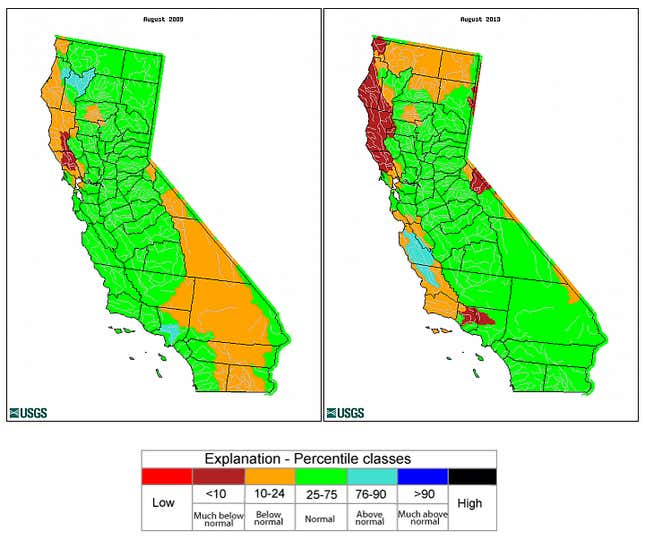

Heavy rains in California in recent days have partly alleviated the drought that parched the state in January. The dry spell is merely exacerbating a long-developing problem in northern California, however: The huge volumes of water used to grow marijuana, as well as the noxious fertilizers and pesticides gushing into streams, are pushing local watersheds to their breaking point.

“Marijuana cultivation has the potential to completely dewater and dry up streams in the areas where [cannabis farmers are] growing pretty extensively,” Scott Bauer, a biologist with the California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW), tells Quartz. He describes encountering waterless streambeds littered with dead fish.

Pot is not the only water-guzzling business that’s booming in the Emerald Triangle, as Humboldt, Mendocino and Trinity counties are known. Wineries are too. The problem is that the government treats them differently, says Gary Graham Hughes, executive director of the Environmental Protection Information Center (EPIC), a non-profit group.

The paradoxical status of marijuana in the US—it is legal to grow and sell in some states, but remains illegal under federal law—makes it hard to regulate. In theory, Californian state or local regulators should be able to set environmental standards for cannabis cultivation, the way they might with grapes or timber. But the federal government won’t let them. As a result, growers enjoy unregulated use of water, and the resulting easy profits have helped attract operations that are increasingly industrial in scale—and run by growers who are unrepentant about sucking the Emerald Triangle dry.

Pot is central to the local economy…

Pot is one heck of a valuable crop. The farm value of cannabis grown in California for local consumption is probably between $2.5 billion and $5 billion a year, according to Dale Gieringer, an economist at California Norml (CA Norml), a pro-legalization non-profit, assuming a price of $2,500 per pound. The out-of-state export market could be even larger, he says.

It’s especially valuable for the otherwise downtrodden Emerald Triangle economies. In Humboldt, occasionally called the Silicon Valley of weed, some 4,000 commercial growers generate at least $400 million in annual sales. That compares with the $66 million made by Humboldt’s timber industry in 2011 (pdf, p.3), the last year for which data was available.

…but the “green rush” is putting a strain on the land

It hasn’t always been a cash crop. The Emerald Triangle’s cannabis growing dates back to the 1970s, when a wave of liberal activists settled there, dropping out of society to go “back to the land.” They found the terrain unusually ideal for growing cannabis. But they grew it alongside other garden produce, seldom in any large scale—and rarely destructively (these hippies were some of the framers of the modern US conservation movement, after all).

