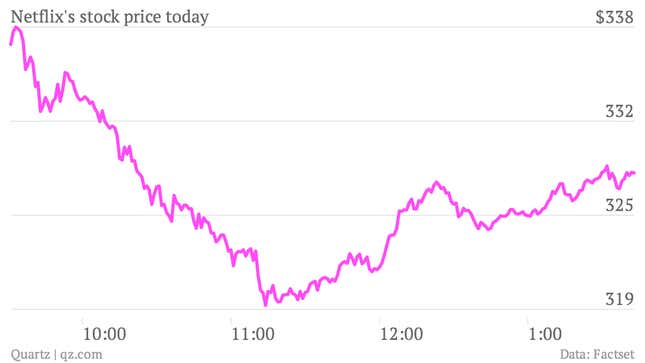

Today, Netflix shares are falling, and one reason for the sell-off is yesterday’s US court decision overthrowing “net neutrality” rules—but investors may be acting prematurely.

Net neutrality is the idea that internet service providers (ISPs) have to treat all data flowing through their networks equally: They can’t, for instance, make Netflix’s streaming videos travel more slowly than web pages from Quartz. The US Federal Communications Commission put in place three basic rules in 2010 to enforce this: ISPs had to be transparent about their approach to network congestion, couldn’t block high-bandwidth users, and couldn’t unreasonably slow their traffic. Yesterday, a federal appeals court overturned these rules after a challenge by Verizon, the top US telecom.

This matters because Netflix takes up about a third of US bandwidth at peak hours. Like other online companies that guzzle traffic (e.g., big sites like Google and Yahoo), it makes money on top of infrastructure built by ISPs, but doesn’t give them a cut of the proceeds beyond standard access fees. AT&T CEO Ed Whitacre speaks for broadband providers when he said companies like Netflix want to “use my pipes free, but I ain’t going to let them do that because we have spent this capital and we have to have a return on it.”

Net neutrality, the telecoms say, makes investments in broadband infrastructure unaffordable. Net neutrality’s supporters worry that without it, ISPs might be able to limit competition, or discriminate against online services based on the type of content, not just how much bandwidth it takes up.

The basic question—one at the heart of a lot of internet issues—is to what extent the internet’s pipes should be considered public infrastructure, like roads, water lines or telephone lines. Such “common carriers” may not unreasonably discriminate against their customers. The FCC doesn’t consider ISPs common carriers but “information services,” exempt from regulation as new, developing technologies.

The federal appeals court said, in essence, that the FCC can only impose net neutrality on the broadband providers if it first declares them common carriers. It could now take that step. The carriers’ allies in Congress have long opposed such a move, but they probably couldn’t force the Obama administration to block it. Congress itself could also put in place—or prohibit—net neutrality rules, although it’s unlikely to do either.

Even failing a common-carriers declaration, net neutrality isn’t buried. Both its opponents and proponents believe the court decision has unintended consequences that will empower the FCC to enforce the essentials of net neutrality without re-classifying ISPs. Even if they aren’t considered common carriers, the FCC is empowered to regulate them under a different statute.

That’s not anyone’s ideal outcome, which might put more pressure on Congress to act. But in the meantime, Verizon can’t be entirely pleased with an outcome that may push the FCC into taking action—and Netflix can breathe a sigh of relief that there are still avenues to protect if from data charges that could wreck its business model.