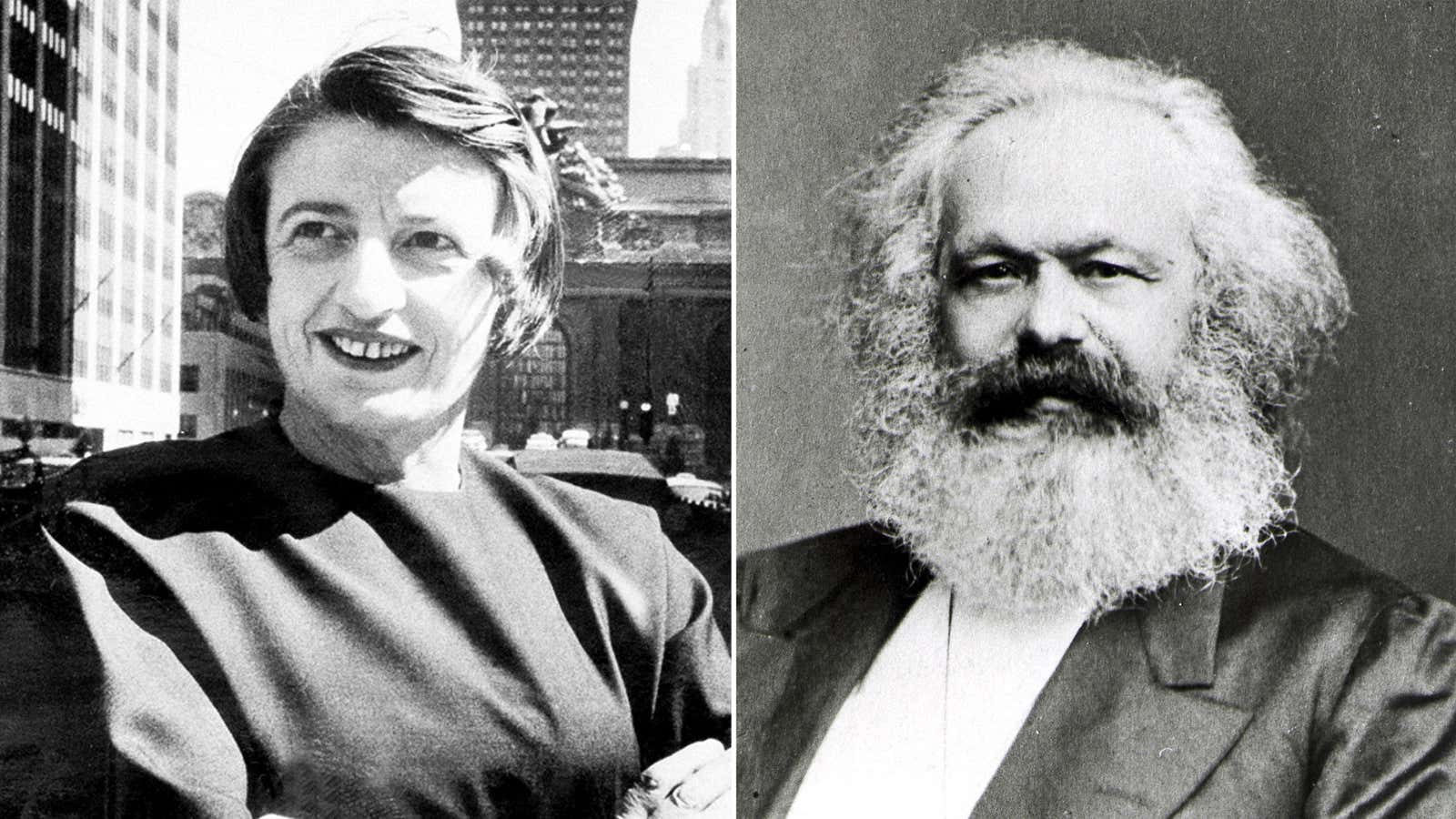

A report in The Economist on Ayn Rand’s growing popularity notes that the heroine of American libertarians has some big fan bases outside the US—most of all in Britain, Canada, Sweden, and India, where “Rand’s books outsell Karl Marx’s 16-fold.”

Rand’s minor cult status in India has been noted before. According to one report, Indians searched Google for Ayn Rand more often than anyone else until 2007, when a Tea-Party obsessed America took over the top spot. It’s typically read as a reaction to the country’s stratified social hierarchy and heavy, lumbering government, anathema to the fiercely self-sufficient heroes of Rand’s novels. Indeed, one Indian libertarian, writing a few years ago—before the rise of the Tea Party—argued that she was even more respected in India than America because Indians actually live in the “collectivist, pseudo-statist, tradition-bound, mystic society” that she would have decried (unlike American Rand fans, who only think they do.)

David Seaton, a left-wing American blogger and journalist living in Spain, sees a darker explanation. Rand, he conjectures, is probably a favorite with upper-caste, rich Indians, who take one of her key precepts, the rejection of altruism, as a license to ignore India’s searing poverty and institutionalized racism. In that sense, he argues, Indian Randians are a mirror-image of those in America, who prefer to close their eyes to their country’s growing wealth gap, its persistent racial discrimination, and the vanishing of its vaunted meritocracy.

That might have some truth to it. But it skates over the oft-remarked contradiction in American libertarianism: that many of Rand’s biggest American fans are not rich elitists fighting off the collectivist clamor of the great unwashed, but blue-collar Tea-Partiers who have themselves felt the financial crisis at its sharp end. And that’s tied to another difference between Indian and American followers of Rand: A lot (though by no means all) of the Americans who claim to her devotees are religious and socially conservative, though Rand herself was a staunch atheist; the Indian ones are more likely to come from the professional class and to reject religion and tradition.

So it seems fair to say that Indians are purer in their Randophilia than Americans are—or at least, understand Rand’s philosophy better. But the dissonance between the two groups also shows that a predilection for Rand isn’t necessarily about embracing her dogma. As a preacher of individualism, she can be a remarkably flexible standard-bearer for anyone who feels like rejecting the established order, whatever that order may be.

It’s ironic that Marx has fallen so far in India, because he was, in a sense, the Rand of his own day: a radical calling for the upheaval of the social order. More to the point, as India prepared to shake off colonial rule, he had enormous influence on the economic thought of its leaders. But every generation needs its own radicalism.

Rand’s popularity in other countries ought, then, to tell us something about them. It’s notable that she seems not to be nearly as much of an icon in Russia, which gave birth not only to her but also to the socialist dictatorship that inspired her philosophy. Her Russian Wikipedia page, to use an unscientific but nonetheless telling measure of interest, is considerably shorter than the versions not only in English, French, and Spanish, but also Swedish, Hebrew, Latin (!), and Tamil. That could be because by the Russians are by now living in something approaching the red-in-tooth-and-claw ideal of a Randian society, and have decidedly mixed feelings about it.

Meanwhile, her standing in Sweden—which apparently leads in non-English Google searches for Rand—could stem from a backlash against the welfare state that she called “the most evil national psychology ever described.” If she is indeed as popular in Israel as her Hebrew Wikipedia page suggests, that too could be a reaction to the country’s kibbutznik past, though if we are to accept Seaton’s logic, it could also stem from a desire to shrug off any feeling of responsibility for the condition of the Palestinians.

And what about China? Wikipedia has no Chinese-language version, so that metric is unavailable. But Rand’s seminal novel The Fountainhead has been officially available since 2005 (there may have been samizdat versions before that), and some of her other writings since even earlier. It stands to reason that in the country where individual entrepreneurship has flourished in the shadow of an overweening state, her theories ought to be very popular indeed.