If milk “does a body good,” as the classic dairy farmer ad campaign claimed, then toddler milk—the heavily fortified and increasingly lucrative milk drinks aimed at children more than a year-old—promises to do even better.

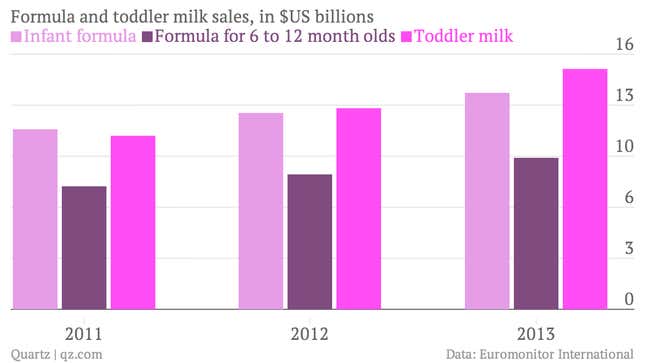

Also known as “growing-up milk” or “GUMPs” (growing-up milk products) by the companies that make them, powdered milk-based beverages for the 1- to 5-year-old set have exploded into a $15 billion business. Thanks to massive global advertising campaigns, they’re now the biggest and the fastest-growing product that formula makers sell.

But health professionals around the world say toddler milks are not only expensive and entirely unnecessary, but could be harming children’s long-term health. Regulating them and how they are sold is the next big battle in the long, acrimonious relationship between the $41 billion-a-year formula industry and global health advocates.

Breastfeeding advocates are winning the long war over infant nutrition

Toddler milk products seem to have sprung up from nowhere in recent years, but their creation can be explained through the formula industry’s controversial past. “Scientific” powdered formulas were so widely embraced that only 25% of US women born in the late 1940s breastfed their infants, down from 70% thirty years earlier. Saleswomen dressed as nurses routinely distributed formula in maternity clinics around the world, and manufacturers flooded clinics in third-world countries with free formula and bottles.

After a landmark article linked powdered formula use to increased disease and malnutrition, particularly in developing countries without clean water, the World Health Organization (WHO) voted in 1981 to recommend banning advertising and marketing of formula for babies under six months, rules that were quickly adopted by governments around the world.

Breastfeeding rates of infants have crept back up. In 2010, 77% of new babies in the US were breastfed. In Hong Kong, the percentage of new mothers opting to breastfeed jumped from less than 20% in 1992 to more than 80% in 2011. The proportion of babies under six months who are breastfed exclusively, meaning they drink no formula at all, are rising worldwide, according to Unicef:

This has been tough on the formula industry. Mothers are “returning to a more traditional parenting technique of breastfeeding their children,” Datamonitor analysts presciently wrote in 2009—a trend that ”presents problems for the baby drinks industry.” Datamonitor suggested the industry focus on “life stage targeting” instead.

That’s exactly what it did. By 2012, growing-up milk sales were the industry’s biggest product.

Creating a children’s “health” product that didn’t exist before

It’s just in the last five years that toddler milk has “become really popular,” Lauren Bandy, an analyst with Euromonitor International, tells Quartz. Now more than “one in three dollars spent on infant formula globally is going on toddler-specific products,” she said.

Toddler milk is sold as a powder and is cow’s milk fortified with vitamins, minerals and a dizzying array of additives, sweetened with sugar or corn syrup, and sometimes flavored with vanilla. (Some kid-tempting flavorings have been known to backfire: Industry heavyweight Mead Johnson Nutrition Co. was forced to pull its chocolate-flavored product off the market in 2010 after US nutritionists complained it was pushing sugary products to kids.)

The milks are sold in cans that look like baby formula, often under similar brand names like Enfamil and Similac, but they do not fall under WHO and most local advertising bans because they target children one year old and up. Their marketing suggests they have the same benefits as drugs or supplements, but they generally are not subject to the same regulatory oversight as medicine.

Companies have pushed their health benefits, 0ften backed up by industry-funded research that has not been corroborated independently:

- Gain “IQ Growing-up milk” touts “nutritionally important ingredients” that “support brain and eye development.”

- Danone’s Aptamil promises to support “toddlers’ optimal growth in these vital first few years, through clinically proven enhanced immunity with reduced risk of infections in addition to optimal brain and visual development.”

