Illicit capital flows into and out of the Philippines are sapping billions from the real economy, perpetuating corruption, depriving the government of tax revenue, and hurting growth, according to a report by Global Financial Integrity (GFI), a non-profit group.

Most of this money-laundering is facilitated through what’s known as fake trade invoicing, which allows exporters and importers to avoid paying taxes on traded goods. Exporters declare only a fraction of their actual sales to the Philippines customs authority, and hold the payment for the remainder in an offshore bank account to dodge taxes. Importers, meanwhile, underreport the amount they’re bringing into the country, smuggling the rest in effectively duty-free. Understated imports—or, in more everyday language, smuggling—account for most of the fake invoicing, or $2.97 billion; undeclared exports added another $880 million.

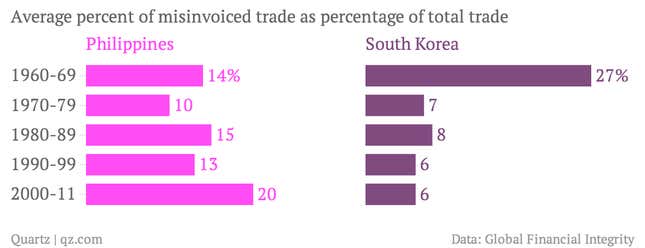

“This problem is so ubiquitous in the Philippines that, over the past decade, 25% of all goods imported into the Philippines—or one out of every four dollars—goes unreported to customs officials,” said Brian LeBlanc, a GFI economist, in a press release. “[W]idespread under-invoicing has a severely damaging effect on government revenues.”

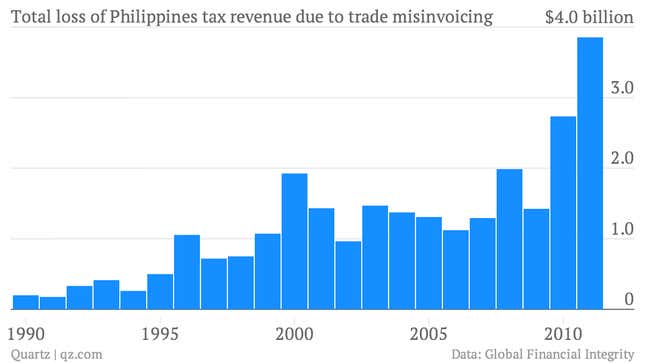

How damaging? Since 2000, illicit capital flows have drained an average of $1.5 billion in tax revenue each year, and that number is growing. “The $3.9 billion in lost tax revenue in 2011 was more than twice the size of the fiscal deficit and equal to 95% of the total government expenditures on social benefits that year,” said LeBlanc. It also, points out GFI, fuels crime and the gray economy.

One reason there’s so much fake invoicing in the Philippines is high import tariffs, which give traders an incentive to dodge them, says GFI, noting that importers tend to smuggle goods with higher duties. The trouble is, those revenues are particularly important to the government; tariffs generate 22% of its total taxes, compared with an average of 0.3% for OECD countries, said GFI. And it desperately needs that money especially in the wake of disasters like Typhoon Haiyan, which devastated the archipelago last year.

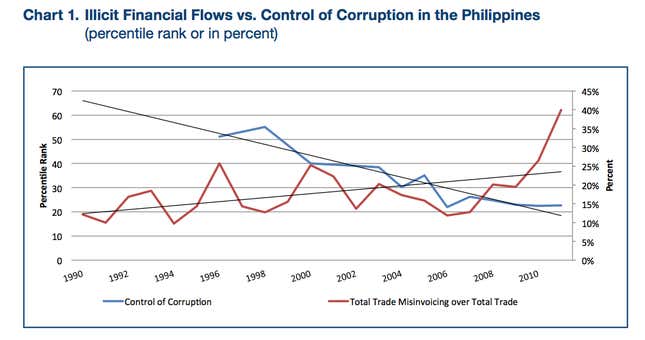

Inaccurate trade invoicing also shifts funds into the black market for domestic and foreign currencies. Those in turn fund more underground economic activity, which is also untaxed and unregulated. This not only comes at the expense of the official economy but also perpetuates the cycle of corruption. As you can see in the chart below, illicit trade invoicing is closely linked with corruption:

The report notes that in South Korea, a country with a similar export-oriented economic model, mis-invoiced trade has declined as corporate governance has strengthened. In the Philippines, it’s been getting worse.

In 2010 Benigno Aquino won a presidential election in the Philippines as an anti-corruption crusader. But GFI’s data go back only to 2011, so it’s hard to know how well Aquino is doing. For one thing, the economy grew 7.2% in 2013, behind only China among Asian economies. As GFI’s research highlights, higher GDP growth tends to boost confidence in the economy, which should discourage capital flight through misinvoiced exports. But the bigger question for the Philippines is how its poorer households are doing. If illegal inflows mean the government can’t give them as much aid, the real economy will continue to suffer.