America has fallen out of love with orange juice.

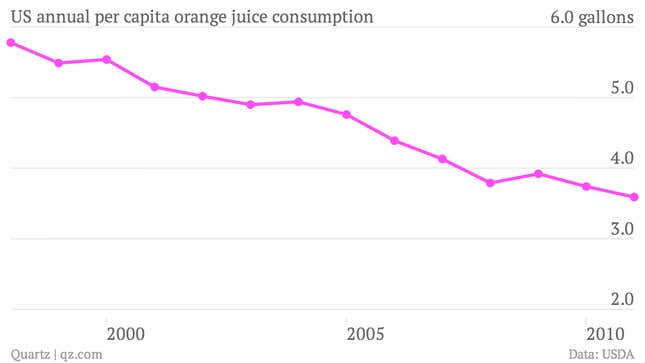

Sales dropped almost every year for the last decade. Last year, orange juice sales hit their lowest level in at least 15 years, according to Nielsen. Over the same period, per-capita consumption fell roughly 40%. And this year is looking to be another rough one for big orange.

Orange juice’s precipitous decline is a big deal. For nearly five decades, the sweet beverage made its way onto more and more American breakfast tables nearly every year. At its height, almost three-quarters of American households bought and kept orange juice in their refrigerator, according to Alissa Hamilton 2009’s book Squeezed: What You Don’t Know About Orange Juice. But shifting American eating habits—which stigmatize sugar and leave little time for breakfast—and surging juice prices have done significant damage to American demand.

Concentrate, Concentrate

America has lived without orange juice before. Until the late 1940s, orange juice wasn’t even a widely available commercial drink. The little orange juice Americans imbibed was either fresh-squeezed, or boiled and then canned—a process which helped preserve the juice, but also made it taste terrible.

After World War II, a group of scientists changed the American orange juice landscape forever. Determined to find a more palatable intersection between preservation and flavor, these scientists developed a new process roughly based on the one they saw used to dehydrate food during the war effort. Instead of boiling the juice, they heated it lightly until water evaporated. Then, they’d add a touch of fresh orange, which gave the concoction a “fresh” taste. Orange juice “from concentrate” was born. As was the industry’s marketing push.

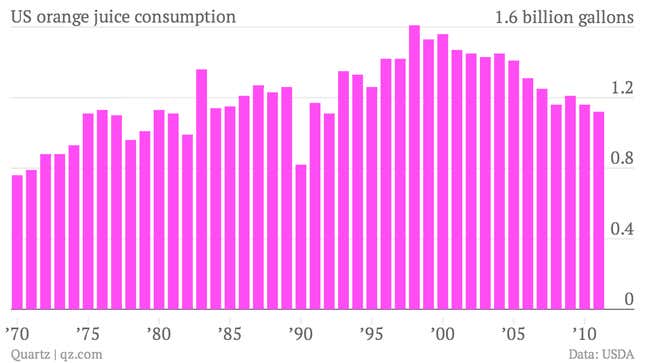

The product was a hit. Per capita orange juice consumption jumped from under eight pounds per person in 1950, to over 20 pounds per person in 1960. Florida’s production of concentrated juice leapt from 226,000 gallons in 1946 to more than 116 million in 1962, according to a report by agricultural economist Robert A. Morris. By 1970, 90% of Florida’s oranges were being used to make orange juice and the vast majority of that was from concentrate.

The increased popularity of flash-pasteurized, ready-to-drink juice advertised as “not-from-concentrate” helped drive consumption still higher in the 1980s and 1990s.

But as you can see, things started to roll over in the late 1990s. Since 1998, US orange production and orange juice sales have fallen virtually every year. That decline comes despite strong population growth in the US, which means the average American consumes far fewer oranges today than she did in 2000.

Why?

