Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway failed to beat its target … again.

The legendary American investor has long spotlighted per share book value—assets minus liabilities—as the preferred performance metric of his giant holding company. He benchmarks Berkshire’s performance against the total return of the S&P 500 index, which includes dividend payments.

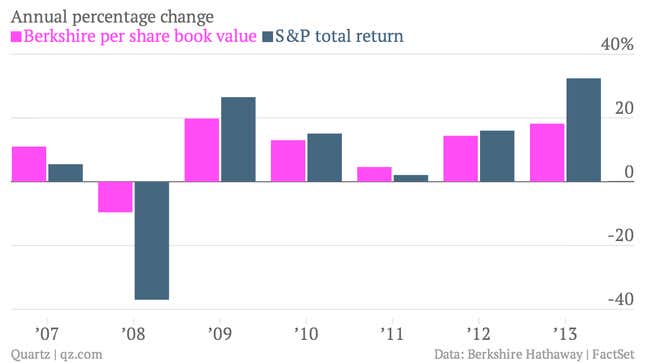

Berkshire had a good year, with book value per share rising 18.2%, according to Berkshire’s shareholder letter released yesterday. But the surge in the US stock market meant that the company’s performance fell short of the 32.4% rise in the S&P. In fact, the book value of Berkshire has failed to beat the S&P in four out of the last five years.

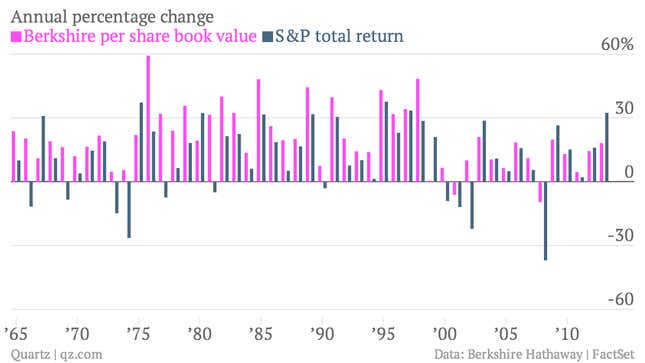

Usually, Buffett has suggested tracking how Berkshire does over longer market cycles, usually using five years as a rough guide post. That makes sense. Value investors such as Buffett—who try to buy assets on the cheap and hold them for the long term—can underperform the market for long periods of time, especially in periods when stock markets are logging big annual gains.

But Buffett actually shifted the goal posts slightly this year, suggesting shareholders consider Berkshire’s performance since 2007, rather than the five-year window he’s previously suggested to use when assessing performance. In his letter to shareholders, he writes:

Over the stock market cycle between year-ends 2007 and 2013, we over-performed the S&P. Through full cycles in future years, we expect to do that again. If we fail to do so, we will not have earned our pay. After all, you could always own an index fund and be assured of S&P results.

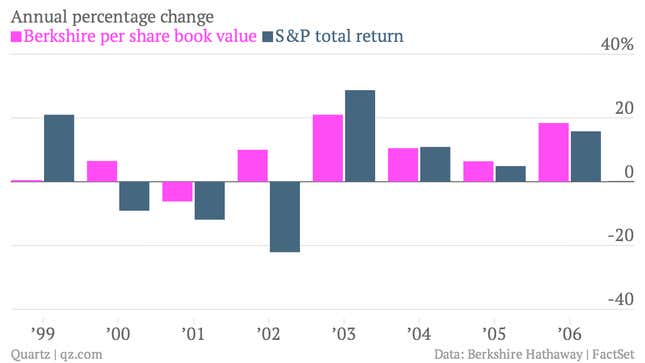

Should difficulty beating the market over the last five years be worrying? Probably not. There’ve been other periods when Berkshire has underperformed. Buffett famously sat out the technology stock boom of the late 1990s, resulting in Berkshire’s worst-ever relative performance in 1999. In January 2000, the Wall Street Journal’s Jason Zweig asked Buffett if he worried that perhaps the commentators calling him a dinosaur might be right.

“I know what will happen,” Mr. Buffett replied with implacable calm. “I just don’t know when.”

He was right. And when broad US stock markets tumbled in the early 2000s, Berkshire was in a much better position to weather the storm.

Berkshire typically tends to hold up exceptionally well when the broader stock market tanks suddenly, wiping out tons of shareholder wealth. Indeed, the conglomerate has only suffered two episodes of outright declines in book-value-per share in 2001 and 2008.

And Berkshire has fared far better during the ugliest episodes the stock market faced in recent years. For example, it only declined 9.6%—in book value terms—in 2008, when the S&P was down 37%.

It’s difficult to build long-term wealth if your portfolio collapses by 40% every few years. And to a large extent, avoiding such losses is the whole idea of the kind of “value investing” that Buffett and Berkshire Hathaway specialize in.

For the record, the S&P has only outperformed Berkshire 10 times since 1965, when Buffett’s previous investment vehicle acquired control of Berkshire Hathaway.

In other words, Berkshire Hathaway is an insurance company. Its real value to shareholders emerges when market disasters strike.