The only thing fleeing faster than Puerto Rico’s population is its financial credibility.

The most recent blow to Puerto Rico’s economic reputation is yet another downgrade of its debt, this time to junk. S&P slashed the rating on Tuesday because, in a nutshell, the commonwealth is going to need a lot more money and that money isn’t going to get any easier to come by. Although some initial reports indicate that investors are shrugging off the downgrade, the possibility of further downgrades by the other two major ratings agencies, Moody’s and Fitch (which both currently rate Puerto Rico a mere notch above junk), could spark a sell-off by institutional debt holders. That would make it even more difficult for the government to raise the cash it sorely needs.

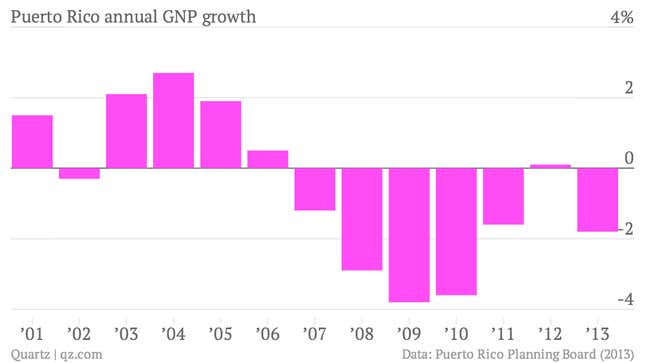

Puerto Rico is in a pretty precarious spot. But it’s hardly something that happened overnight. The island has been crawling its way toward today’s economic mess for quite some time. “If you look at the numbers, the economy has shrunk by something like 15% over the past six or seven years,” economist José J. Villamil told Quartz. Puerto Rico’s economy has been getting smaller for almost eight years, as the chart below shows.

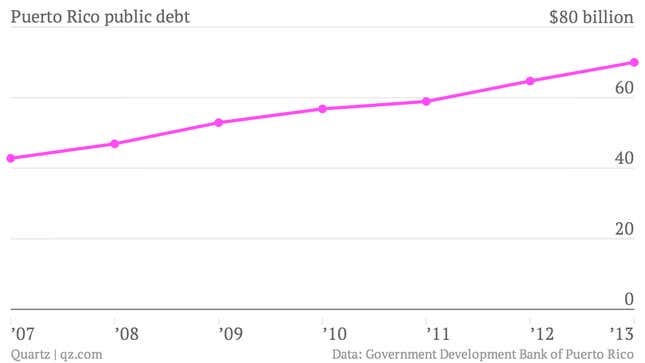

The plan of attack so far has been to issue debt, and lots of it, in the hope that some extra money will help jumpstart its laggard economy. But all that’s done is pile up Puerto Rico’s IOUs. The small island’s outstanding debt now totals some $70 billion (more than that of New York, and nearly four times that of Detroit).

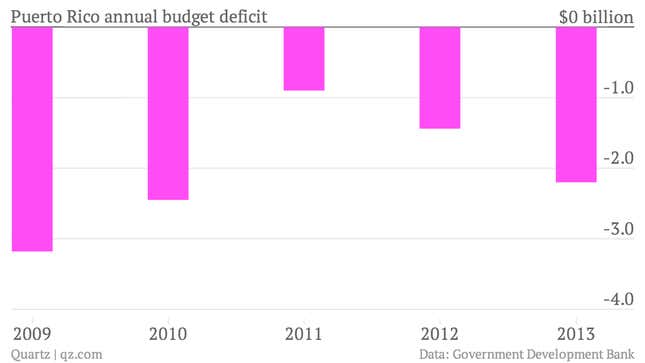

All that borrowing has not been offset with a plan for proper repayment, and the government has shown a dangerous inability to cut spending. Puerto Rico has been running massive budget deficits for years now.

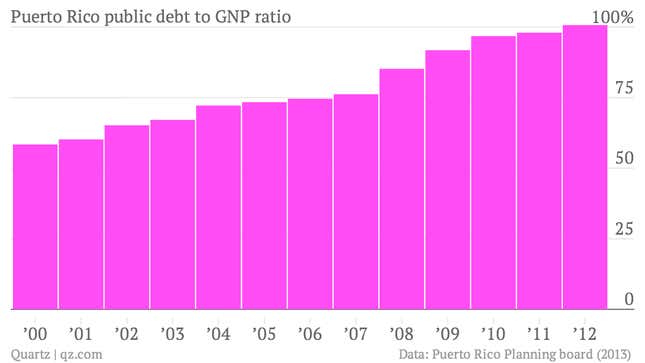

Its debt-to-GNP ratio crept above 100% in 2012, and has continued skyward.

The deeper Puerto Rico sinks into debt and economic stagnation, the more difficult it’s going to be to climb out, Villamil said in a recent report on the island’s economic struggles (pdf, p. 4). “The longer the contraction, the more intractable the situation becomes,” he said. To make matters worse, nearly a third of Puerto Rico’s labor force is employed by the government, meaning much of the borrowed money is tied up in salaries, leaving little for economic development.

Political cycles also bring discordant and counter-productive swings in policy. Couple those with a fast-fleeing population (Puerto Rico is on pace to lose nearly 40% of its population by 2050) and a shrinking pool of workers (labor participation is now roughly 40% on the island, compared with the upwards of 60% in the US as a whole), and you have a recipe for economic disaster.

The possibility of further downgrades is real, but—according to Villamil—unlikely. “Moody’s is the most important, but I don’t expect Moody’s to take that step,” he said. Then again, S&P’s decision caught many, including Villamil, off-guard. “I think S&P jumped the gun,” he said. “Everything they had asked of the island had been obliged.”

Puerto Rico’s governor remains adamant that he will not allow Puerto Rico to default on its debt. “I can assure you that Puerto Rico will not default,” Alejandro Javier Garcia Padilla told the Washington Post late last year. But Padilla alone cannot steer the island clear of default. If the precipitous pattern of overborrowing and underperforming continues, Puerto Rico may eventually have no choice.