- Nestle’s Nido “pre-school milk” contains “Prebio³, a unique blend of fibre that helps maintain a regular digestive system.”

- One of the biggest buzzwords is “DHA,” or docosahexaenoic acid, a substance that occurs naturally in breast milk.

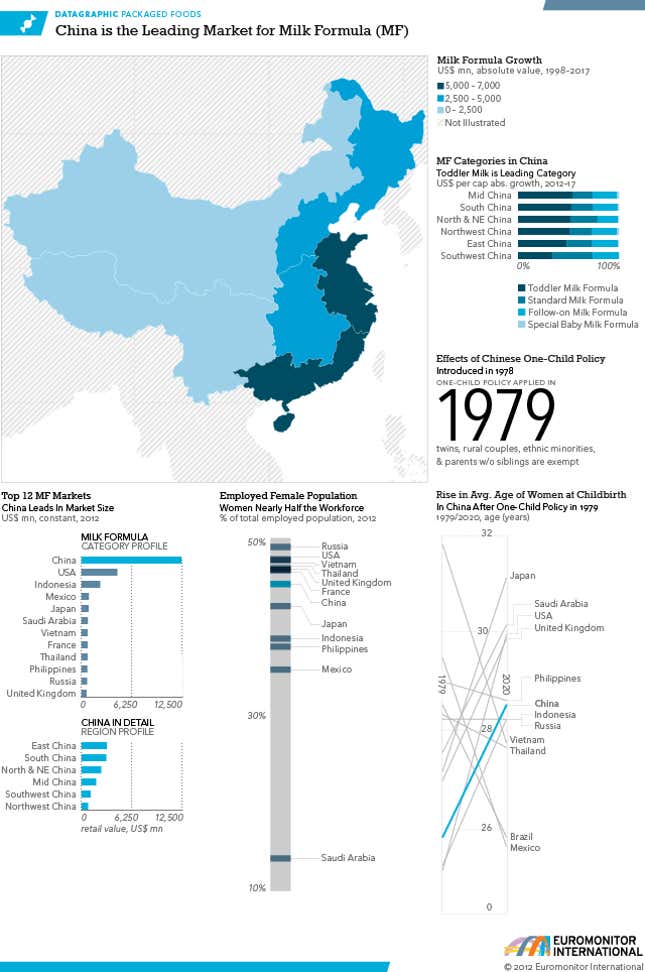

Health-care professionals say formula makers have been incredibly savvy in creating a new market after being banned from advertising their mainstay product. For instance, they’ve perfectly targeted the millions of parents of only children in China, according to Agnes Marie Tarrant, an infant-feeding expert and associate professor at the University of Hong Kong. These parents are more apt to buy special products for conditions like being a “picky eater,” which tend to naturally resolve themselves over time. The West’s “helicopter parents,” who pepper parenting discussion groups with toddler milk questions, are another target market.

“All these things are made for neurotic parents,” Tarrant told Quartz.

The advertising of products that look like formula, but are for older kids, is undermining the hard-fought curbs on formula marketing for young babies, breastfeeding advocates complain. “All mothers know that breastfeeding is good, but their husbands, their mothers-in-law are exposed to this aggressive marketing,” said Patricia Ip Lai-sheung, vice-chairman of the Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative Hong Kong Association. These ad campaigns have been so good that if a breastfeeding baby “does not appear to be perfect, they will blame the mothers for not giving it formula.”

Selling toddler milk to Asia

The US and EU buy billions of dollars a year of these products, but the most important market is Asia. The growth of these products has been “driven by rising demand from Asia Pacific, notably China,” said Euromonitor’s Bandy, where “the consumption of milk formula is almost a craze.” Sales of toddler formula in China have tripled in the last five years, she said, and the country accounts for more than 40% of global toddler formula sales. Indonesia, Vietnam and Thailand are also big consumers. “Rising incomes means that parents are able to buy milk formula not only for their infants, but also for their toddlers—products that were unaffordable for previous generations,” she said.

