There’s a problem with today’s voice recognition systems: They’re just too slow. Anyone who has waited in frustration while Siri or Google’s Voice Search “thinks” about even the simplest commands knows what I’m talking about.

The problem isn’t voice recognition software per se, which is more accurate than ever. The problem is that voice recognition is still a challenging enough problem, computationally, that all the major consumer platforms that do it—whether built by Google, Apple or Microsoft with the new Xbox—must send a compressed recording of your voice to servers hundreds or thousands of miles away. There, computers more powerful than your phone or game console transform it into text or a command. It’s that round trip, especially on slower cellular connections, that make voice recognition on most devices so slow.

Update: To clarify, Google has had offline voice recognition since Android 4.1, but it’s still in the experimental phase and isn’t available to non-Google developers of apps. In addition, Scott Huffman, head of the Conversation Search group at Google recently told me that while Android can do some offline processing of voice commands, it’s much less accurate than what Google can accomplish when it sends your voice to the cloud.

Intel wants to process your voice right here, instead of in the cloud

Intel has a solution, says the company’s head of wearables Mike Bell in an exclusive interview with Quartz. Intel partnered with an unnamed third party to put that company’s voice recognition software on Intel mobile processors powerful enough to parse the human voice but small enough to fit in the device that’s listening, no round trip to the cloud required. (Update: That third party is almost certainly Nuance, which is busy licensing its voice recognition software to all comers.) The result is a prototype wireless headset called “Jarvis” that sits in the wearer’s ears and connects to his or her smartphone. (Perhaps coincidentally, Jarvis is also the name of the voice recognition and artificial intelligence software in the Iron Man franchise.) Jarvis can both listen to commands and respond in its own voice, acting as both a voice control and a personal assistant.

Not only is Intel’s voice recognition solution more responsive than those offered by its cloud-obsessed competitors, but it also leads to what Bell calls “graceful degradation,” which means that it works even when the phone it’s connected to is not online.

Voice commands that work even when you’re not connected

“How annoying is it when you’re in Yosemite and your personal assistant doesn’t work because you can’t get a wireless connection?” says Bell. “It’s fine if [voice recognition systems] can’t make a dinner reservation because the phone can’t get to the cloud,” he adds. “But why can’t it get me Google Maps on the phone or turn off the volume?”

Processing voice commands right on the device is one of those trivial but not so trivial innovations. As cloud and Internet of Things journalist Stacey Higginbotham has observed, people won’t want to wait three or more seconds when we command our automated house to “turn on the lights.” For true voice interaction with computers, the kind that involves clarifications and a genuine dialogue, our devices are going to have to respond to our voice just as quickly as a human would—or even faster.

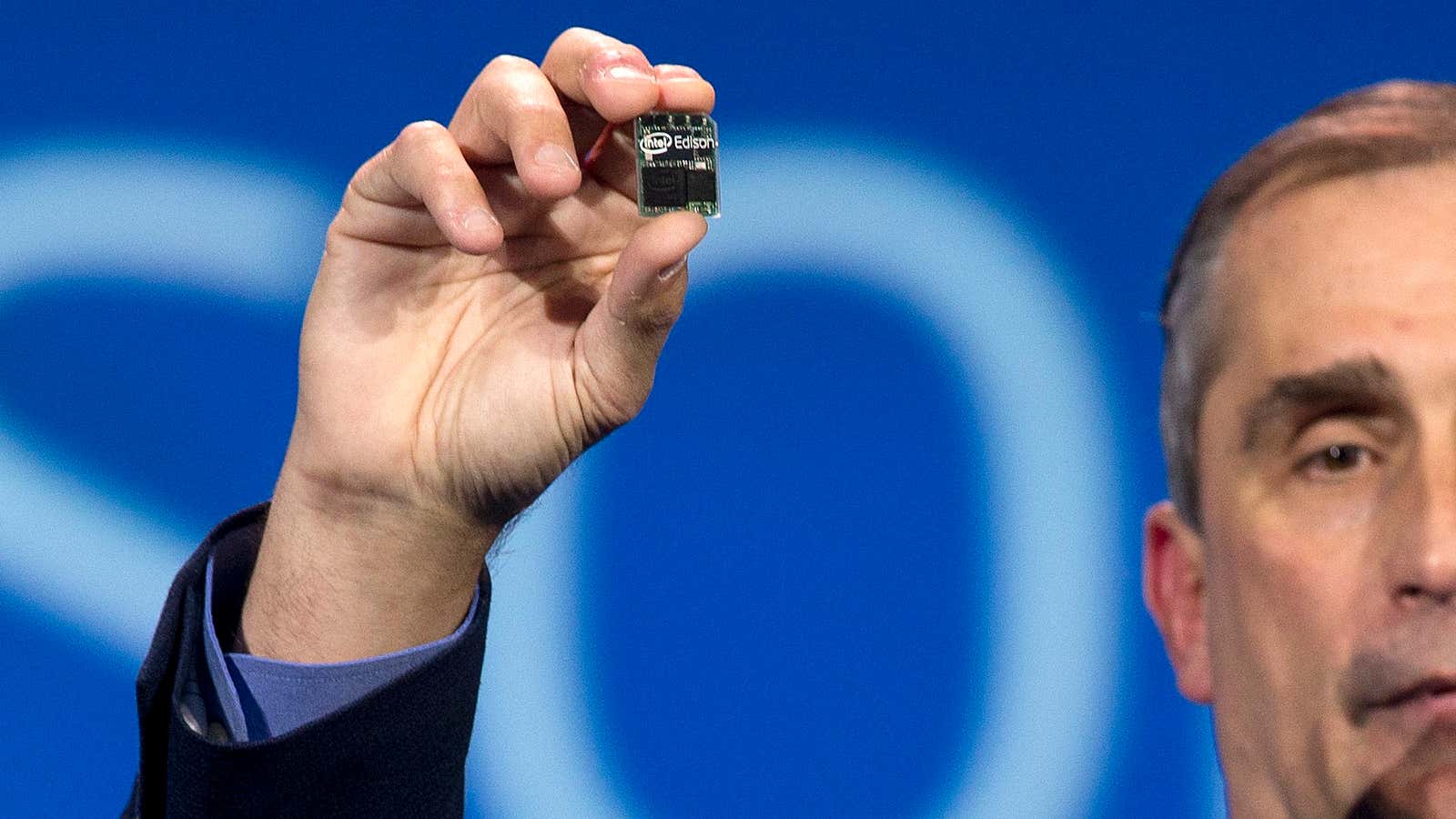

Voice recognition performed right on a computer has been available on desktop computers for several years, but the processors in mobile phones and other mobile or wearable computers simply haven’t been powerful enough to accomplish the same feat until now. As it moves into mobile with products like the just-announced Edison PC-on-a-chip, Intel pitches its expertise in making powerful microchips for servers and PCs as a unique advantage for making the world’s most powerful mobile processors, which are typically much less capable than the ones that are Intel’s bread and butter.

Coming to a phone or wearable near you

Bell says that Intel is working on selling its voice recognition technology to unnamed mobile phones manufacturers, which could allow them to differentiate themselves from Apple and Google’s usual offerings—or the tech could go into phones by those companies.

The result could be voice-recognizing devices with which we can have an actual conversation. That could mean something as simple as telling our phones to “please email Mike,” followed by the phone asking which “Mike” we mean. It will also, inevitably, mean something like the artificially intelligent conversation systems pictured in Iron Man, transforming our computers into something like true personal assistants.