The perception of excessive pay not properly linked to performance puts executives—and the boards that sanction their compensation—in the crosshairs of activists, politicians and a wide variety of scolds.

Starting at this year’s annual shareholder meetings, investors in the UK will have a binding vote on company pay policies. This puts more scrutiny on board of directors’ remuneration committees than in the past, when—critics contend—directors were free to rubber stamp compensation policies devised by sycophantic consultants or simply set pay levels by taking the average for their industry and adding on a premium. (Every company, after all, thinks its leadership is above average.)

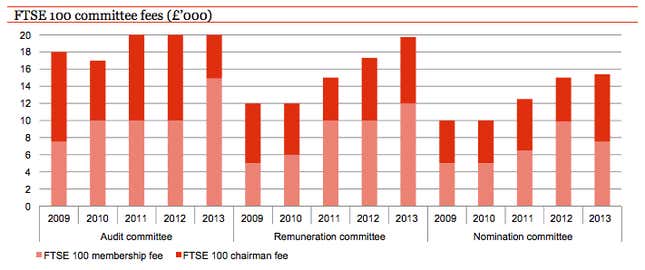

But one result of the increased prominence of remuneration committee members is that, somewhat ironically, the pay they set for themselves is soaring. At FTSE 100 companies, the median fee collected by directors on the remuneration committee (on top of their salary as a board member) has more than doubled over the past five years, according to a new study by PricewaterhouseCoopers. Over the same period, the base fee for directors has risen by 11% overall.

Chairing the remuneration committee is now nearly as lucrative as leading the audit committee, arguably a more fundamental role charged with ensuring the accuracy and integrity of a company’s financial reports. Last year, the median FTSE 100 audit committee chair took home £96,000 ($157,000), while the remuneration committee chair made £93,000. The average board met nine times last year (pdf, p15), with audit and remuneration committees holding an additional five meetings each.

Spiraling directors’ fees is probably not what activists had in mind when they pushed for greater scrutiny of corporate pay policies. But with the average FTSE 100 CEO making £4.5 million a year (and a few executives much, much more than that), paying a handful of part-time directors a few thousand pounds more per year might be worth it, if it attracts higher caliber candidates who supervise pay policies for the top earners more stringently. And as the directors themselves might say: You get what you pay for.