California’s legalization of medical marijuana in 1996, as well as steadily rising prices, encouraged their offspring, some less ecologically conscientious than their parents, to enter the business. But it’s in the last few years that things have changed dramatically. From 2009 to 2012 the amount of land cultivated for pot in the Emerald Triangle nearly doubled, to 221 acres, according to the CDFW. An aerial view shows once-dense forests now pocked with “grows,” as pot farms are called. And they’re getting bigger and bigger, says Bauer, with industrial grows now raising 2,000-5,000 plants. Here’s a look at national forest land on Post Mountain, a rural area of Trinity county, in 2005:

Here’s Post Mountain—which locals now call “Pot Mountain“—in 2012:

Many within the industry point to the expanding presence of outsiders: Everyone from Kentuckians to Bulgarians is flocking to the area. Some of this trend, which locals liken to the California Gold Rush of the mid-1800s, is due to a worry that the recent legalization of weed for recreational use in Washington and Colorado might drive down prices.

“People come to Humboldt to grow as much as they can to get that one last hit before it goes legal,” says Tony Silvaggio, an environmental sociologist at the Center for Study of Cannabis and Social Policy (CASP). ”Every year it goes bigger and bigger.”

But another reason is simply that weed is incredibly profitable to grow. Its illegal status, says Silvaggo, inflates its price, and cannabis growers don’t have to pay taxes, rights to water and land use fees the way “legal” industries do.

The water cost is a biggie. A single plant of marijuana needs about six gallons (22.7 liters) of water per day to grow. That means industrial grows need between 12,000 and 30,000 gallons of water per day.

This has exacerbated the water crisis…

The dry summer months happen to be the peak of the April-October pot-growing season. Conscientious growers—typically, long-term residents—invest in tanks to gather and store water during the winter, when it rains more. Unethical growers irrigate by damming streams and using diesel pumps to suck water to their sites. They also tend to pump runoff fouled with dangerous fertilizers and pesticides back into the water supply.

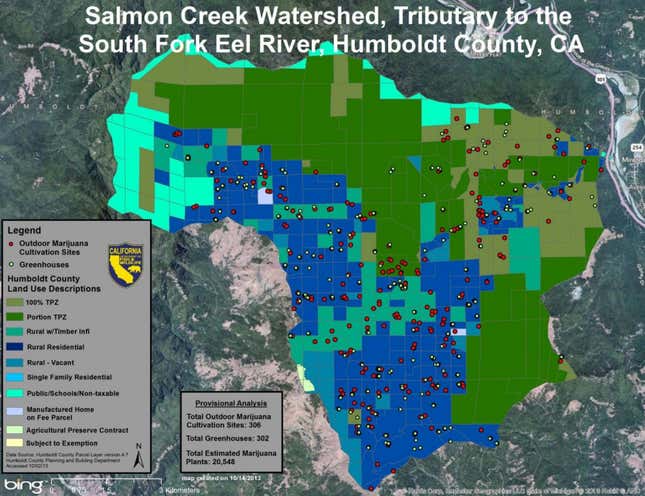

Marijuana growing in four sub-areas of the Emerald Triangle’s watersheds is now consuming 20%-30% of the water in local streams, says the CDFW. That’s scuttling hopes for the recovery of northern California’s beleaguered Chinook salmon population, which the logging industry almost wiped out in the 1950s. Since 2008, water overuse has driven the number of salmon returning to the rivers to spawn to record lows.