Orange juice is getting more expensive

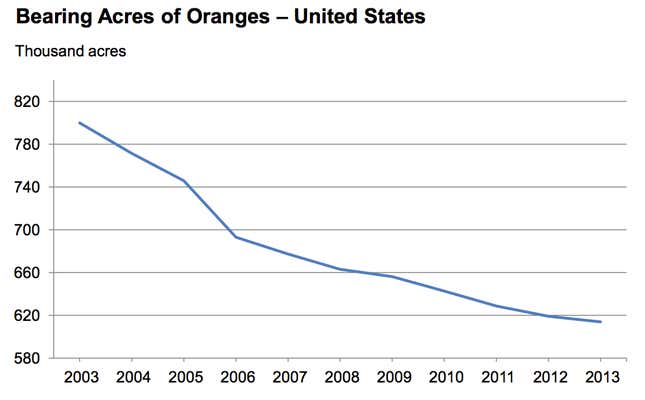

An insect-born disease known as “citrus greening” has been hampering production, reducing supply, and raising prices. The disease hit south Florida in 2005. Scientists now believe just about every orange grove in the state of Florida is infected. Given that Florida still produces the vast majority of the US’s orange juice (over 80%, according to Florida Citrus) that’s a pretty big problem.

“It’s the most devastating issue the industry currently faces and has ever faced,” Matt Salois, chief economist at the Florida Department of Citrus, told Quartz. “We lose more trees in a given year than are actually being planted.” The US orange-tree population has fallen by nearly 25% since 2003, according to the USDA. Trees aren’t merely dying off, they’re becoming far less productive, too. The infection is increasing the rate of fruit drop (the rate at which unripened oranges fall off trees) and decreasing the size of oranges, sometimes by so much that they aren’t even juice-able. This is the sort of sad orange the disease has given birth to.

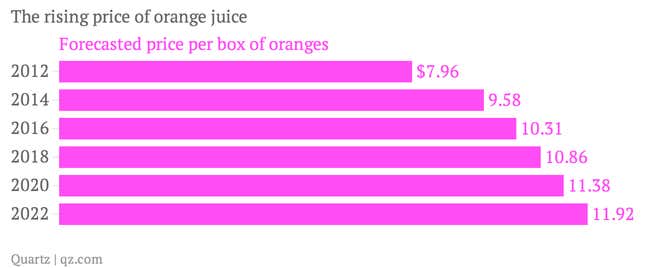

With few trees, less productive trees, the price of growing oranges is rising. The cost of growing orange trees has doubled from roughly $1,500 an acre in 2000 to as much as $3,000 today, according to Florida Citrus estimates. And when something gets more expensive to make, it tends to get more expensive to buy, too. Wholesale orange juice prices today are about twice what they were in 2000.

Orange imports to the US have risen slightly in recent years, but not nearly fast enough to offset the fall in domestic production. Brazil, which produces almost all of the oranges consumed by the rest of the world, has suffered through its own orange problems.

Americans aren’t eating breakfast

Orange juice’s traditional ties to breakfast aren’t doing it any favors either.

That’s because Americans aren’t eating breakfast like they used to. Breakfast has been on the decline for over 20 years now, according to a recent study (paywall). Some 89% of American adults ate breakfast back in 1971, according to data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys. As of 2002, that number has fallen to 82%, and is likely lower now.

“We’ve seen the evolution away from breakfast as a meal, which orange juice has long been associated with,” Salois said. “Younger consumers especially have been increasingly willing to replace OJ at breakfast time, and it’s been big a problem for the industry.”

And they’re trying to eat less sugar

Americans are also getting a lot more finicky about what they put in their bodies. A growing awareness around the harms of sugar, of which orange juice has plenty, is hurting sales.

The industry has responded, in part, by suggesting consumers continue to drink orange juice, but just less of it. It’s also becoming abundantly clear that Americans no longer need to drink stuff to get their vitamin C—thanks to a proliferation of pills, chewable tablets, and powders.

And then there’s the growing worry that the “fresh” juice the industry has been touting for years may not be all that fresh, after all. Pepsi, which owns Tropicana, has come under fire for its use of the term “all-natural.” And Coca-Cola, for its Simply Orange brand of juice, which critics say may not be all that simple.

So where does orange juice go next?

It might become a luxury drink.

After all, as US orange supplies continues to shrink—annual production could dip below 100 million boxes by 2020, the lowest level since 1964—prices will likely continue to rise.

Whether Americans will continue to buy orange juice at higher and higher prices remains to be seen.

Increasingly, consumers seem to be accepting the challenge posed by the 1980s Minute Maid tagline: “For juice that tastes fresher, you’ll have to squeeze it yourself.” The orange industry probably didn’t expect that two decades later, Americans might be happy to try.

“People are increasingly making it at home,” said Salois, the Florida Citrus Department economist. “It’s something we’re aware of.”