Strongly worded statements, threats of travel restrictions, and summit no-shows. So far, these are the relatively mild diplomatic implications for Russia of its incursion into Ukraine, as few in the West can stomach an open military confrontation with Moscow over its apparent occupation of Crimea.

But the markets are punishing Russia much more swiftly than the diplomats. A wide range of Russian assets—stocks, bonds, and the ruble—plunged in value today. To shore up the ruble, which is plumbing record depths, Russia’s central bank unexpectedly hiked interest rates today. It ratcheted up the benchmark one-week rate from 5.5% to 7%, and traders report that the central bank has also been spending billions of dollars in currency markets to stem the fall in the value of the ruble.

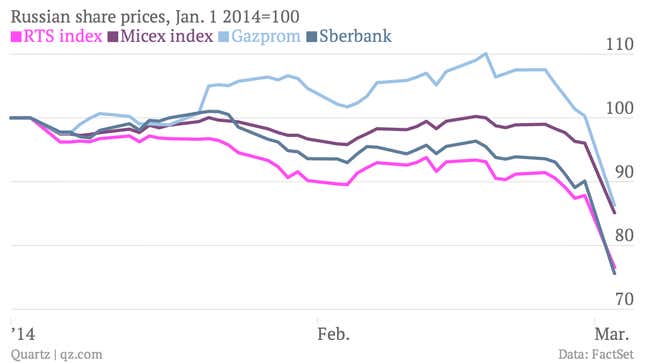

The two main Moscow stock markets, the Micex and the RTS, have fallen by more than 10% at the time of writing, in a broad-based selloff. Big Russian companies like Gazprom and Sberbank saw their share prices plunge as traders dumped their shares.

For its part, Gazprom said today that it would reconsider the gas price discount it extended to Ukraine only a few months ago. Of course, Russia has not hesitated to punish Ukraine by restricting its energy supply in the past, with reverberations felt throughout Western Europe. These trade links—Western Europe gets about a quarter of its natural gas from Gazprom—make strict economic sanctions against Russia, like the ones imposed by the West on Iran or Syria, impractical. After all, the international opprobrium that met Russia’s invasion of Georgia in 2008 was never backed with serious action.

As we have written before, Putin takes great pleasure in ”delivering a bloody nose” to his perceived enemies, even when it risks harming his standing on the international stage. Indeed, after speaking with Putin yesterday, German chancellor Angela Merkel reportedly told US president Barack Obama that the Russian leader seemed out of touch with reality—”in another world.”

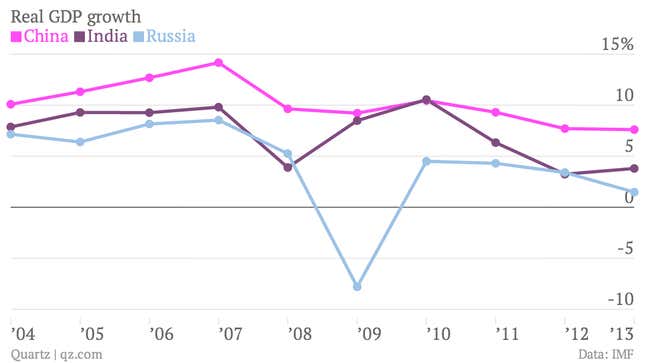

Economically speaking, the reality for Russia is not nearly as robust as the image projected by its officials’ belligerent rhetoric or its fast-moving military. Its growth has lagged emerging-market rivals like China and India for some time.

What’s more, Russia only recently vanquished double-digit inflation. An extended fall in the value of the ruble could push inflation back up, further denting the country’s economic prospects.

And so, perhaps for the first time since unrest broke out in Ukraine, Putin may be finding that his actions have costs—not the costs that world leaders threaten to impose in vague communiqués, but the pain that results from thousands of nameless, faceless transactions in stock, bond, and currency markets as investors flee the uncertainty and instability sown by Moscow’s unpredictable intentions in Ukraine. These are attacks that cannot be repelled by troops and tanks, but the damage they cause is every bit as real.