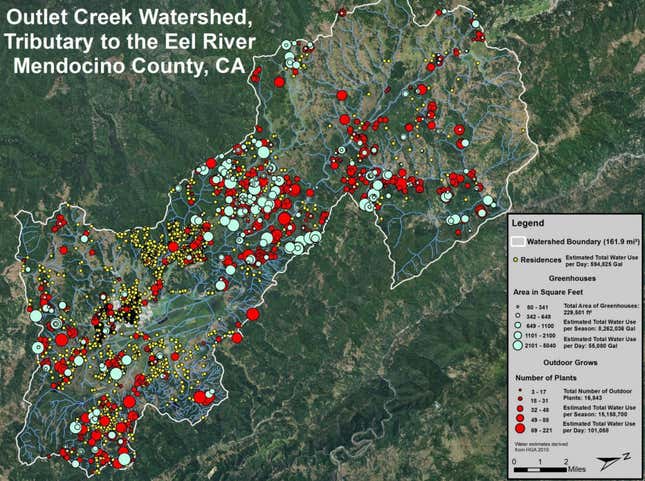

To get a better sense of context, consider the case of the Outlet Creek basin, one of the headwaters of the Eel River and a habitat for Chinook and coho salmon. Outdoor cannabis cultivation in Mendocino’s Outlet Creek watershed consumes an Olympic-sized pool worth of water each week, on average. And that’s just for 160-square-mile (414 square kilometers) swatch of the total Eel River watershed, which spans nearly 4,000 square miles. That concentration of activity is happening all over the 8,800 square miles of Emerald Triangle watersheds. Here’s an analysis Silvaggio and Mother Jones did using Google Earth in early 2013:

… and the US government “is directly to blame”

Cannabis cultivation need not be so bad for the environment. Other local industries, like wineries and timber, have the potential to be worse. While state and local agencies have dozens of workers in northern California focused strictly on protecting the environment from vintners and loggers, no one’s doing that for cannabis growers.

But don’t point fingers at local regulators, says CA Norml’s Gieringer. The “US government is directly to blame for [ending] established efforts to regulate outdoor growth,” he says.

That’s seems like a pretty extreme statement—at least until you hear about what happened in Mendocino.

The Feds cut short Mendocino’s experiment with cannabis regulation…

The story starts in 2010, when Tom Allman, Mendocino’s sheriff, began charging medically licensed marijuana growing collectives $1,050 for cultivation permits, monthly inspection fees of around $500, and $25 for a serial-numbered zip-tie that growers were to attach to each plant (pdf, p.5), certifying that the produce met environmental and public safety standards. The regulation also capped the number of plants per individual at 25, and per collective at 99.

In an interview with PBS in 2011, Allman explained that his motivation was remove the gray area around cultivation in order to honor what California voters had mandated when they legalized medical marijuana, and to free up his officers to focus on crime. “We’re taking money from people who want to follow the law, … and we are using that exact money to go after the people who are breaking the law,” said Allman. “[I]f we can remove the gray, if we can remove the inconsistencies, if we can have people not confused about the marijuana laws, then I have succeeded.”

He didn’t succeed immediately. Growers were initially suspicious that the police would rat them out to the Feds; in the first year, only 18 people signed up. But by the end of 2011, the program had enlisted nearly 100 growers, bringing in $663,000 in fees in 2011—and important source of revenue for an office that normally relied on federal funds.

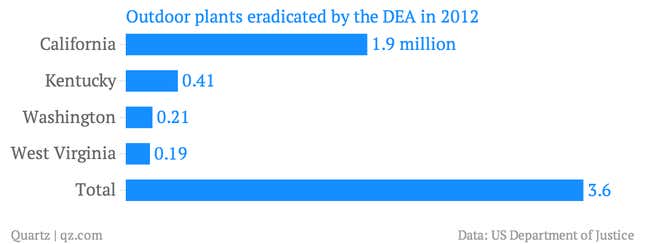

Those fees helped finance Allman’s aggressive campaign against illegal “trespass grows“—meaning those on public land—including some that were illegally damming streams and piping water for irrigation. Allman and his officers eradicated 642,000 illegal marijuana plants in Mendocino county 2011—more than one-third of what the federal Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) typically eradicates each year in all of California. (For comparison, California is about 44 times bigger and 440 times more populous than Mendocino county.)

It helped consumers too, since they could purchase marijuana guaranteed not to contain scary pesticides. And licensed growers were able to ”reintegrate into the county and not feel like outlaws,” as county supervisor John McCowen put it.

But though Mendocino created clear categories of legal and illegal growers, the federal government didn’t see it that way. DEA agents raided farms of Mendocino’s most prominently law-abiding growers—a crackdown on “significant drug traffickers,”said US attorney Melinda Haag. Then 2012, federal prosecutors subpoenaed Mendocino’s records of all participants in the program, which the county’s lawyer said was a breach of medical privacy guarantees. This was a huge blow to the trust forged between growers and Mendocino police. The federal government insisted that Mendocino shut down the program, threatening to prosecute officials individually if they granted permits. In March 2012, Mendocino finally gave in.

