“My wife and I like to lay in bed and watch Netflix,” Tom Wheeler, chairman of the US Federal Communications Commission, said the other day. But when their internet connection slows down, breaking up the video feed, Wheeler’s wife is incredulous: “You’re chairman of the FCC,” she says to him. “Why is this happening?”

Why, indeed.

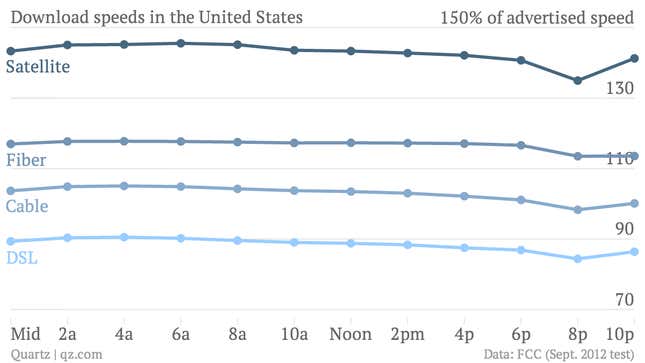

The buffering in Wheeler’s bedroom is familiar to any American who has tried to stream video over the internet at night, when their neighbors are doing the same thing. Look at the dip in average download speed between 8pm in the chart below (where each datapoint spans the following two hours):

During that primetime, about a third (pdf) of all internet traffic heading into North American homes is carrying data-heavy movies and TV shows from Netflix. Transmitting all those bits will become an increasingly severe challenge as more people opt for streaming video over traditional television. Even though TV and the internet often travel over the same pipes, the infrastructure to make each work is vastly different. And the internet is way behind.

Consider what will happen tomorrow, Feb. 14, when Netflix releases all 13 episodes of the second season of House of Cards, its acclaimed political drama. Owing to positive reviews of the first season and aggressive marketing by Netflix, demand for the show is likely to be strong. Throw in some terrible weather, and it’s easy to imagine a huge portion of the 33.4 million households that subscribe to Netflix’s streaming service in the United States trying to watch House of Cards at the same time on Friday night (notwithstanding that it’s Valentine’s Day).

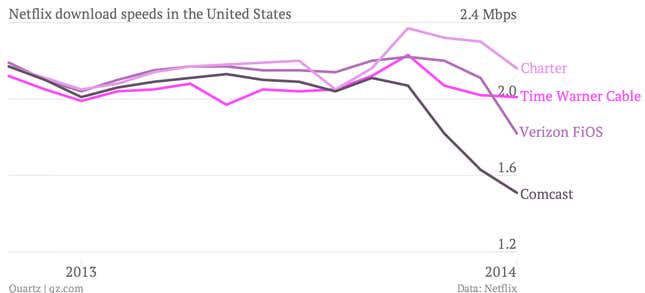

That is going to be a problem because primetime download speeds over some of the country’s biggest internet service providers (ISPs) have been falling in recent months, according to Netflix:

The drop has led to accusations that Verizon and Comcast are throttling, or slowing down, Netflix over their networks. If true, it would dovetail with a recent court decision that overturned the US government’s “net neutrality” regulations, which required ISPs to deal with Netflix traffic the same way as Google’s YouTube or some random web page.

But the ISPs deny it. “We treat all traffic equally, and that has not changed,” Verizon said.

Netflix also says it isn’t being throttled. The company would like to see those speeds improve—its monthly publication of the data is a shaming exercise—but figures the ISPs wouldn’t dare to intentionally degrade their customers’ experience. Public opinion clearly favors Netflix over cable TV and internet providers.

So what is slowing down Netflix?

“While investors and politicians spend significant time and energy focused on net neutrality,” BTIG analyst Rich Greenfield wrote in a note this week (registration required), “we believe peering and interconnection are the issues actually impacting content creators, distributors, CDNs, and consumers today.”

We’ll explain what that means.

Even if millions of people want to watch House of Cards on Friday, Netflix doesn’t have to send each of them a unique copy of the show. The company uses content delivery networks (CDNs), including one of its own, to send the data just once. ISPs, which get the data into homes, can choose to peer with these CDNs, essentially creating a direct connection that bypasses the rest of the internet and keeps things working speedily for Netflix and its customers.

Peering is different from traditional internet transit. And while maybe it should be, peering has never been subject to net neutrality rules. It’s more like a private internet to help Netflix and other companies—Google, Facebook, Amazon, and Microsoft all rely heavily on peering arrangements—get their data to people faster.

How those peering arrangements work can vary. Sometimes the CDN pays the ISP. Sometimes no money changes hands because a roughly equal amount of traffic travels back-and-forth between the two. And sometimes it’s a mess, as when Comcast (an ISP) suddenly demanded that Level 3 (a CDN) pay for the increasingly heavy bandwidth it was sending to Comcast on Netflix’s behalf; that dispute was settled last year.

Peering into internet TV’s future

“Peering was an engineering concept in the early days of the net,” explained the FCC’s Wheeler at an event last month. “The engineers, as engineers are wont to do, built something that was straightforward and usable and would operate. And the economics of it were not even close to their thinking.”

There’s your likely answer to what has been slowing down Netflix—and will be crucial to the future of internet TV: the economics of peering.

Should Netflix and any CDN it uses have to pay for better access to American homes? Peering, as the name would imply, was conceived as an equal partnership, but the ISPs no longer see it that way. They would like to get paid. Some already do.

Netflix, for its part, would like to side-step the issue with its own version of a CDN called Open Connect. Cablevision is the most significant American firm to sign up for OpenConnect, which provides direct access to Netflix’s servers with no money exchanged. Larger rivals, including Comcast and Verizon, have refused.

So if anything is behind the recent slowdown in Netflix speeds, it’s likely a peering dispute. (Verizon hinted as much in its recent statement.) Sometimes these disputes break out into the open—as with Comcast and Level 3 in 2010 or Verizon and Cogent in 2013—but mostly, they remain behind closed doors.

If House of Cards starts to buffer for viewers tomorrow, that’s why.