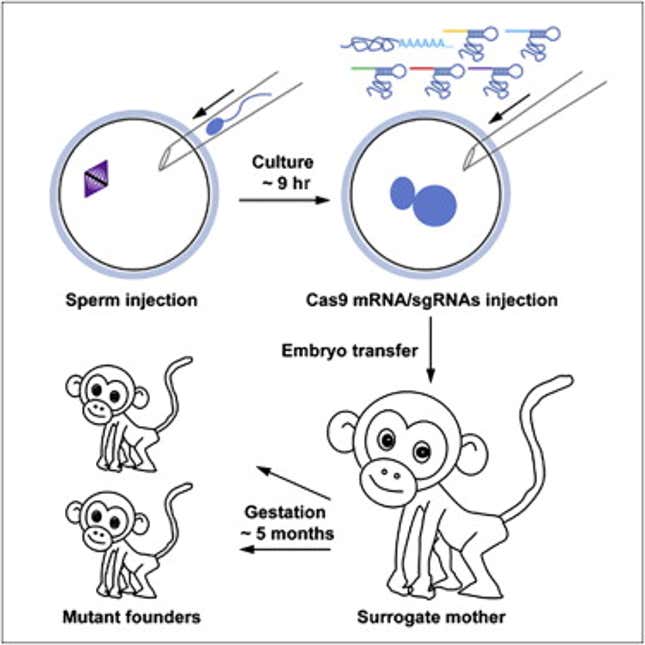

Something major just happened in China: Government-backed researchers turned two macaque monkey embryos into adorable newborn mutants.

It’s the first time anyone’s pulled off this kind of gene-editing in primates using Crispr, a technology that has been used on mice, rats and zebrafish. And it means scientists can use Crispr to program monkeys with the gene sequences of human illnesses. Since macaque monkeys have a lot more genetically in common with humans than mice—the current “guinea pig” for those procedures—scientists stand to learn a lot about how to treat those diseases.

That’s a big deal. But the really huge implication isn’t about watching sickened monkeys. It’s about what this means for genome-editing in humans.

DNA malfunctions cause many diseases. Fix those errors, and you fix the diseases. The ability to edit the genes of primates puts us a lot closer to doing that. To understand how this might work, think about hemophilia. Made famous by the the Russian royal family the Romanovs, this condition occurs when an inherited, single-gene mutation leaves a person—almost always a male—without the ability to produce a blood-clotting protein, which causes life-threatening “bleeding episodes” throughout their lives.

Crispr could—in theory—be used to fix the mutation, turning would-be hemophiliac embryos into healthy baby boys, who then pass on those healthy genes to their offspring. The same process could edit the DNA sequences responsible for Huntington disease, the extra chromosome that causes Down syndrome or, down the road, maybe even the genes that lead to autism or depression.

But what about traits deemed desirable? That’s trickier. Genetic factors that influence things like intelligence or even something as seemingly straightforward as height are really complicated. But a Chinese company is already working on identifying the “smart” genes in humans. If it succeeds, editing those sequences isn’t a big leap.

And what’s to say the genes have to be human? Scientists already use mouse DNA to make a pigs digest phosphorous better, and jellyfish DNA to make Day-Glo fish. Similar tweaking of monkey genes will tell scientists a lot about the opportunities to do the same in people.

These are unnerving possibilities for doctors. Many aren’t even comfortable (paywall) with screening embryos for diseases, let alone tinkering with their DNA. Big concerns include whether it’s ethically okay to screen for genes that simply might cause a disease, or that cause disorders only in adulthood. And then there’s what this implies about people with Down syndrome or, say, intersex people—that they can be “fixed.”

But not everyone is as squeamish—including the team of monkey-mutating scientists, who hail from Nanjing Medical University and Yunnan Key Laboratory of Primate Biomedical Research. “We believe the success of this strategy in nonhuman primates gives lots of potential for its application in humans,” one of the lead researchers, Weizhi Ji, told MIT Technology Review, “but we think due to the safety issue, it will take a long way for expanding this strategy to human embryos.”