“That,” explains CANorml’s Gieringer, ”put an end to the attempt to regulate outdoor cultivation in California.”

… and there’s a cynical theory about why

The federal government isn’t allowed to participate in anything that treats marijuana as legal. But nothing about Mendocino’s zip-tie program required federal involvement—so why did the Feds crack down?

Rusty Payne, a spokesman for the DEA, said he wasn’t familiar with Mendocino’s zip-tie program. However, he says that the DEA is almost exclusively focused on major operations. “You’ll rarely if ever see the DEA show up and bang on someone’s door if they have five plants,” Payne tells Quartz.

While Gieringer, Silvaggio and others who support legalization argue that Mendocino was a successful effort at bringing order to the market through legalization, Payne argues that such systems would paradoxically increase the market share of illegal growers.

“There are a lot of… myths that [marijuana is] safe, that’s it’s okay if it’s regulated. We think it’s dangerous, and one reason is that it’s proven to be a significant source of revenue for the most violent organizations in the world, [such as] the Mexican drug cartels,” he says. “Any time you have a regulated system, you’re going to have taxes and fees. We would see drug trafficking organizations undercut the so-called legal market to the extent that cartels were even more emboldened by dropping their prices because they’d be able to sell even more.”

If Payne’s theory is right, legalization would give the DEA even more illegal activity to crack down on. But what if it turned out, instead, that an expanding legal market enticed some growers out of the black market, thus driving down prices and pushing smaller illegal growers out of business—and at the same time, generating revenue for local police to go after trespass growers more aggressively, the way Sheriff Allman did?

To test those theories you’d need an experiment, and the run of Mendocino’s experiment was probably too short to tell either way. However, a cynical interpretation of the DEA’s attitude is that it fears widespread adoption of programs similar to Mendocino’s would harm the interests of federal agencies, like the DEA, that depend on the “War on Drugs” for funding.

Here’s the reasoning.

Around 60% of the $24.5 billion (pdf, p.19) the US federal government allocated in fiscal year 2013 for drug-control programs went toward disrupting the supply of illegal drugs. Two factors on which Congress evaluates the success of the DEA and its partner law-enforcement agencies are the number of plants eradicated (pdf, p.64-5)—or ”plant count,” as it’s known—and the number of organizations whose operations they disrupt, says Payne. Some 53% of the outdoor plants (pdf) the DEA eradicated in 2012 were in California. That isn’t particularly surprising, given that California grows between a quarter and two-thirds of the rest of the country’s pot, according to sources close to the industry.

Now, what if the whole of California adopted Mendocino’s zip-tie program, creating clear classes of law-abiding and illegal growers? The program would take smaller illegal growers out of business or turn them legal, which would likely bring down California prices. But because the export market would still pay a premium, the biggest trespass grows—which are mainly producing for export out of California—would stay in business, and as Payne says, those are what the DEA focuses on. The surviving operations would be the bigger and better-organized ones that are more dangerous, expensive, and time-consuming to raid. That would make it harder for federal agencies to eradicate the same number of plants and disrupt the same number of operations as they had in the past.

And eventually, legalization in California’s current export markets—meaning, other states—will cause local production capacity to expand and reduce the risk premium. Falling prices will close more and more of these Emerald Triangle trespass grows. When that happens, it will be harder for illegal growers to stay in business by undercutting legal ones in a market where consumers and retailers have gotten used to regulated, quality-controlled legal weed.

