Read Cynthia’s response to reader questions about this article.

Silicon Valley has long suffered the reputation of being unwelcoming to women, from brogrammer attitudes to sexist apps to gender inclusivity, but whatever problems women may have with the tech industry, wage discrimination isn’t necessarily one of them. New research shows that there is no statistically significant difference in earnings between male and female engineers who have the same credentials and make the same choices regarding their career.

A recent study by the American Association of University Women titled “Graduating to a Pay Gap: The Earnings of Women and Men One Year after College Graduation“ (pdf) examined data on approximately 15,000 graduates to estimate the effect of gender on wages. Their sample was restricted to those under 35 years old receiving a first bachelor’s degree, in order to avoid confounding factors which affect labor market outcomes. Regression analysis was used to estimate wage differences, after controlling for the following choices and characteristics: graduates’ occupation, economic sector, hours worked, employment status (having multiple jobs as opposed to one full-time job), months unemployed since graduation, grade point average, undergraduate major, kind of institution attended, age, geographical region, and marital status.

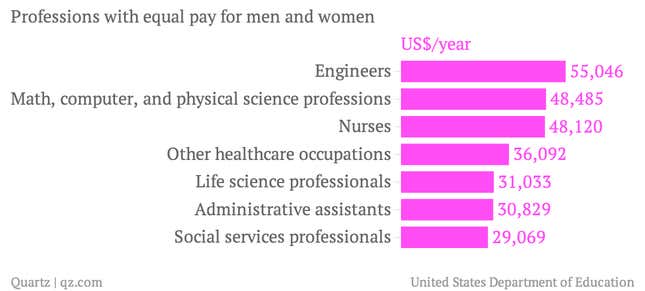

“Our analysis shows that occupations like nursing; engineering; and math, computer, and physical science occupations are the best-paying jobs for women one year out of college,” the authors Christianne Corbett and Catherine Hill report. “These tend to be occupations that are well paying throughout a career as well.”

According to the study, there are seven professions with pay equity (see below). When controlled for all factors other than gender, the earnings difference between men and women is about 6.6%, something most people don’t know. The casual observer often has an exaggerated view of the gender wage gap since occupational choices aren’t reflected in the statistics that are cited when the topic of wage equality is discussed in the media.

Since men and women tend to choose different professions, occupational segregation explains some of the difference in the gender pay gap since men are more likely to choose higher-paying fields. This results in women being disproportionately represented in lower-paying jobs. So men may enjoy an earnings advantage, but it doesn’t mean that women are being paid less for the same job.

The most common explanation for lower wages in female-dominated fields is occupational crowding. Women may be crowded into some occupations, either due to a preference against, or a barrier to, entering a STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) field. As more women enter a particular field, the pool of candidates becomes larger. Employers are able to pay lower wages and still attract employees who meet the job qualifications. Over time, we see wages decline in fields that have many applicants and an increase in wages in fields that have few applicants.

There is a negative correlation between the share of women in an occupation and the occupation’s average wage, but it is almost always impossible to draw any causal conclusion from a simple statistical correlation. We can take nursing as an example of an occupation that is highly paid even though most of the workers are female.

I asked University of Chicago Professor of Behavioral Science and Economics Dr. Richard Thaler if he thought social pressures influenced women in choosing lower-paying, predominantly female occupations. “Historically, that was certainly true,” said Thaler, the co-author of the 2008 best-seller Nudge, which discusses the frameworks and biases that shape decision-making, “but my impression is that it is no longer the primary factor. I think that young women are certainly encouraged to take up traditional male fields much more now than in the past.”

And he’s definitely right, particularly at the best universities in the United States. The 2013 entering class of Massachusetts Institute of Technology, which offers only a Bachelor of Science as an undergraduate degree, is 45% female, compared to 5% in 1966. Last spring, there were more women than men in the Introductory to Computer Science course at the University of California at Berkeley, which TechCrunch describes as a “feeder school to Silicon Valley’s top companies.”