The marketing of these products is particularly eye-catching in Asia, where they’re sold as miracle foods, capable of helping young toddlers become over-achievers, by playing violins and lifting barbells:

and helping older children outperform their peers in a hyper-competitive school environment:

[protected-iframe id=”3d952bc114da931a4566cfb3072ed7c4-39587363-51034579″ info=”http://client.joy.cn/flvplayer/1129929_1_0_1.swf” width=”480″ height=”400″]

An Abbott Laboratories product, Grow, targets school-age kids who are juggling a full menu of activities. “Not only do they have school and homework, there are also enrichment classes, swimming, ballet and music lessons that they have to rush to” one Singapore ad says.

“As a nutritionist and a mother, I will always give what is best for my baby,” a lab-coated woman pledges in a recent ad in Chinese for Nestle’s Nan H.A. 3, before she hugs a toddling girl, and hands her a sippy cup.

Why kids don’t need what’s in toddler milk

After the age of six months, doctors almost universally agree, babies can start to eat solid food. By 12 months they can consume cow’s milk, although the WHO recommends breastfeeding until at least 24 months. Toddlers don’t need any special beverages or supplements if they’re eating a healthy diet.

Manufacturers say that is where they fit in.

“Ideally, a balanced diet ought to provide all the essential nutrients required by young children,” Meike Schmidt, a spokeswoman for Nestle, tells Quartz. “However, scientific studies and dietary surveys in EU countries show that the diets of young children do not always meet the necessary nutritional requirements for this age group.”

“It is one thing to know what an ideal diet for a toddler should be, but often quite another matter to get a young child to consume all those foods on a consistent basis,” says Chris Perille, a spokesman for Mead Johnson Nutrition. “A science-based milk product containing essential nutrients that is also considered palatable—or is even sought after—by a child can effectively fill certain dietary gaps and provide parents reassurance that their children’s nutritional needs are being met.”

Abbott Laboratories said these products are “for children who are at nutritional risk or need to supplement their nutritional intake.” Danone, the other major manufacturer of toddler milks, did not respond to requests for interviews.

There has been little global testing of growing-up milks and their claims, but a growing number of national and regional studies question their use. One British consumer group found that toddler milk has less calcium and nearly double the sugar of regular cow’s milk, at more than four times the cost. The European Union’s food-safety agency said in October that growing-up milk “does not bring additional value to a balanced diet in meeting the nutritional requirements of young children in the European Union.” Australian researchers say the advertising for them constitutes “de facto infant formula advertisements.”

There is little evidence that adding “untested novel ingredients into fortified milk for older children will offer any benefit at all,” according to First Steps Nutrition Trust (pdf).

Often, these drinks contain much higher levels of protein than breast milk or cow’s milk, health advocates say, which undercuts demand for healthy food. “When you drink a lot of formula milk, your appetite is not so good,” Ip said. That makes parents think their kids are picky eaters, she said, which then leads them to feed them more toddlers milk. These companies “are trying to solve problems they are creating,” she said.

In China, the most important market for toddler milks, parents know little about criticism of these products. After Richard Saint Cyr, a family doctor in Beijing, wrote a column last year in Chinese calling toddler milks an unnecessary invention aimed at making more money out of parents, he said received “shocked” responses from parents. They’d “never heard these concerns before, since their doctors and pediatricians have told them to use toddler formula,” rather than feed their children potentially unsafe local milk, he told Quartz.

Toddler milk as the new battleground

Some countries are now considering tough legislation aimed at toddler milk companies, particularly the Philippines and Hong Kong.

In October of 2012, Hong Kong authorities issued a draft of a new marketing code for these products, which would ban manufacturers from “any promotional activities involving formula milk and formula milk-related products” aimed at children under three years old, and put strict limits on the way these companies can conduct education.

One trade institute argues the code Hong Kong proposes is so restrictive that junk food manufacturers are more free to promote products to parents and kids under three than the toddler milk companies are. And if governments in Asia can’t guarantee the safety of local food, they shouldn’t be limiting parents from importing formulas, attorney Lawrence Kogan, who runs the institute, tells Quartz. “What can parents do if they can’t buy local produce?” Kogan said. “These products can fill that gap.”

Kogan also believes the Hong Kong code violates World Trade Organization rules, in part because it limits companies from using trademarks that are their intellectual property and imposes unnecessary obstacles to trade. The strict laws could spread, he argues.

“Breast-hugger activist groups in Asia largely view this legislation as a model for the world,” he wrote recently.

Ivy Chen and Jennifer Chiu contributed reporting.