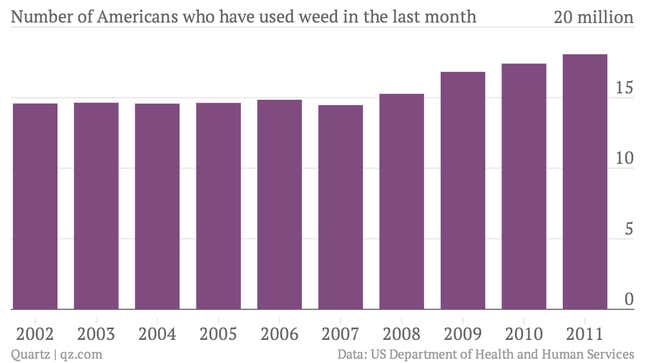

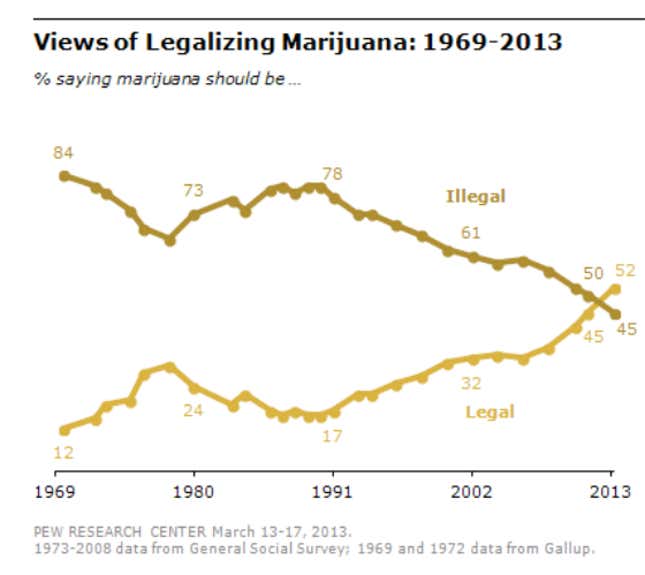

The Office of National Drug-Control Policy (ONDCP)—the White House office that coordinates federal anti-drug efforts, including the DEA—has a dual mandate, to reduce both the supply and demand of drugs. It’s being undermined on the demand side, as support for legalization is rising fast—especially for medical use, now legal in 15 states and the District of Columbia—and so are rates of marijuana use by teens. The mandate to eliminate supply is therefore crucial to being able to justify the ONDCP’s increasingly endangered budget, which shrank nearly 20% (pdf, p.232) in the latest fiscal year. As for the DEA, the Department of Justice, which oversees it, explicitly identifies legalization as a “performance challenge” (pdf, p. 21-2).

What this all boils down to, according to the cynical interpretation, is that successful local-level regulation in California would threaten to deprive federal anti-drug agencies of a large source of their income, and set an example for other states. That could further undermine federal policy, and the agencies’ budgets.

The War on Drugs is now supposedly about the environment…

If this reasoning seems too much like a conspiracy theory, consider that the federal government has long cited the threat to public safety posed by violent “Mexican cartels” (pdf, p.72) to justify its aggressive tactics and hefty budgets. Only last year did Tommy Lanier, director of the ONDCP’s National Marijuana Initiative, quietly admit, ”Based on our intelligence, which includes thousands of cellphone numbers and wiretaps, we haven’t been able to connect anyone to a major cartel.”

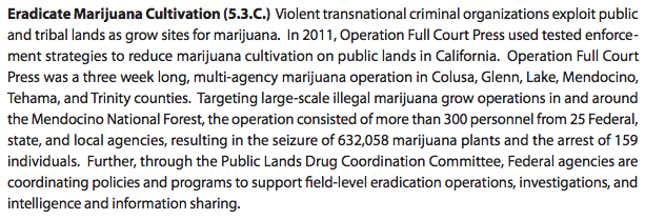

In the 2012 National Drug Control Strategy, which is published by ONDCP, the sole rationale given for eradicating marijuana cultivation in the US was to stop “violent transnational criminal organizations” (pdf, p.28).

