One of the great mysteries of China’s off-balance-sheet lending craze, which we’ve followed closely for a while, is why people are willing to keep lending money to companies they know essentially nothing about. The short answer is that they assume someone will step in to protect them from any losses. But this may be the year that’s about to change.

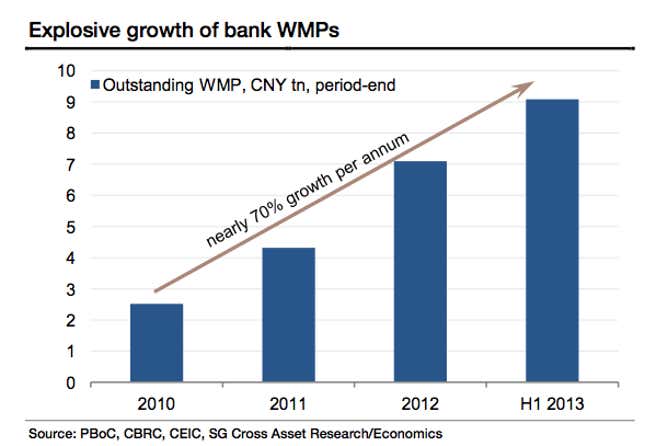

As a reminder, off-balance-sheet lending is when ventures that can’t qualify for a commercial bank loan borrow more-or-less directly from retail investors, via an instrument called a wealth-management product, or WMP. Though WMPs typically reveal little about the underlying assets (and with good reason since many invest in risky ventures), investors haven’t sweated potential losses because they assume someone—the government, the banks that sold them the WMPs, or the trust companies that manage them—will cover any loss. And WMPs pay better interest than a bank account.

However, last month we reported on the looming default of a coal company on loans via a trust-backed WMP. And today reports emerged of another big coal-related default, this one involving Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC), the biggest bank in the world by assets.

The bank reportedly sold a 3 billion yuan ($495 million) high-yield WMP to its banking customers in 2010. China Credit Trust, the trust company that managed the WMP, lent that money to an unlisted coal company, Shanxi Zhenfu Energy Group Ltd.

Come Jan. 31, the trust company will owe 3 billion yuan plus interest to ICBC’s customers. But it looks like the company it loaned to, Zhenfu, is too drowned in debt to cough up the money. China Credit Trust recently informed investors that Zhenfu has 5.9 billion yuan in outstanding liabilities (link in Chinese), including 2.9 billion yuan in high-interest shadow loans, and not enough collateral to pay back ICBC customers.

ICBC is now refusing to use its own funds to repay investors, reports Reuters. And legally, it probably doesn’t have to. But it might have to rethink that refusal.

As one trust company told Sohu.com, the regulations hold trust companies liable for breach of contract if they improperly handle assets. However, investors bear the onus of proof (link in Chinese). Neither trust companies nor banks typically give investors much information. And because this sort of thing has never happened before, most investors don’t demand it. ICBC’s customers might therefore lack sufficient evidence to prove CCT’s guilt.

And unlike CCT, ICBC has a huge brand to maintain, as well as its share price. Leaving its customers high and dry on this product risks costing it in future WMP sales, jeopardizing its profitability.

It wouldn’t just hurt ICBC, though. By the looks of it, lots of other products are struggling too, though less publicly. Banks declined to publish the returns for more than 45% of WMPs (link in Chinese) that matured in 2013, something analysts say is happening because banks are concealing poor returns from investors. Typically, banks pay investors in WMPs with money raised from newly issued WMPs or by offering to roll the expected profit into new, higher-yielding WMPs. Which is easy to do when investors don’t ask any questions. But if they now start asking them, the whole off-balance-sheet lending system might start to unravel.