The European Central Bank has little room to maneuver, with its benchmark policy rate set at only 0.25%. But the odds that it will cut this rate to zero at its next meeting, on Feb. 6, just jumped.

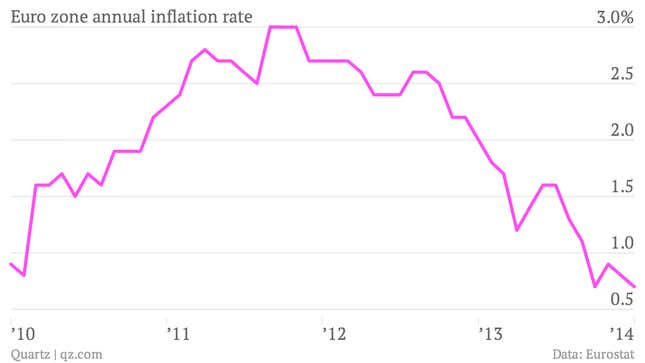

Euro zone inflation (pdf) in January was weaker than expected, with prices rising by only 0.7%, matching the slowest rate in more than four years. The last time inflation slowed to the current level, in October, it prompted the ECB to cut rates at its following meeting.

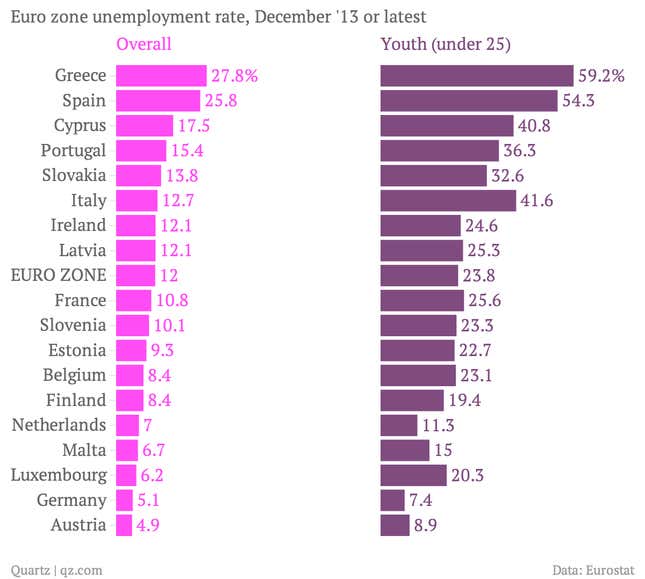

The euro zone also got its latest reading on unemployment today (pdf). The jobless rate in December was 12%, in line with expectations and little changed over the past year (it was 11.9% in the previous December). Youth unemployment, the bane of the euro zone, edged down to 23.8% in December, from 24% the month before, but it too is more or less flat versus a year earlier.

In itself, stubborn unemployment is not enough to prompt a rate cut by the ECB. But the lack of improvement in the labor market combined with falling inflation will make things uncomfortable for the central bank. The last time it cut rates president Mario Draghi cited ”further diminishing underlying price pressures” as the rationale. The key economic stats are almost identical now to what they were then; should we expect a similar response from Draghi & Co?

A decision to cut rates would push the ECB to the limits of conventional monetary policy. Since rates could go no lower than zero, the bank would need to fight further economic weakness with unorthodox tools, like quantitative easing. But its means will be limited. While the ECB has already flooded the banking system with more than one trillion euros in a few rounds of cheap loans, outright bond-buying like in the US, UK and Japan is usually seen as a step too far (paywall). Germany is dead set against it, and the opinion of the euro zone’s biggest creditor obviously carries a lot of weight.

“The low inflation figures could prompt the European Central Bank to add more stimulus in the near future,” says Azad Zangana, an economist at Schroders, in a research note. “However, the ECB has largely exhausted the tools at its disposal, or at least those tools that Germany is willing to tolerate.”