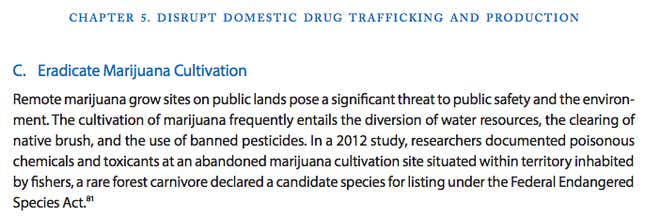

In the 2013 strategy, that changed (pdf, p.45) to an emphasis on the environment:

This, argue some, is of a piece with new federal government talking points emphasizing that cannabis crackdowns are needed to protect the environment. Dominic Corva, head of CASP, says this newfound passion for conservation is more about justifying the anti-marijuana policy in the face of growing public acceptance of marijuana. “Before it was ‘cannabis is bad,'” says Corva. “Now it’s ‘environmental degradation caused by cannabis is bad.'”

The DEA’s Payne says that his organization has long paid attention to environmental destruction by trespass growers. “The environmental impacts—those are obviously concerns for anyone [in regard to] what these drug trafficking organizations are doing to our public lands,” he says. But, he also says, “we’re not environmental experts—we go after drug traffickers.”

…but it isn’t exactly being fought that way

If the end result is that the DEA reduces the cannabis industry’s environmental abuse, does it matter if the way it goes about it is by treating the industry as something to be wiped out?

In all fairness to the DEA, it isn’t supposed to be regulating water pumps. Indeed, saddling an anti-drug agency with environmental policing seems a perverse way of doing things, especially when other federal agencies are refusing to do it. Take, for instance, the National Forest Service. Once focused on regulating (and promoting) economic development on forested land, the agency has shifted more recently toward protecting the environment (pdf, p.3), including watersheds. Part of its job is to research how commercial industries like logging affect the environment in forests. However, it has steadfastly rejected EPIC’s requests that it do the same for marijuana cultivation. “The best way to minimize impacts to affected resources is by discouraging this criminal activity through aggressive law enforcement,” says the US Forest Service (pdf).

Even if the DEA had the capacity to target the most egregious environmental abusers, it wouldn’t be sufficient, says EPIC’s Hughes. “These are really profound environmental harms that need more than just a bust to be dealt with,” he says. He argues that public land management should be prioritized over law enforcement.

CASP’s Silvaggio says that the DEA’s focus continues to be on destroying plants and arresting easy targets—low-level workers. That means it’s disrupting industrial grows basically by creating minor staffing headaches. And, if the growers subsequently replant, they end up using even more water.

On top of that, law-enforcement officers don’t generally know a lot about managing the environment, and lack the staff who does. That means they sometimes lean heavily on local volunteers to clean up pot-growing sites after a raid, says EPIC’s Hughes. Because that risks putting volunteers in harm’s way—one died on the job in Sep. 2013—law enforcement operations tend to stay away from the bigger, riskier grow sites in remote, hard-to-access areas, he adds, meaning those grows continue to do environmental damage.

Busting trespass grows, the main focus of the DEA’s work, also does nothing to limit damage to the water supply from growers on private residential land. Compared with public-land grows, those account for a majority of cannabis cultivation in the area, says CDFW (pdf, p.25) and others close to the industry.

So what’s the future of the Emerald Triangle “green rush”?

There’s a glimmer of hope for northern California’s streams yet. The federal government recently showed signs of relaxing its “enforcement-only” position: It said it plans to scale back the practice of using legal marijuana businesses’ bank records to prosecute them. (That practice has forced many growers to use cash only, which encourages crime.)

And California’s new state budget proposal earmarks $3.3 million (pdf, p.108-119) to “improve the prevention” of destructive water use by marijuana cultivators and to protect endangered species. It’s not clear whether the budget, if approved, will be earmarked for enforcement only—meaning, to help state water and wildlife departments join the federal campaign against trespass grows that are polluting or overusing water, for example—or for education, community outreach and other types of programs, which might violate federal law.

Bauer of the CDFW, thinks the budget will finally give him the staff needed to educate growers on winter water storage and other best practices. Busts, he says, won’t be the priority. On the other hand, EPIC’s Hughes is skeptical that the new budget would fund anything besides the usual—enforcement. “The state and the counties I believe are still running scared… because of the threat that the Feds will come down and say that [they] are involved with an illegal activity.” In other words, he argues, northern California and its water supply “will continue to pay the environmental fallout of the Drug War.”