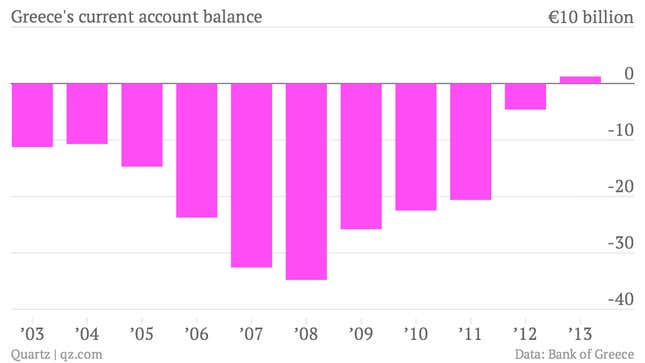

Since the modern Greek state started keeping track, it has never recorded an annual current account surplus. The current account is the broadest measure of what a country buys from abroad and sells to foreigners, covering goods, services, and investment flows.

Last year, Greece eked out a current account surplus of €1.2 billion ($1.7 billion), or just under 1% of its GDP, according to data released today. This was the first annual surplus since official data began in 1948. During the peak of Greece’s financial crisis, its current account deficit grew to around 18% of GDP; a heavy reliance on imports and borrowing from abroad put Greece in a precarious place when the bottom fell out of the European economy. (This is not unlike the turmoil currently seen in similarly imbalanced emerging markets.)

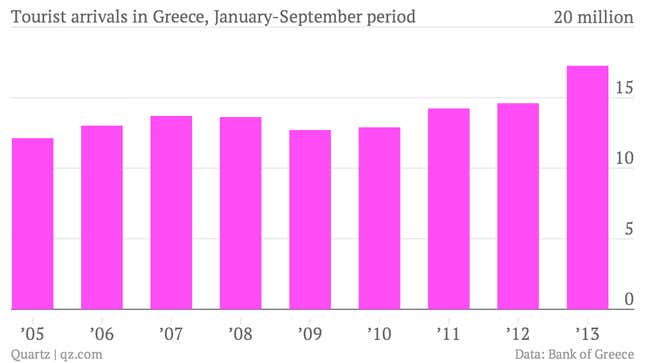

According to a recent assessment of its economy, the creditors overseeing Greece’s €240 billion international bailout were under the impression that it would run a current account deficit through at least 2016 (pdf, p. 16). The faster reversal is thanks to a number of factors, including a modest pickup in exports, weak imports, and the lower interest bill for bonds the government restructured in 2012. Another important factor, the Greek central bank says, is a big influx of tourists, with both arrivals and spending by visitors up by around 15% in 2013.

Greece’s depressed economy didn’t detract from its surplus of sun and sand; vacationers are increasingly drawn to the Mediterranean outpost as falling prices make it more affordable (especially now that bouts of popular unrest have subsided.)

That said, deflation doesn’t help lessen Greece’s debt burden, while austerity isn’t doing much to help the country’s sickly labor market. Chatter about replenishing or restructuring Greece’s bailout program reflects the fear that the economy isn’t yet on a sustainable footing (pdf). But for a country where the numbers have been unrelentingly negative for so many years, any positive news is noteworthy.