Once you scroll past the West’s soft suggested responses to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine—revocation of membership in the G-8, finger-wagging, village shunning and so on—there are only a few bracing proposals left. They dispense with civility and aim for the jugular. The three below stand out. If short of time, go immediately to the last, which would strike Russian president Vladimir Putin at his Achilles’ heel—oil.

Make Russians vacation in Pyongyang or Damascus

Although Russians have by and large been unfazed by his imprisoning and beating of protesters, oligarchs and pop singers, the one action that Putin has never risked is preventing his people from traveling or moving their money abroad. But “if you tell them, ‘You can no longer come [to the West] and you have to freeze in Moscow,’ then they will turn on Putin,” says former Georgian president Mikheil Saakashvili, whose country was invaded by Putin in 2008. He suggests an across-the-board rejection (paywall) of visas for Russian citizens to Western countries and anywhere else that wishes to go along. Putin’s circle could still travel. It was a balmy 72°F (22°C) in Damascus today, for instance.

Put Ukraine under the NATO umbrella

The pattern repeats itself—Putin goes rogue and the West responds with a late, light touch. Now he has claimed the right to military action anywhere in Ukraine. A seizure of the whole of industrialized eastern Ukraine seems far-fetched. On the other hand, the chances that he would invade Crimea were largely dismissed (including by Quartz), and it would be folly to apply western logic to his actions now. Thus, says Andrew Kuchins, from the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, DC, the threat to Putin has to be war. “We have to make absolutely clear—and in the most credible way possible—that Russian military intervention in other regions of Ukraine is a red line that will mean war with Ukrainian and NATO military forces if it is crossed,” Kuchins wrote at CNN.

Is the extension of the NATO umbrella (temporary rights as opposed to permanent membership) realistic when World War III could be the outcome? Charles King, a professor at Georgetown University, thinks not. “NATO cannot possibly extend security guarantees to a government that does not control its own territory,” King writes at the New York Times. But, while a substantial gamble, it may be the only way to get Putin to stand down.

And Kuchins argues that it is a smaller risk than people fear. “Putin is, after all, a calculating opportunist who will take advantage of weakness where he sees it. He is extremely unlikely, therefore, to risk war if he clearly understands the cost of crossing a real red line. The question is whether he has any belief that the United States and its allies will step up.”

Drive down oil prices

As of now, Putin is profiting from his invasion. That is because oil prices are up on the risk of a supply disruption. This enriches the Russian state budget, half of which is supported from oil and gas exports. But economist Philip Verleger notes that prices can go down as well as up, and he recommends inflicting pain by engineering the former.

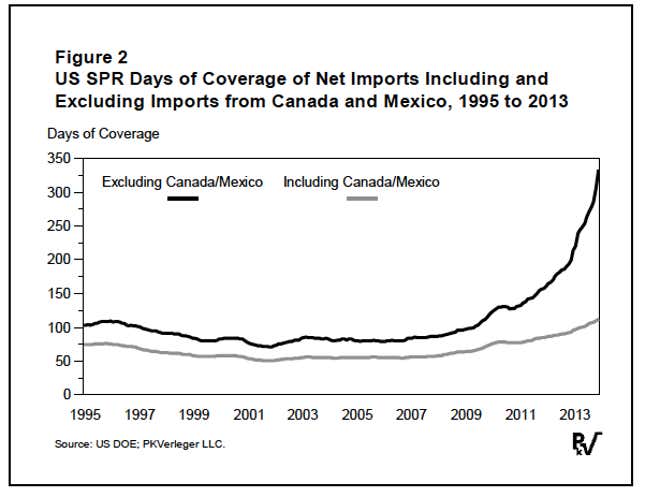

The tool is the US Strategic Petroleum Reserve, the 700-million-barrel underground cache of crude oil waiting in Texas and Louisiana for a rainy day (see chart below). In an overnight note to clients, Verleger argues that if the US were to ship just 500,000 barrels a day of oil onto the market, it would drive down prices by about $10 a barrel and cost Russia about $40 billion in annual sales. The US could keep doing this for years, he says. “[Russia’s] GDP might drop 4%, which would certainly count as a ‘consequence,’” he says. Half would come from lower oil prices and half from gas sales, whose prices Russia indexes to oil.

Verleger notes that Saudi Arabia, the current market-maker, would have to go along with the strategy and not cut back production. But he thinks that, given Putin’s detested support of Syrian leader Bashar al-Assad, the Saudis would likely agree.

The idea has history behind it. In 1985, Saudi Arabia decided to pump a lot more oil and increase its share of global oil sales. As a result, oil prices plunged by more than half, at one point in 1986 reaching $13 a barrel. The primary, unintended victim was the Soviet Union. “The Soviet Union lost approximately $20 billion per year, money without which the country simply could not survive,” wrote former Russian prime minister Yegor Gaidar. The economy went into a tailspin, as then did the politics, and in 1991, the Soviet Union was no more.

Which makes oil the most fearsome weapon of all.