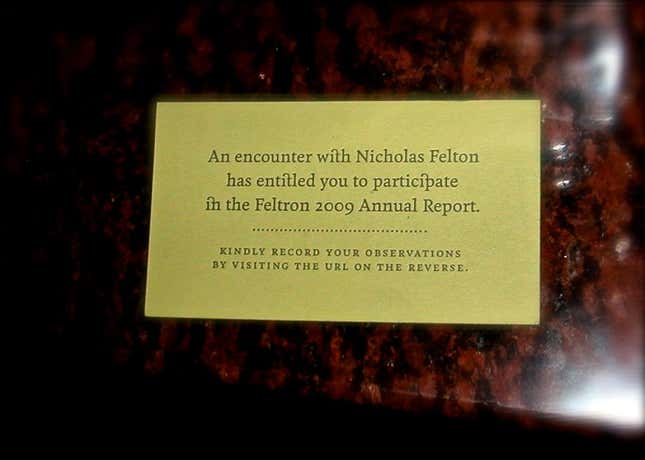

How many gadgets does it take to comprehensively track your life? How about three fitness trackers, a camera on your chest, and three apps running night and day on your smartphone, plus a blood alcohol monitor? That’s what it takes for quantified-self guru Nicholas Felton—the author of nearly a decade of annual reports on the minutia of his own life, from restaurants visited to the time spent on work and play.

Most people who “quantify” their lives—that is, collect data on their activities and behavior in order to tweak their lives for the better—have a limited set of data to work with. Fitness trackers, for example, are all the rage. But Felton, who as a designer at Facebook helped design its Timeline before he left the company last year, has already moved on to a broader range of data collection. Until now, most of what he’s wanted to measure has required manually entering the data about his life (a process he seemingly mastered, given that he’s now developed an app that others can use to do it)—but passive sensors are catching up.

“This is the 10th anniversary of the report,” Felton told Quartz, “and the whole world is self-tracking now. We’ve come so far. I wanted to figure out if the tools exist now to really capture my life in the resolution I’ve gotten manually.”

And since Felton wasn’t going to wait around for one all-encompassing life-tracking wearable computer to come out, he’s using many: A FitBit, a Basis, a Nike FuelBand, and a Narrative Clip. “I wear a Basis because, on top of the usual things like steps and sleep, it also gives me heart rate and skin responses,” Felton explained. The Nike FuelBand’s data collection is technically redundant—it’s basically a pedometer—but he likes the way the data is presented. And the FitBit can track flights of stairs climbed, which is presumably going to be one of the trends that Felton highlights for 2014.

But wearing three fitness bands is no big deal. “It’s winter,” Felton joked, “I’m wearing a lot of layers at the moment.” And in any case, he’s been wearing the three trackers for a year already. “It’s the camera that’s really controversial,” he said. The Narrative Clip, which takes a picture automatically every 30 seconds, tends to worry people. “Usually I’ll open up my phone and show them how boring my life is,” Felton said. “It’s mostly just photos of my computer.”

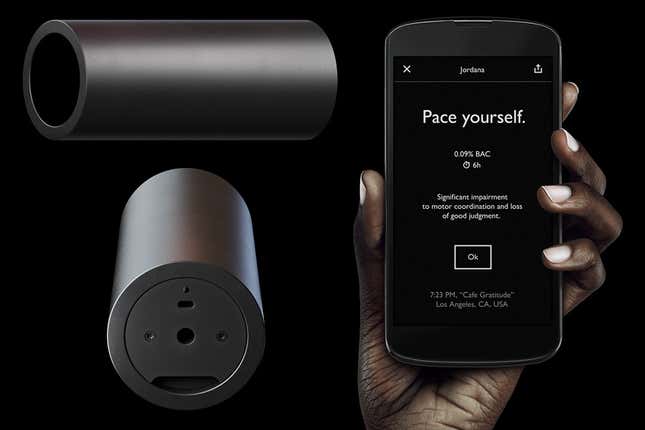

To fill in the gaps left by his wearables, Felton also uses a grab bag of apps and gizmos: RescueTime, which tracks computer activity; Moves, an iPhone app that keeps tabs on movement and location; Automatic, which sends data on your driving habits to your phone; and Lapka, a smartphone-enabled blood alcohol monitor. “For me, Moves has been the most revolutionary,” Felton said. The use of GPS allows the device to do more than just collect how many steps you took—it can tell you, for example, that you walked to a particular restaurant, and then drove back to your house. “I spent so much time manually tracking where I went, and this gives you context for where you’re going.” Felton will save lots of time in general by using his fleet of trackers and apps. “It’s liberating to not be on my phone all the time recording everything,” he said. “A weight has been lifted.”

Still, Felton knows that what seems easy to him would be preposterous for most. “It’s a big challenge to keep them all healthy,” he said of his menagerie of wearable devices. “Syncing them at night, keeping them juiced, making sure they’re always ready to go…That’s why most people can’t support more than one.”

Felton is counting on the rumored Apple iWatch to collect this life data on a single device. “I’m excited about the potential of an Apple smartwatch,” he said, “because as soon as you start tying health monitors to other utilities that people need or want—as soon as you have that secondary use—people will be willing and able to maintain these devices.” Some of the devices Felton is using—particularly the Lapka blood alcohol monitor and the Narrative Clip—won’t ever be mainstream, in his opinion. But he thinks that some level data tracking will be, if only because people’s activities are already being tracked by governments and businesses, and the data isn’t freely available.

“If you want it,” Felton said, “you should have it. Take your location data and use it to live your life better.”