In his 2014 State of the Union Address, President Obama said it was “wrong” and “an embarrassment” that women are paid 77 cents for every dollar a man makes, implying that the pay disparity is due to sexism and gender wage discrimination. His careful construction elides the fact that the 77% statistic does not refer to “equal work.” That number is a Census Bureau comparison of the annual wages of all workers, regardless of occupation.

The United States Bureau of Labor Statistics show that when measured hourly, not annually, the pay gap between men and women is 14% not 23%. The Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis prefers working with hourly wages, arguing “an incomplete picture” is cast with weekly earnings because women work fewer hours than men, “which would make a gap in weekly earnings between the two groups substantial even if their hourly wages are the same.” The BLS does have earnings data segregated by occupation and gender, but this is only a comparison of the same type of job. It doesn’t compare wages for equal work in the exact same job, a distinction which is made even clearer when we are gently reminded, “It is important to note that the comparisons of earnings in this report are on a broad level and do not control for many factors that can be significant in explaining earnings differences.”

College majors also play a large role in predicting future wages. Yet even when men and women choose the same major, graduate from similar types of colleges and receive similar grades, women still earn less than men but female engineering graduates earn 88% of what male engineering graduates earn ($48,493 for women compared to $55,142 for men). So, what we are seeing is that there are some women who get engineering degrees but then don’t become engineers. I studied computer science in high school and math in college but I’m neither a computer scientist nor a mathematician. Instead, I decided to make life choices that were more personally and spiritually rewarding: I was a rainforest conservationist in Brazil and a teacher in India.

One reason that explains why there is a pay gap when measured by college major but not when measured by profession is that some female engineers abandon their careers months after starting. This would explain why overall annual incomes measured one year after graduation would be lower for these women. If employers are risk averse, wages offered will be lower where productivity is less easily predicted (and where lower productivity is already revealed). The issue in this case is not gender differences in productivity but, rather, how employers predict what kind of worker they’re hiring based on his or her previous employment history.

Also, some women don’t go into the careers their college degree prepares them for because they have less attachment to the labor market. Men and women who have intermittent labor force participation have lower earning paths for several reasons: their current skills depreciate, they don’t receive on-the-job training, and they don’t build up seniority.

Another possible explanation for the lower earnings of highly educated women is that some women may not feel college is about building skills, but see it instead as an opportunity to demonstrate their value through signaling. Signaling in labor markets allows for employees to reliably communicate unobservable qualities to prospective employers in order differentiate themselves and gain a higher wage. The theory is that education can distinguish between a higher quality candidate and a lower quality one since the costs of education (time, money, effort) will be lower for the former.

Corbett and Hill don’t have data on women who work 30 to 40 hours per week (only 40 or more) but the BLS weekly earnings report showed that women who work 30 to 39 hours per week make 111% of what men make (see table 5). It’s possible that women who are more educated are able to work fewer hours because they have higher-earning partners.

The magnitude and interpretation of the relationship between gender and wages remain in dispute. After adjusting for all the known factors, Corbett and Hill’s model showed an “unexplained” 6.6% difference in wages between men and women who are full-time workers. Conflicting data from the BLS shows that some women who work full-time have a wage premium, and earn 11% more than men. The tech industry is unique in its history of being “equal pay for equal work”: A longitudinal study of female engineers in the 1980s showed a wage penalty of “essentially zero” for younger cohorts and today, the two highest paying professions with wage equality are in technology (computer scientist and engineer).

Despite strong evidence suggesting gender pay equality, there is still a general perception that women earn less than men do, and this perception is just one more factor discouraging women from entering the tech space.

Follow Cynthia on Twitter @NinjaEconomics. We welcome your comments at ideas@qz.com.

Correction: An earlier version of this story referenced table 4 instead of table 5 in the BLS weekly earnings report.