serve as feedstocks for ethanol and biodiesel, to replace fossil fuels. But as farmers clear the land to grow these crops, they remove many of the wild flowers and other plants whose pollen bees collect to feed beehives. Weakened by the lack of food, bees become more susceptible to disease and pesticide poisoning, studies have shown. That contributes to the affliction known as Colony Collapse Disorder, where entire beehives suddenly die. Whether enough bees survive in the future to pollinate food crops depends, in part, on how much land continues to be reserved for biofuel production, the researchers wrote.